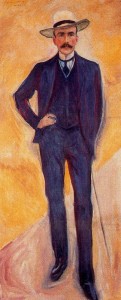

THERE’S an arresting portrait of Harry Count Kessler, painted by Edvard Munch in 1906, that hangs in the Nationalgalerie, Berlin. A handsome, mustached, fine-featured man looks at us from beneath a rakishly tilted white summer hat. Wearing a dark suit, leaning slightly on a stylish thin cane, Count Kessler is elegant and impeccable, and appears younger than his 38 years. His gaze is intelligent, quizzical, attractive, yet something about Kessler’s pose suggests the fastidious remoteness of a very private individual. Who was Kessler, once called by W. H. Auden “probably the most cosmopolitan man who ever lived”—and why should readers of this journal, in particular, cherish his memory?

Harry Count Kessler (1868–1937), perhaps now best known for his extraordinary diaries, was born in Paris to an Anglo-Irish mother, herself of mixed and exotic origins, whose striking beauty so entranced old Kaiser Wilhelm I that he ordered her husband, a wealthy German entrepreneur, to be given a title. Thus young Harry was born a Count, but he also inherited rumors he never entirely lived down suggesting he was the Kaiser’s illegitimate son. Educated first, and very unhappily, in French schools, then in England, where he was a contemporary of Winston Churchill at St. George’s, Kessler came to admire the ideal of the English gentleman. After two years in England, he was sent to the Johanneum in Hamburg, a school with a formidable tradition in classics, where Kessler was first introduced to the moonlit Romanticism of homoerotic Wilhelminian culture.

Kessler’s diary, begun at age twelve, records the time he met, at age eighteen or so on a seaside holiday, a pair of aristocratic homosexual lovers, who swore him to secrecy about their relationship. The couple shared the arch-conservatism, pantheistic mysticism, secret language and rituals that also characterized a circle of courtiers around the young Kaiser Wilhelm II, a group that was to be violently shaken by homosexual scandal. Same-sex relations among men had been criminalized in 1871 by the notorious Article 175 in the German penal code, and Oscar Wilde’s imprisonment in 1895 was intimidating to homosexuals everywhere. Kessler’s homosexuality, which he struggled throughout his life both to conceal and to justify, rendered him a “secret outsider” and made him more receptive to the avant-garde, to modernity altogether, than he might otherwise have been amid the stifling conformism of Imperial Germany’s social elite. Living at the pinnacle of German and international society, Kessler was always conscious of the need to exert great self-discipline, not to cause even a hint of scandal. His position was indeed analogous to that of the very few wealthy Jews who were accepted at Court, but always on sufferance, wary of the slightest misstep.

Even as a young man, Kessler was renowned for the bearing and refinement captured memorably by Edvard Munch. Sensitive, guarded behind a charm that repelled attempts at intimacy, Kessler was effortlessly polyglot. A voracious reader in Greek and Latin, French, English, and German, he was noted for his flawless command of these and other languages. He attended the universities of Bonn and Leipzig, read political economy and philosophy, and joined the most aristocratic fraternities, while avoiding their ritualized drinking and dueling. After a trip to New York, where he sparkled at Mrs. Astor’s parties as “a good dancer, and a Count!”, he went on to Egypt and Italy before reporting for military service in one of the most prestigious Imperial regiments. There Kessler had his first great love affair with a fellow cadet, Otto von Dungern, a nineteen-year old from a noble Bavarian family, slender, handsome, blond, and a brilliant equestrian. Kessler’s diary records many meetings with von Dungern, sharing travel and quarters during military maneuvers. Shortly after completing his military service, von Dungern proceeded to marry, an outcome that Kessler endured with several lovers. Kessler began to understand that he would ultimately be alone. The frenetic social whirl that he both craved and complained of was partial compensation for the lack of intimacy in his life.

