The following is excerpted and adapted from an article that first appeared in the Journal of Homosexuality, Volume 49, Number 1, 2005.

SINCE THE MID-1700’s, personal ads have served as a way for lonely individuals of all persuasions to find love, friendship and just about everything in-between. While the primary appeal of personal ads has not changed significantly since then, the ads and the context in which they are placed have been dramatically affected by cultural and technological shifts. Most recently the Internet has fundamentally changed the way in which thousands of individuals use personal ads. No longer the sole domain of newspapers and other print media, personals have gone high-tech and become a dynamic, interactive on-line experience. More than simply transferring print ads to digital form, Web personals allow for more descriptive profiles, searchable global databases, hyperlinks to personal websites, and even the opportunity for immediate contact with personal advertisers. As an inherently global medium, the Web has also allowed for personals to be browsed far beyond any established circulation boundaries.

Homosexuals, not surprisingly, have always been a demographic group known to patronize the personals. Born and raised in isolation from other homosexuals, gays and lesbians who find it difficult to meet like-minded individuals through their established social networks have found personal ads to be an effective and relatively anonymous way to meet others for love and friendship outside of an urban gay ghetto. On-line, where gays and lesbians are known to comprise a disproportionate number of Web surfers, the utility of personal ads becomes even more relevant. Gays and lesbians unable (or simply afraid) to pick up a local gay newspaper or national gay glossy magazine, and unwilling or unable to pay high fees to participate in a telepersonal or video dating service can, from the comfort of their homes, browse personal ads from around the world anonymously and cheaply.

This article studies the use of on-line personal advertisements on the GLBT global Web portal PlanetOut. A random sample of advertisements from ten separate geographical areas is analyzed in terms of basic demographics, relationship goals, and self-presentation styles in order to reach conclusions about gays and lesbians and their use of global gay space for social interaction. These findings are complemented by responses from survey questions sent to those advertisers included in the sample.

In order to understand gay and lesbian personals on the PlanetOut website, however, it is necessary to take a closer look at the context in which the personals are placed. More than simply ways to meet others, personal ads challenge many notions of how the Internet proves useful to gays and lesbians. As one of the more practical and goal-directed forms of Computer Mediated Communication (CMC), personal ads provide a fairly systematic way of analyzing how individuals use new media technologies. Of interest here, in particular, is to what extent gays and lesbians maintain local identities when taking advantage of the tools offered in virtual communities.

Tom Rielly, who founded the nonprofit group Digital Queers and later the for-profit PlanetOut, described his hopes for the initial Digital Queers website in this way: “Our vision is a national electronic town square that people can access from the privacy of their closet—from any small town, any suburb, any reservation in America. It’s like bringing Christopher Street or the Castro to them.”* The idea of linking together gays and lesbians outside of urban areas into one global gay and lesbian community had never seemed possible prior to the Internet. With the ability of the Internet to target gays and lesbians, however, it should come as little surprise that even early in its development, the Internet was seen as a way to “broadcast” to otherwise isolated gays and lesbians. After all, while there’s been a handful of national gay and lesbian magazines and occasional syndicated radio and television programs aimed at gay and lesbian audiences, most news and information specifically relevant to gays and lesbians were found in local gay newspapers.

The Internet provided a way for media created by and for gays and lesbians to have potentially unlimited circulation in an essentially anonymous context. This potential to reach thousands of closeted gays and lesbians did not go unnoticed by Internet industry executives. David Eisner, a vice president of America Online, remarked: “The gay and lesbian community was one of the first to take advantage of the anonymity on-line. From the beginning up until now, the community has been an early adaptor of all the functionality available” (San Francisco Chronicle, 6/23/00).

While many early virtual communities had no roots in the real world, having coalesced exclusively on-line, Web portals like PlanetOut have not only built an on-line space around an existing real-world demographic, they continually try to reach that off-line audience in an attempt to lure them on-line. PlanetOut, for example, uses one-third of its advertising budget to sponsor “community events” in off-line gay and lesbian neighborhoods (Advertising Age, 6/19/00). PlanetOut not only co-sponsored the Millennium March on Washington, but it webcast the real-world event of 200,000 participants to an on-line audience of over half a million (Edmunton Sun, 5/3/00). Far from being exclusively a “virtual” community, PlanetOut also frequently sponsors nights at local gay and lesbian bars where members, who may know each other from chat rooms or personal ads, are encouraged to get together in the flesh. There is clearly less a distinction between “real” and “virtual” when it comes to spaces such as PlanetOut. More than creating a virtual reality, PlanetOut seems to focus more on fostering existing real world ones.

