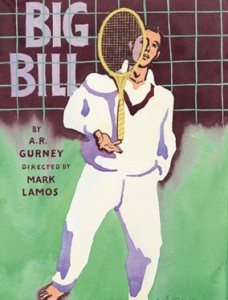

Big Bill

Big Bill

A play by A.R. Gurney

Directed by Mark Lamos

Lincoln Center Theater, New York

(until May 16, 2004)

The first line of dialogue in Big Bill is “Fifteen-love.” In A.R. Gurney’s bio-drama of the pre-World War II tennis phenomenon, Bill Tilden, it is no accident that the tennis term for zero is the adult emotion that, in Tilden’s life, is essentially absent. If you know your 20th-century culture heroes, you know that Tilden practically invented the modern game of tennis, transforming it from the polite recreation of country club devotees to a sport worthy of hard-won skills and a theatrical style of play. You’re also likely to know that Tilden’s late career sank from a successfully prosecuted court case in which he acknowledged an attempted seduction of a male minor.

Gurney is the dramatist of late 20th-century WASP America, and in such plays as The Dining Room, The Cocktail Hour, and Love Letters, he has anatomized the gentle decline of that imposing group whose mores once determined America’s social norms. In William Tatem Tilden II, born in 1893 of a prominent Philadelphia family, Gurney finds an enigmatic cultural icon: a handsome gentleman athlete of homoerotic impulse who had erotic fixations on the young ball boys staffing the competitive arenas. He developed successive crushes on these guileless teenagers. Yet Tilden imagined he could play a game of hide-and-seek with his sexuality with nary a price to pay.

If his sexual obsessions were somehow adolescent, the treatment Tilden received in the precincts of official tennis was not much better. An amateur competitor, he was expected to uphold the honor of the game for the sake of the U.S. Lawn Tennis Association (uslta). He could not play for professional stakes but instead plied the transatlantic circuit, aided by the charity of organizers and the favors of celebrity fans like Charlie Chaplin. Amateurs were expected to lodge with local fans or relatives; in Tilden’s case, family accounts and the occasional gig as a trainer kept him financially square. It was an article of faith that he remain a gentleman at all times, and he carried tennis court decorum, ever respectful of WASP social rules, right into his tortured personal life.

Gurney’s play weaves in and out of the early, successful career to the later decline when, as a paid professional, Tilden no longer commanded the court as he did throughout most of the 1920’s. Indeed, Tilden was ranked number one internationally from 1920 to ’25 and number one nationally for nearly the entire decade. He’s presented as a perennial man-boy, heedlessly cheerful in the face of financial stresses and obsessive ephebe fixations, incapable of making a clean break from his demanding father, likewise unable to force the uslta to accommodate to the financial realities of an amateur playing the international circuit. In Gurney’s hands, Tilden is maddeningly incapable of looking inside himself, arrogantly lording his excellence and his glamour over his opponents, smugly dismissing talented women players, and casually assuming that no one will notice that he’s keeping company with teenagers.

The portrait builds as a mosaic until finally every piece locks into place with climactic scenes of Tilden’s successive humiliations before the trial judge charging him with “lewd and lascivious behavior with a minor.” Here Gurney succeeds in establishing the claustrophobic conformity of the early 1950’s, when the barely understood science of sexology had yet to reach the halls of justice. John Michael Higgins, the actor who plays Big Bill in New York, who’s been so creepily happy and thoughtless through most of the play, now digs deep inside the man-boy to reveal a soul in torment. We see a Tilden incapable of lying outright to the court of law but still lying to himself about who he has been. A gentleman does not lie, but he also doesn’t say certain things aloud.

Big Bill may be faulted for being written from the outside—not of tennis or WASP society, but of the psychological closet. The play wants to stress Tilden’s Peter Pan-ness, but it cannot plant itself on the ground firmly enough to deal head-on with Tilden’s particular erotic obsessions. As for Higgins, in the least convincing stroke of his characterization, he offers us an athlete too boyish and effete to believably impersonate the sturdily tall and elegant Tilden—who, after all, dominated the court for more than a decade and wrote brilliantly about the sport. This hardly suggests the lightly swish quality that Higgins gives his younger Tilden. These weaknesses are balanced by a strong dénouement, with excellent supporting performances by Margaret Welsh and Jeremiah Miller as a mother and son who offer Tilden his final home after his imprisonment.