Aspiring to make sleepy Weimar a cultural beacon as it had been in Goethe’s day, Kessler got himself appointed Director of the Grand-Ducal Museum for Arts and Crafts, only to be sabotaged by intriguing courtiers and the hostility of the philistine young Grand Duke, abetted by Kaiser Wilhelm II himself, who loathed all innovative art. Kessler was forced to resign because an exhibition of Rodin drawings, dedicated to the Grand Duke, included a squatting female nude presenting bare buttocks in a pose deemed insulting to royalty. Frustrated in his ambitions for Weimar, Kessler was already launched on that combination of connoisseurship, diplomacy, and sympathy for emerging creation that brought him into contact with the leading artists of his time, a galaxy of European talent for whom he functioned as Maecenas, intermediary, and sometimes personal friend. Shuttling between Weimar, Paris, London, and Berlin, Kessler knew and often visited the leading galleries of Europe, and eventually met established painters such as Monet, Renoir, and Degas, and younger artists including Signac, Vuillard, Bonnard, Rodin, and Maillol. He bought works from most of these and many other artists. Kessler also discovered and helped support developing German, English, and Scandinavian artists and writers: he was a cormorant collector of talent in all media, including the theatre. In addition to painters and sculptors, he corresponded and met with André Gide, Jean Cocteau, Albert Einstein, Marcel Proust, Virginia Woolf, George Bernard Shaw, Isadora Duncan, Josephine Baker, and many musicians. Kessler knew aristocrats, bankers, diplomats, and statesmen all across Europe: he was the indispensable unattached “extra man” at innumerable parties, confirming a gay role that has its analogue even today.

Unique among Kessler’s artist clients, the sculptor Aristide Maillol became close to Kessler, not least through Kessler’s relationship with Gaston Colin, the muscular young French cyclist who was one of Maillol’s models. After several years as Kessler’s lover, Colin also married, yet remained devoted to his sometime patron. Kessler’s generosity to a large number of artists was sustained by a substantial income, in the pre-war years, derived from his father’s international businesses. His patronage was not confined to the visual arts: he also funded the short-lived art and literary journal Pan; established the Cranach Press that ultimately produced, among other works, a sumptuous edition, illustrated by Maillol, of Virgil’s Eclogues; and supported the earliest efforts of Max Reinhardt in the theatre. Kessler suggested to Hugo von Hofmannsthal the central idea, and wrote the scenario that later became Der Rosenkavalier, and he later collaborated with Serge Diaghilev and Hofmannsthal on a ballet based on the biblical story of Joseph. Kessler seethed with creative ideas, forever the catalyst for new developments in the art world.

The First World War was suicide for Europe and a personal catastrophe for Kessler. Initially enthusiastic for the war, as were virtually all his contemporaries, Kessler rapidly became disillusioned as he saw his cosmopolitan world destroyed. His beloved sister, married to a French marquis, was cut off from him throughout the conflict, and so was his ailing mother, who died before he could visit her. Countless friends in England and France were likewise inaccessible, though Kessler managed to smuggle support to Gaston Colin and his family. Kessler served on the Eastern Front, experiencing in war-torn Galicia bitter combat—and another great love, with a young staff officer. Posted then to Verdun, he was witness to the worst horrors of the Western Front and was finally sent home, diagnosed with “shell shock.” Barely recovered, he was sent as a secret envoy to neutral Switzerland to explore possibilities for negotiated peace. In that mission he was undermined by envious career diplomats, and after Germany’s defeat he accepted the thankless assignment of establishing diplomatic relations with liberated Poland, but was compelled to resign after less than a month.

These and other disillusioning experiences transformed Kessler into a left-wing liberal, a pacifist, and an active defender of the Weimar Republic. He embarked on a political life, devoting more than a decade to ceaseless travel, writing, and speaking on behalf of pacifist and liberal organizations, trying to make the League of Nations effective, and undertaking diplomatic missions for the Foreign Ministry. In 1924 he campaigned unsuccessfully for the Democratic Party as candidate for a Reichstag seat. He was accused of betraying his own class, derided as “the Red Count,” threatened by right-wing conspirators, and snubbed by former comrades in arms and university fraternity brothers. The fortune he inherited was severely eroded by confiscations—the French and British governments considered him an enemy alien—and much of the rest destroyed by inflation. The crash of 1929 and the subsequent banking crisis completed his financial ruin; but Kessler, ever the aristocratic æsthete, was never good at economizing. He made ends meet by selling off his collections piece by beloved piece, re-financing his house in Weimar, and begging his sister for subventions. Kessler’s optimism and self-assurance, his hopes for Europe and the world, drained away in almost precise proportion to the loss of his fortune. And yet, throughout all these experiences, he continued to write, filling volume after red-leather volume in the minute hand that recorded with meticulous detail meetings, conversations, observations, and musings that, in sum, constitute a vast record, some 15,000 pages, of what happened last century in Germany and Europe. Only a fraction of the diaries has ever been published in any language, though there are plans to issue all of them eventually on cd-rom. A recent edition of a translation by Charles Kessler (no relation) contains some of the diaries from 1918 to 1937. Even this limited selection vividly evokes the events, personalities, and atmospheres of interwar Europe.