PlanetOut has certainly not been immune from sometimes hostile criticism that, more than providing an on-line forum for the gay and lesbian community, it is actively shaping the nature, direction, and perception of that community. In March of 2000, PlanetOut first announced that it planned to purchase Liberation Publications Inc., which publishes Out and The Advocate, the two largest gay and lesbian print magazines, and in November it began a merger with On-line Partners Inc., which operates Gay.com. Although the PlanetOut/Liberation Publications deal fell through one year after it was first announced,* reportedly due to the sudden downturn of Internet company stock valuations (on which the deal was primarily based), criticism of the emerging gay media behemoth has not abated.

Reaching over 3.5 million unique users every month, PlanetOut Partners—the name of the parent company that now operates two distinct web portals, Gay.com and PlanetOut—has been described as a “dangerous monopoly among gay media” by former Out president Henry Scott (Los Angeles Times, 4/11/01). Scott went so far as to urge leaders in the gay and lesbian community to press for a federal anti-trust investigation. That, however, is a very unlikely prospect considering that PlanetOut still reaches only a tiny fraction of the total estimated gay and lesbian population, despite the fact that it reaches far more individuals than any other form of GLBT-oriented media. While not at all an anomaly in the “new economy” of Internet companies, even a quick look at the ledgers makes arguing against any suspected monopoly of queer media difficult. Ironically enough, one of the most contested—and closely watched—outcomes of this rapid consolidation of gay and lesbian media outlets was whether previously free services such as personals and chat rooms would become a source of revenue for the company. As explained in the LA Times (4/11/01), “Even [Henry] Scott concedes that the greatest strength of the two sites was never their reportage or commentary; it was, and is, their personal ads.”

PlanetOut personals are, in fact, the most heavily trafficked portion of the entire portal. PlanetOut launched its Personals service in 1999, and today reports over 250,000 ads in its database (Philadelphia Inquirer, 4/20/01). According to Megan Smith, as quoted in an August 1999 PlanetOut press release: “Gays and lesbians have gone on-line to reduce isolation and fear for several years now, so they are early adopters of the Internet as a way to find and connect with other members of the community. Whether they are living in San Francisco or the middle of Montana, PlanetOut’s Personals channel gives members a privacy-sensitive environment in which to build community.” The personal ads, in Smith’s view at least, serve a dual function of building community across global boundaries as well as assisting with far more local concerns. In many ways, the personals on PlanetOut represents the nexus between the two competing definitions of community discussed above: they can build community both on line and off. Furthermore, the traffic generated by 250,000 searchable ads highlights the importance of community within an industry context. PlanetOut is interested in personal ads insofar as they create more registered users and therefore not only a “community,” but a community that can be sold to advertisers.

Findings

PlanetOut personals simultaneously serve as a local and global advertisement in a manner unlike its “lonely hearts” predecessors. Although almost all of the survey respondents reported searching for ads based primarily on zip code, the ads can still be searched by a global audience. PlanetOut, in fact, promotes the fact that their database of over 250,000 personals draws from a worldwide gay and lesbian population. The personals home page regularly displays four “featured ads” from different parts of the country (and occasionally the world), while portal pages such as “Fantasy Man Island” and “Lesbian Love Boat” also highlight ads that users might never be exposed to if they limit their searches solely by geography. The various features that transport people from their home zip code and thrust them into the common space of the global portal provide a stimulus for the virtual gay and lesbian community that PlanetOut promotes; but it is important to remember that the personal ads are used by the portal in a far more strategic way. More than just a service utilized by PlanetOut members, the Personals channel also provides a significant amount of free and original content for the portal itself.

Despite the emphasis on building a national GLBT community, our analysis of ads drawn for this study clearly indicates that the PlanetOut community is not a unified one that enjoys a consensus among its users. In fact, apart from gender, geography is the most powerful factor differentiating ad content. In terms of the most basic variables, such as self-identification as gay or lesbian, clear patterns emerge that separate small towns from large cities.

