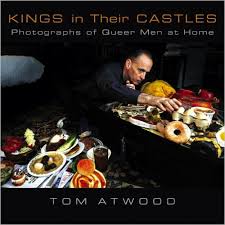

Kings in Their Castles: Photographs

Kings in Their Castles: Photographs

of Queer Men at Home

by Tom Atwood

University of Wisconsin Press. 92 pages, $35.

This collective portrait of gay urban artists, writers, musicians, and designers suggests that gay men are actually more interesting with their clothes on—an invigorating perspective, especially considering that bookstore shelves are practically buckling under the weight of gay-themed photo collections whose focus is the sculpted, semi-nude male form. Atwood’s photographs are portals into the everyday existence of gay men within their own carefully constructed spaces: their homes. Whether it’s writer Michael Cunningham biting his nails, deep in conversational thought, artist Ross Bleckner yawning in his studio, or DJ Junior Vasquez contemplating garbage on his rooftop, Atwood documents the rare, capricious moments that can make his famous subjects seem familiar and accessible. In the collection’s Foreword, author Charles Kaiser (Gay Metropolis) acknowledges that Atwood, at times, “arranges” his subjects, as with the photo of filmmaker John Waters packing fake food in a suitcase, but that the point of his work is not to “imitate life, but to clarify it, by making it more vivid.” Shot primarily on 35 mm film with minimal cropping, the 71 portraits included here often show both floor and ceiling to give the viewer an overview of the environment. The technique challenges the eye without sacrificing balance, particularly in the shot of drag queen Hedda Lettuce—backed by her wall of wigs— fending off her dog as she’s about to leave for a performance. Atwood’s subjects rarely look at the camera, and yet even the portraits of lesser-known performers and artists shimmer with emotion and a kind of intimacy that is at once familiar and new.

Tony Peregrin

Casa Susanna

Casa Susanna

Edited by Michel Hurst and Robert Swope,

powerHouseBooks. 156 pages, $29.95

Sometimes, when libraries catalogue books about everyday life, they use the notation “Homes and Haunts.” I can’t think of a better way to categorize Casa Susanna, a fascinating photographic record of a transvestite community that gathered in the Catskill Mountains town of Hunter, New York, in the 1950’s and early 60’s, and a book that manages to be homey and haunting at the same time. The photographs, which Robert Swope recently uncovered at a flea market in New York City, are both familiar and strange. Some are predictable drag shots: as the residents of Casa Susanna camp for the camera, readers might agree with Swope that “these initial images, while amusing, basically bored me.” But what’s brilliant about the ladies of Casa Susanna is how they turned the mundane into the magnificent. Many of the photographs are, at first glance, indistinguishable from the fading mid-century snapshots that fill American attics: family dinners, slightly tipsy parties, the gathering in the kitchen of women of a certain age. They have a delicious kitsch appeal—plastic slipcovers and artificial Christmas trees, rhinestone glasses and scratchy nylon hose. There is a homey-ness here, one that was, as Swope points out, “a studied illusion.” Casa Susanna testifies to the enduring spirit of the people who gathered there against the odds, and reminds us that there was far more going on before Stonewall than we tend to think, even if much of it took place behind closed doors. Peeking into their world forty years ago is thrilling, but also a little disconcerting: without their full history, without the captions that would turn these photographs into living history, the world of Casa Susanna remains just out of reach, haunting us with the silence of snapshots discarded in flea market bins.

Christopher Capozzola