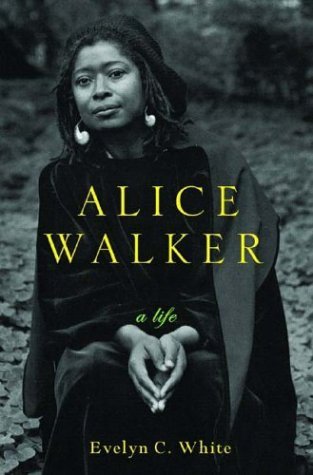

Alice Walker: A Life

Alice Walker: A Life

by Evelyn C. White

Norton. 496 pages. 29.95

THE LIFE of Alice Walker, born in the segregated South to sharecropper parents, is a lens through which a painful part of this country’s history can be closely observed. Walker’s life story has in many ways been a matter of public record. Her autobiographical essays have been widely published, and the video of her life (Alice Walker) is eye-opening for its depiction of the Jim Crow world of her childhood, where there were “whites-only” and “colored” drinking fountains, restrooms, and building entrances and exits.

While she reached the peak of her fame over twenty years ago with the publication of The Color Purple, and while many readers may not be able to recite the name of her latest novel (it’s Now Is the Time to Open Your Heart), Alice Walker is still hard at work, and still a force to be reckoned with. Journalist Evelyn C. White has produced the first major biography of the writer, and has successfully assembled the pieces of Walker’s life and related them to her literary output. Walker cooperated fully with White for this book, providing numerous interviews and unrestricted access to her papers and files, while not requesting manuscript approval (for which White lauds her subject as “an undiluted champion of artistic freedom”).

The story begins in 1944 when Alice Walker was born in Eatonton, Georgia. An important force in her young life was her formidable mother, who insisted that her children—Alice was the youngest of eight—receive an education and not be sent out to work in the cotton fields as was expected. When Alice was eight she was blinded in one eye by a stray pellet from her brother’s BB gun and, because of her race, was not able to receive proper medical treatment. In many ways, this loss honed her powers of observation and opened her remaining eye to the injustices that surrounded her.

Despite the considerable obstacles, the young Alice proved herself a brilliant writer and received scholarships to study at Spelman College and later at Sarah Lawrence. And she found mentors all along the way. The radical historian Howard Zinn was her professor at Spelman, and Muriel Rukeyser, an important poet who was under-appreciated in her own lifetime, at Sarah Lawrence. After graduation, Walker received a grant to go abroad but decided instead to return to the South to work for the civil rights movement. She lived in Mississippi with her husband, Jewish civil rights lawyer Melvyn Rosenman Leventhal. Her second novel Meridian, published in 1967, was based on this period of her life, during which she gave birth to Rebecca Walker, her “movement baby.” It was also a time in which her interracial marriage drew fire from all sides, including the black community and the civil rights community, as well as white Southern racists. After the latter came close to murdering Walker and Leventhal one night, the couple felt compelled to acquire a gun and to keep guard dogs.

Walker’s best-known work is of course The Color Purple, published in 1979 and turned into a movie in 1984. The lesbian relationship between the two main characters, Shug and Celie, may have been reduced to a single kiss onscreen, but its impact was both deep and widespread. Her most heroic contribution to literature, in my view, is her series of essays dedicated to “rediscovering” writer Zora Neale Hurston, on whose unmarked grave she placed a headstone. In the foreword to Zora Neale Hurston: A Literary Biography (by Robert Hemenway, 1977), Walker writes: “We are a people. A people do not throw their geniuses away. And if they are thrown away, it is our duty as artists and as Witnesses for the future to collect them again for the sake of our children, and, if necessary, bone by bone.”

This compelling biography brings us the sources and inspirations for Walker’s formidable work while detailing the ups and downs of a vulnerable human being. Those looking for the dirt will find it here—her feuds with mentors Muriel Rukeyser and Tillie Olsen, the difficulties of her first marriage, her subsequent long-term partnership with the writer Robert Allen. The book gives a briefer account of her relationship with well-known singer Tracy Chapman, as well as with her other female lovers and a subsequent male partner. Just how these relationships influenced Walker’s work is not something that White elaborates, perhaps deciding that it’s best to let her most explicitly lesbian poetry speak for itself.

Janet Mason, whose literary commentary is aired on This Way Out radio, teaches at Temple University. Her poetry appeared in a recent issue of the Harrington Lesbian Fiction Quarterly.