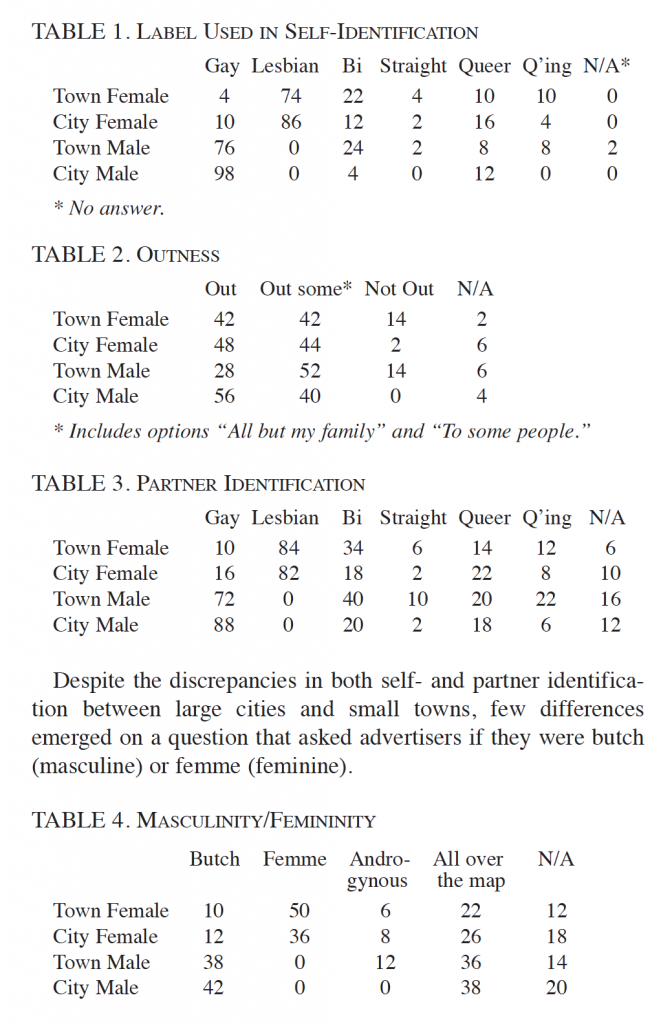

In general, men and women from large cities were more likely to identify as gay or lesbian than those from small towns (Table 1). Large city advertisers were also more likely to adopt the politically potent label “queer” that has perhaps not yet gained currency in smaller communities. Conversely, small-town advertisers, both men and women, were more likely to identify as bisexual, straight, or questioning than large city advertisers. About fifteen percent of the advertisers in small towns were “not at all” out, a much higher figure than in cities. Men in small towns were less likely to reveal their HIV status.

It should be noted that the mean age for both men and women was lower in small towns than in big cities. (The average age for females was 30.8 years in big cities and 28.6 years in small towns. The average for males was 32.8 and 28.3, respectively.)

The anonymous nature of on-line soliciting for these small town residents provides a discreet option to meet someone of the same sex without walking into any public spaces such as a gay bar or bookstore—if such clearly marked gay and lesbian spaces are even locally available. In fact, numerous ads from small towns placed by individuals who are not forthcoming with their sexual orientation specifically mention the need for respondents to be discreet: “I’m looking for someone clean, honest and into the same discreet fun I seek with no strings attached also this person should be some what attractive and between the ages of 19 and 30 I myself am 34 but can easily pass for 25 and have the mind set of an 18 yr old” (small-town male).

Virtually all of those self-identifying as “straight” or “questioning” were from small towns. Interestingly enough, though, these individuals were no less likely to use the service to find sex or a relationship (as opposed to solely a friendship) as their gay- or lesbian-identified counterparts. In general, both men and women in small towns were more likely than city users to be seeking someone who identifies as bisexual, straight, or questioning (Table 3). Most straight, bisexual or questioning persons were seeking someone who identified in the same manner. Though gay- and lesbian-identified individuals were willing to consider someone who identified as bisexual or straight, the small town non-gay individuals rarely returned the offer.

Perhaps the most notable finding here is not that women in small towns tend to identify with what is historically expected of their sex (that is, feminine), but that both men and women in large cities were less likely to answer this question at all. Like other labels that may have more resonance in larger cities, such as “queer,” the terms “butch” and “femme” may be more potent within the gay ghettos than they are in the suburbs. It is plausible, for example, that while “androgynous” might indicate a certain type of transgendered status for males in large cities, it’s more of a middle-of-the-road descriptor for some men in small towns (where twelve percent identified as such). Masculinity was also a concern in free-form sections where, particularly in small towns, many men were seeking “other straight acting” or “masculine” partners while shunning “femme” types.

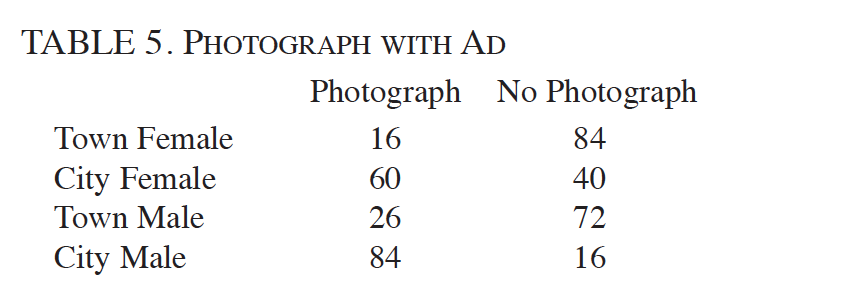

Many of these trends are intuitive in that they reflect the freedom of urban areas and the constraint of smaller towns in terms of sexual expression. As a final example, consider the number of men and women who choose to post a photograph along with their personal ad. In small towns, without the same level of anonymity provided by a large city, both men and women are less likely to post a photograph with their ad (Table 5). Not only are women significantly less likely to post a photograph than are men, but both men and women in small towns are significantly less likely to post a photograph than their urban counterparts.

