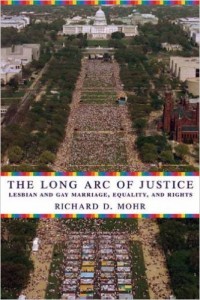

The Long Arc of Justice: Lesbian and Gay Marriage, Equality, and Rights

The Long Arc of Justice: Lesbian and Gay Marriage, Equality, and Rights

by Richard Mohr

Columbia University Press

160 pages, $22.95

AT AN EASILY DIGESTIBLE 136 pages, The Long Arc of Justice is a powerful little book of applied ethics in which Richard Mohr devotes his characteristic analytical rigor to a broad range of important gay and lesbian issues. For those familiar with Mohr’s work in GLBT philosophy, much of this book’s philosophical machinery will be familiar, as it draws from many of his prior publications, including his often reprinted article, “Gay Basics,” his work on recent Supreme Court rulings, and especially his 1994 book, A More Perfect Union: Why Straight America Must Stand Up for Gay Rights.

To begin where the book ends: in the final paragraph, Mohr quotes Will Rogers for having “correctly recognized the limited role of reason in politics when he quipped, ‘People’s minds are changed through observation, not through argument.’”

The Long Arc of Justice is intended as “a handshake of greeting from gay experience to the hearts and minds of mainstream America.” By drawing attention to what is particular to gay and lesbian experience and applying to that experience moral precepts and arguments that Americans as a people have worked through in other areas of national life, Mohr aims to elevate the quality of the debate about policy issues affecting America’s lesbian and gay citizens. While the book is about much more than gay marriage, this issue seems to be its emotional heart, and Mohr has never written more eloquently or with such feeling. For example, he closes Chapter Three with a brief but powerful vignette of a gay male couple, long married in their own eyes, one on his deathbed, each professing his love. As Mohr emphasizes throughout the book, it is this sort of story that packs a punch to the moral gut and is most effective in changing hearts and minds in the general public.

There is much to like in this little book and little to complain about—but I’ll give it a shot. First, I was never convinced by Mohr’s discussion of natural law in “Gay Basics,” and my concerns re-appear with the new volume. Mohr writes: “Finally, people sometimes attempt to establish the authority for a moral obligation to use body parts in a certain fashion simply by claiming that moral laws are natural laws and vice versa.” A few lines later he again characterizes the anti-gay view as holding “that natural laws in the usual sense (E = MC2, for instance) have some moral content.” But this does not accurately represent Natural Law theory as it derives from Aquinas. This tradition has never equated the laws governing the natural order with those governing human beings. Moral laws are “natural” inasmuch as they derive from our human nature, which is not to be confused with the order of nature that Einstein was describing.

Second is a quibble that’s nevertheless central to one of Mohr’s arguments. In discussing the current U.S. policy on gay service in the military, he states that “Lesbians and gay men are barred from military service.” This is not actually the case, as Mohr is clearly aware. The 1993 compromise dubbed “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” explicitly ended the outright prohibition on gay service, allowing gays to serve under strict—and clearly unjust—restrictions on their speech and behavior. Mohr continues to speak of the new policy as a “ban” on service when in fact it is a ban on speech—a different injustice altogether.

Finally, he incorrectly characterizes the Supreme Court’s ruling in the Boy Scouts case (Dale v. Boy Scouts of America) as falling under freedom of speech and political rights rather than primarily freedom of association. This leads him to worry unnecessarily about a dangerous precedent whereby all civil rights laws could be declared unconstitutional: “The case held that the Boy Scouts’ firing of a gay employee had an expressive content. It made a political point, and so was protected by freedom of speech.” But the principal basis for ruling in favor of the Scouts was that, as a private association of individuals, they had the right to discriminate against homosexuals by defining the membership of their association and its views and values as they saw fit. It was not merely that the firing was deemed protected as speech making a political point.

Mohr sees gay and lesbian rights as the test case of whether America is fundamentally committed to the general values of liberty and equality, or whether it is committed to some specific vision of what constitutes proper living. It is frightening to see the choice presented in such stark terms. And while Mohr is occasionally prone to dramatic overstatement, I think he’s pegged the critical issue that faces us as a nation. Despite the recent backlash, Mohr comes down on the side of optimism and expresses a cautious hope that America may yet make the right choice.

James S. Stramel teaches philosophy at Santa Monica College.