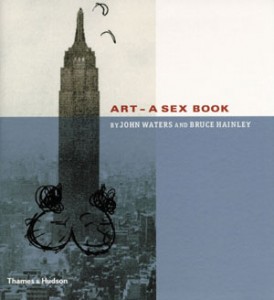

Art—A Sex Book

Art—A Sex Book

John Waters and Bruce Hainley

Thames & Hudson

208 pages, $29.95 (paper)

The comedies of John Waters are practical exercises in æsthetic philosophy. This theme is sometimes fairly explicit, as in Pecker, about a young photographer who “sees art when it isn’t there,” and in Cecil B. Demented, in which a terroristic movie crew kidnaps a Hollywood star and forces her to act in a film, doing her own stunts. In his 1974 feature Female Trouble, Waters cast his favorite leading lady, Divine, as Dawn Davenport, who fires a gun at the audience for art during her nightclub act. In all of his films, the so-called “Pope of trash” raises, or at least implies, questions about the nature of beauty. Thus it’s hardly surprising that Waters, in collaboration with independent curator Bruce Hainley, has produced Art—A Sex Book, which is at once an art exhibit showcasing an eccentric curatorial sensibility and an idiosyncratic, introductory survey of the contemporary art world (or some of it, anyway).

Fans of Waters’s movies and of his previous books, Shock Value (1995) and Crackpot (1989), will find much to interest them here. Those who are knowledgeable about contemporary art may be disappointed by the omission of their own favorite artist, or by the relative superficiality of the commentary. Much of what Waters and Hainley have to say is quite interesting, but they often don’t say enough. The bulk of the book contains photographs, a majority in color, including 175 works by seventy artists. Cindy Sherman, Robert Gober, Larry Clark, and Andy Warhol are some of the best-known artists represented, but most readers are likely to discover some new ones, as well. And there’s a fascinating (too brief!) appendix in which fourteen artists answer a set of pointed questions, such as “Can art be a bad influence on young people?” (Their consensus: yes, if it’s bad art.)

Not every work reproduced here deals explicitly with sexuality. There are things likely to speak only to the cognoscenti, such as Tom Burr’s models of sex-club architecture, and other works, such as Maureen Gallace’s painterly houses, that might not seem to belong in a book devoted to sex in art at all. “Perhaps there are images in the book which only the two of us find sexy,” Hainley notes. Some of the work, like Michelle Hines’s World Record #4, for which she videotaped herself having a prolonged bowel movement, is downright kooky. In a correspondingly whimsical (or, depending on your point of view, revolting) piece, Keith Boadwee is shown making a painting by excreting a tempera paint enema over a canvas. (When I showed Boadwee’s “Purple Squirt” to a friend, she laughed and asked, “But can he draw?”) As Waters explains, “Eccentricity is, to me, usually very sexy, because it’s … a kind of confidence.” At any rate, as Hainley remarks, “All art works reflect the viewer’s desire, not unlike a mirror.”

Reflecting his own desire, Waters’s private collection is represented by some of the works in these pages, including Mike Kelley’s 1987 painting Speech Impediment, which bears the inscription, “Thay you luv Thatan.” “The painting hangs in my bedroom,” Waters reveals, “right across from my bed. It’s the first thing I see every morning.” Waters also owns a work by George Stoll, mounted on the wall of his living room, in which a roll of chiffon toilet paper unspools gracefully to the floor.

Waters’s co-author is Bruce Hainley, a contributing editor at Artforum who teaches in the graduate program at Pasadena’s Art Center College of Design. Given his academic affiliation, he may perhaps be forgiven for occasional lapses into “academy-speak” in his portions of the text.

There’s bound to be something for everyone in these pages. I admired the witty photographs by Jeff Burton, including Untitled (Jacuzzi Waterfall) of 1992, in which one guy rims another. In a more recent work, the very sexy Untitled (Frill) of 2000, Burton has playfully positioned his model atop a large suitcase with its clasp obligingly open; he appears to be nude (what we can see of him, anyway; the picture is severely cropped) except for a red shirt with a delicate, rippling hem, bordered in black. It’s like an image in a skin mag, only smarter, more artful. One of the things this book investigates is the intersection between art and porn. I found it interesting to contrast Burton’s highly sophisticated work with the seemingly effortless photographs by Gary Lee Boas, which have the casual sexiness of snapshots. What gives them their charge is their intimacy and familiarity.

“You have to learn to see art,” Waters says, in what may be this book’s most interesting passage, “but that’s what’s so exciting. After going around to look at what’s in galleries all day, when you walk home—it doesn’t last for more than a couple of hours—but every single thing you see reminds you of art: the trash, the signs, the bus stop.” That’s a bit of æsthetic philosophy in a nutshell, but Waters adds that this state of grace isn’t permanent: “It fades a little as time goes by so you have to return to the galleries every couple of weeks to get the ‘art’ back into your life.”

Greg Varner is arts editor for The Washington Blade and has contributed to The Washington Post, Out magazine, Classical Music, and other publications.