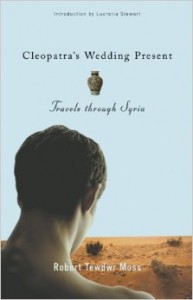

Cleopatra’s Wedding Present: Travels through Syria

Cleopatra’s Wedding Present: Travels through Syria

by Robert Tewdwr Moss

University of Wisconsin Press

245 pages, $24.95

ODDS ARE GOOD that no one at the Pentagon has read Cleopatra’s Wedding Present, even though it was first published in England in 1997. More’s the pity.

On the surface, Cleopatra’s Wedding Present seems right out of the “mad dogs and Englishmen” school of travel writing, a relative of Robert Byron’s Road to Oxiana. The anecdotal story line appears to be little more than a fey young man’s visit to some of Syria’s most famous—and obscure—tourist destinations. Moss sets himself up early in the book as he describes his traveling habits:

I selected a white linen shirt frayed at the seams, a dark blue cravat with tiny white dots, and a voluminous pair of navy blue linen trousers to which I attached a suitable fascist-looking belt, then doused myself with a few splashes of Malmaison by Floris and waited a few seconds for the rich, heady shock of carnation to assail my nostrils. Home at last. Perfume is the one luxury I allow myself when traveling into the unknown. It is evocative of comfort and dinner at eight, of the past but only the fragrant past, of the promising near future, of changing gear in the transition from one situation to another, a new start.

This opening impression is reinforced by the author’s early encounter with a stupendously alcoholic fellow English travel writer in the seedy bar of Aleppo’s Baron Hotel. There’s a good deal of cruising in bazaars and on train trips, and in fact Moss does take a lover, an ex-Palestinian terrorist named Jihad. Moss brings a queer historic-preservationist eye to the rapidly urbanizing city of Damascus. And there’s an incredible Fellini-esque visit to the Syrian International Film Festival, where Moss finds himself seated “next to a Malaysian man in a dog collar and a purple shirt who was the Vatican’s representative in Damascus.” Add to this that Moss can vividly describe the look and feel of a place as he journeys to spots well off the beaten track, and that his book has all the earmarks of an armchair traveler’s companion to places exotic and far away.

But for all these brilliant surfaces, something deeper is going on in this book. Perhaps it is the frankness of Moss’s account of his affair with Jihad that tips his hand. Moss acknowledges that he’s excited by danger, but walking alone through signless, slummy back streets to reach Jihad’s squalid room, he berates himself for his foolhardiness. He paints a fully human picture of his lover, one that’s unsparing about Jihad’s past life as a terrorist and his present life as a discarded cog in a remorseless political machine. This is not just a gay man scoring.

Two factors help account for the book’s success. First is the sheer amount of background information that Moss integrates into his narrative. Sometimes the information is given new urgency by its context, as when Moss visits the town of Hama. He describes its former loveliness and the terrifying events that culminated in the late Syrian dictator Hafez Assad’s order that the town’s inhabitants be massacred and the town flattened. He then takes us to the city’s mosque, which is now being rebuilt. Life goes on, uneasily. The book’s last excursion is to the north, near the border with Turkey. Moss is looking for an ancient Roman bridge, but his companion is obsessed by the Turks’ genocidal campaign against the Armenians, who were forcibly marched across hostile terrain to the Syrian town of Shaddadeh, which became for many their final resting place.

Yet for all the wretched terror invoked as Moss and his companion search the tombs of Shaddadeh, the most striking encounter comes when Moss visits the medieval castle that was the headquarters of “the Assassins,” which Moss calls “the world’s first terrorist organization.” As he describes the terrorist suicide tactics developed in the 11th century by the Shi’ite Muslims in their struggles with their Sunni overlords, it becomes icily clear that those tactics were the template for the 9/11 hijackers and for the horrible scenes that we’re becoming accustomed to seeing in Iraq.

The second factor that gives the book its unexpected weight is Moss’s eye-level view of life in a Soviet-style police state. Checking into a small hotel at the beginning of his journey, Moss becomes aware of which hotel employee is a government spy. Visiting with friends, he learns the secrets of survival in an environment that can suddenly become murderous. In conversations with the people he meets, he begins laying bare the habits of mind that develop when one lives to serve the State rather than vice versa. Perhaps what gives this book its compelling tension is the way in which there’s always a surface and a secret lurking behind the surface of everyone he encounters.

One final irony: when Moss left Syria he was seriously ill. Back in London, he returned to health and went to work on his memoir—only to be murdered the day after completing it. The final draft of the manuscript was lost when his computer was stolen, so this text, like the land it describes, is the survivor of a violent episode.

Jim Marks is Executive Director of the Lambda Literary Foundation and the publisher of the Lambda Book Report.