Those survey respondents who did post a photograph overwhelmingly said that they did so in order to increase the number of potential partners who saw their ad and would be inclined to respond. One such example: “Personally, I believe there is a heightened level of interest when a picture is posted. I’m sure most people agree that when dealing with the anonymity of the Internet, despite the web site’s [PlanetOut] attempt to probe into the advertisers personality with certain questions, most decisions to respond are based on physical attraction” (large city male).

Others noted that posting a photograph facilitates the process of meeting someone new by eliminating in advance any potentially awkward meetings when a respondent might be surprised by an advertiser’s appearance: “I felt that since I wouldn’t be particularly interested in a ‘blind date,’ I should be willing to take that first step and put my picture out there. It also takes one of the ‘mating dance’ steps out of the picture” (large city male).

Most survey respondents who did not post a photograph reported largely technical reasons for not posting a photo (no scanned pictures, inappropriate GIF sizes). Others, however, did cite privacy as well as more moral objections: “I did not post a photograph because I felt that people will base their opinion of you on a photo before they get a chance to learn more about the person” (small town female).

Not posting a photo does not necessarily equate to entirely removing the advertiser’s body from the ad. Many ads, notably those of small town males, compensated for a lack of direct visual representation by spending a great deal of time describing and classifying their physical attributes.

Local Versus Global “Community”

PlanetOut presents a cosmopolitan view of GLBT culture that not all members of the on-line world choose to adopt as their own. For instance, few small town gays and lesbians are looking for someone to induct them into the more recognizable urban gay scene. Instead, they are largely looking for others not unlike themselves, who are content living outside of the very urban sensibility that PlanetOut tirelessly tries to package and sell. By interacting only with other advertisers in their geographical area, these users are able to put a local spin on the global forum. They take what they need from the self-described on-line community, namely the functionality of the personals, but disregard much of the portal’s rhetoric. In short, despite the homogenizing on-line community of PlanetOut that exists without regard to spatial or temporal boundaries, individual users are still clearly aware of their physical location when interacting on-line.

Users logging on do not necessarily enter into alternate spaces where they play with shifting, multiple identities. In fact, it appears that within a space such as the PlanetOut portal, where identities are tenuous, local identities become even more solidified. While “identity play” and multiple identities have been hailed as the hallmarks of on-line communication, most personal ads do their best to clarify, through questionnaires and profiles, the very identities that are thought to be fluid. This is not to say that advertisers cannot be dishonest in their profiles, post multiple ads assuming various identities, rely on hyperbole, or re-position their profiles regularly. While this sort of identity play surely happens in a limited number of cases, the fact is that on-line profiles serve a very practical and tangible goal—namely the potential to meet someone for friendship or relationship. Posting a fictitious identity would ultimately be self-defeating. (Of course, fictitious identities might be more useful on other channels such as chat rooms, where people are often not looking for a real-world relationship at all.)

On-line personal advertisements are a dynamic feature that provides new levels of anonymity, speed, and interactivity. Gay men and lesbians have not only been early adopters of new technologies such as the digital versions of personal ads, but one of the demographic groups that have most fully exploited the capabilities of the on-line medium.

The interaction of gay and lesbian communities on-line and off-line is a particularly interesting and even a slippery one. On-line communities have also been widely discussed as imagined places where communities of interest and little else have emerged hoping to create some Gemeinschaft of social interaction. The Web, moreover, with its ability to transgress spatial and temporal boundaries and provide anonymity, safety, and fluidity, has been situated as an inherently hospitable medium for GLBT people. That gays and lesbians have taken to the Web in large numbers to find friendship and romance should not seem surprising. However, through survey responses and analysis of 200 personal ads, most users of PlanetOut’s Personals feature indicated that they were not necessarily looking for the global gay community.

Instead, most advertisers maintained their local identities even while immersed in the nominally global space offered by PlanetOut. Advertisers were interested in interacting locally, eager to move from on-line to off-line communication, oftentimes not overly concerned with maintaining anonymity, and not terribly interested in toying with multiple identities. Most notably, despite claims by PlanetOut of providing an “on-line community for gays and lesbians,” most users on the Personals Channel did not consider themselves a part of this virtual community even when they did recognize the existence of a local, geographically-based gay and lesbian community.

David Gudelunas, PhD, is affiliated with the Annenberg School for Communication, University of Pennsylvania.