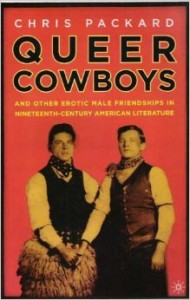

Queer Cowboys and Other Erotic Male Friendships in

Queer Cowboys and Other Erotic Male Friendships in

Nineteenth-Century American Literature

by Chris Packard

Palgrave. 144 pages, $55.

COWBOYS are queer—or at least they were in frontier tales of the 19th century. Such is the conclusion of Chris Packard’s new book on this topic. Packard develops his thesis through a reinterpretation of both classic and popular frontier literature. Avoiding the usual theoretical prose that accompanies most works of queer studies, Queer Cowboys embarks upon a historical literary journey that does more than simply expand our ideas about the 19th century. Rather, this slim volume illustrates how erotic male relationships were central qualities in the stories and tales that came to shape the myth of the frontier before 1900.

Our idea of 19th-century America often rests on two contradictory images:

Packard argues that the figure of the cowboy, both in life and in literature, is an odd character. “He doesn’t fit in,” writes Packard, “he resists community; he eschews lasting ties with women but embraces rock-solid bonds with same-sex partners; he practices same-sex desire.” The cowboys and other pioneers who populate the works of such writers as James Fenimore Cooper, Mark Twain, Bret Hart, and Owen Wister emerged within a social milieu in which male bonds were unburdened by contemporary stigmas of homosexuality. Queer Cowboys, then, endeavors to rehabilitate the homoerotic aspects of American Western literature. Writes Packard: “I hope to teach readers how to recognize homoerotic affection in a historical discourse that was free from derogatory” notions of male-male erotic friendship.

To accomplish this goal, Packard takes us from the woodlands of western New York to the saloons of Nevada, showing how the image of the West provided unfettered terrain for male writers to explore erotic bonds well beyond the demands of Victorian domesticity. For example, the friendship between Natty Bumppo and Chingachgook in Cooper’s classic The Deerslayer was an “interracial marriage,” while the poems of Walt Whitman infused our national identity with “manly love between comrades.” Western expansion for Whitman depended upon “temporary, intimate encounters between autonomous men.” Owen Wister’s wildly popular The Virginian, published in 1901, transformed the Western from a pulp genre to a more respectable form and established the codes of the Western that would govern this genre in film, radio, and print through much of the 20th century. Narrated by an Easterner who travels west and befriends a cowboy named the Virginian, the novel celebrates cowboy life and the intimacy of male bonding that such a life allows, even as it ridicules traditional marriage. “As much as The Virginian is about a cowboy giving up his occupation to marry the schoolmarm,” writes Packard, “it is also about the increasingly intimate friendship between the narrator and the Virginian.”

If Queer Cowboys has one flaw, it is that it offers us little about the lives of actual cowboys and pioneers. While the book does provide photographs and images of cowboys bonding around campsites and lodges, displaying a physical intimacy that was both normal and acceptable, it does not delve much into the historical record of the lives of such men. However, the book is not a social history but instead a literary analysis exploring the homoerotic themes that thread through the stories, poems, and songs of the 19th century. Like English schoolmasters who encouraged their students to ignore certain “profane” passages in Plato, we too have been taught to look past those queer moments that fill our literature, portraying heterosexual masculinity as the norm of pioneer culture. In reclaiming these themes, Queer Cowboys offers a useful revision to a central myth of American identity.

_____________________________________________________

James Polchin is a writer and a lecturer of writing at NYU.