Inspecting the former Imperial Palace in Berlin looted by sailors during the uprising of December 1918, Kessler writes with anger: “But these private apartments, the furniture, the articles of everyday use … are so insipid and tasteless, so philistine, that it is difficult to feel much indignation against the pilferers. Only astonishment that the wretched, timid, unimaginative creatures who liked this trash, and frittered away their life in this precious palatial haven, amidst lackeys and sycophants, could ever make any impact on history.” Enrico Caruso, seen in Sorrento, “looks like Napoleon on St. Helena. Always gloomy and preoccupied.” Meeting Einstein at a bankers’ dinner party, Kessler asks him what problems he is working on, and receives the reply: “he said that he was engaged in thinking.” At a bull fight in Barcelona: “Loathsome memory, despite the colorful, savagely lively, grandiose spectacle. The slaughter of the helpless old horses, whose bowels are torn out of their bodies, is shocking and disgusting. … By the end I felt as though I had been bludgeoned, mentally apathetic and physically fit to vomit.” He describes Bertolt Brecht: “strikingly degenerate look, almost a criminal physiognomy, black hair and eyes, dark-skinned, a peculiarly suspicious expression.” Meeting Nijinsky again after the great dancer’s descent into madness, Kessler fails to recognize him until prompted by Diaghilev, then tries to encourage Nijinsky “with gentle words. The look he gave me from his great eyes was mindless but infinitely touching, like that of a sick animal.” Wilhelm II, always an object of Kessler’s contempt, is characterized as “this nincompoop and swaggerer who plunged Germany into misfortune. … Not a facet of him is capable of arousing pity or sympathy.” Lunching in 1928 in Vienna with Richard Strauss, he reports: “Strauss aired his quaint political views, about the need for a dictatorship, and so on, which nobody takes seriously.”

Reading the Kessler diaries, we feel ourselves eavesdroppers at a particularly grand party, and come to admire Kessler’s sheer stamina, his acute eye, his self-discipline. Throughout, we note his faith in art, in what Germans call Bildung, the conscious cultivation of learning and æsthetic culture. We also encounter some of Kessler’s views on sexuality and homosexuality, though few details of his intimate relationships. Recalling Greek antiquity, Kessler argues for a version of sexual liberation, of uninhibited sensuality, and imagines a society that is free of its “hypertrophy of shame,” which he attributes to the malign influence of modern women, the church, and venereal disease. In 1907, in the wake of the Moltke-Eulenburg scandal that harshly exposed the vulnerability of homosexuals, even royal friends, Kessler predicted that when public outrage dissipated there would be some benefit, if only because a once-impossible subject had been publicly aired: “Around 1920 we—which is not the case today—will hold the record in pederasty, like Sparta in Greece.” This prophecy was not far off the mark: the interwar Berlin of Isherwood and Auden, now known to us largely through versions of Cabaret, was notorious for sexual, including homosexual, freedom.

It was inevitable that Kessler should fall afoul of the Nazis, of whom he wrote: “it is difficult to say which feeling is stronger, loathing or pity, for these brainless, malevolent creatures.” In March 1933 he was told he was high on the Nazis’ black list, and urged by prominent friends to remain in France. Fleeing from France to Spain, then back again to France, battling illness and the unaccustomed necessity to write for a livelihood, Kessler never saw Germany again. His own valet revealed himself to be a Nazi agent, his house in Weimar and flat in Berlin were ransacked by the Gestapo, then plundered by creditors and others, but his multi-volume diary had already been hidden outside Germany. Count Kessler penned the last entry only a few days before he died in 1937. Missing volumes were recovered from a Majorca bank vault as recently as the 1980’s and deposited in the German National Literature Archive, Marbach, which safeguards the voluminous Kessler papers. If Kessler’s contributions to German public life were largely forgotten after his death in 1937, his achievements in the development of modern art, and above all his diaries, have assured his memory will endure.

Count Kessler was buried in the family tomb at Père Lachaise cemetery in Paris, after a funeral attended by a sparse assemblage, including none of the many artists he helped support. Kessler was compelled to witness and endure the destruction of cherished values and institutions, a whole fabric of culture and associations that had shaped and nourished him; but he was not a mere bystander. His struggles for political and human decency, his generosity and engagement, compel admiration. Disregarding personal dangers, Kessler displayed great courage, and the written record of his life continues to move and enlighten us. If his literary legacy seems secure, so too should be his place in gay history.

A. J. Sherman, a foundation trustee living in Vermont, is the author of Mandate Days: British Lives in Palestine, 1918–1948.