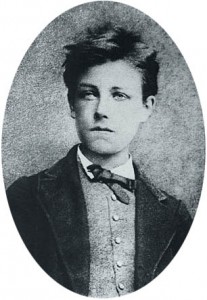

BACK IN 1953, noted scholar Wallace Fowlie observed of Arthur Rimbaud (1854–1891) that “Editions of his work multiply each year. More than 500 books about him have been written in all languages.” In the intervening years, books on the visionary teenage poet have continued to arrive. There was also a film version of Rimbaud’s affair with Verlaine, Total Eclipse, based on Christopher Hampton’s play and starring a pre-Titanic Leonardo DiCaprio. In a smartly concise new biography, Edmund White takes on the legendary French poet, traveling the familiar byways of earlier investigations but with a queer perspective. He also offers his own astute translations of Rimbaud’s iconic poems.

White’s compact biography manages to deal handily with his famously elusive subject by sticking closely to the documented facts while adding “some of my odd hunches about Rimbaud.” Unlike White’s previous bios of the indisputably queer Jean Genet and Marcel Proust, Rimbaud’s sexual proclivities present a more complex state of affairs. Observes White: “For those modern readers who like to think that sexual orientation is straight or gay and always neatly categorized, Rimbaud is worrisomely hard to classify.” All the available evidence indicates that Rimbaud was as experimental in sex as he was in his art. His famous statement, “Je est un autre” (“I is another”), attests to his disgust with received bourgeois values. Raised as a Catholic, he longed to revert to paganism and “re-invent love.” On the cusp of puberty, he wrote in “At the Cabaret-Vert” about a servant girl “with large tits and lively eyes … not one to be afraid of a kiss!” In a later prose poem called “Antique,” he’s intrigued by the androgynous “Graceful son of Pan! …Your fangs glisten. Your chest is like a lyre and tinklings move up and down your white arms. Your heart beats in that abdomen where slumbers your double sex.”

Inevitably, a major focal point of any biography of Rimbaud is his scandalous relationship with Paul Verlaine, the married and respected member of the Parnassian poets. After the sixteen-year-old Rimbaud arrived in Paris at Verlaine’s invitation, the two entered into an artistic and sexual relationship based on the younger poet’s radical theory of the reinvention of language through the systematic “disordering of all the senses.” A decade older than Rimbaud, Verlaine was immediately smitten with the handsome and precocious—if boorish and lice-ridden—escapee from provincial Charleville, a situation that the younger poet milked with impunity.

One of White’s main projects is to explode a key thesis of Enid Starkie’s 1968 biography, Arthur Rimbaud, namely that the androgynous Rimbaud was gang-raped by drunken soldiers from the Paris Commune of 1871, a conclusion she based partly on his poem, “The Stolen Heart.” Starkie argued that this was the “turning point in his development [and]… the source of much of his later maladjustment and distress.” White dismisses this claim as Freudian claptrap and points out the implausibility of soldiers in a city full of prostitutes and willing sex partners bothering to rape a fellow Communard, much less do so in front of one another.

In time, the intentionally boorish and arrogant Rimbaud was ostracized by the reigning artistic community, the Parnassians, and prevailed upon Verlaine, who felt that Rimbaud held the key to the ineffable, to leave the sterile security of his bourgeois married home life and join him on the open road as two absinthe-guzzling fellow vagabonds. Verlaine was the classic mean drunk, who could write elegant, impressionistic verse when sober but turn homicidal under the influence. As things turned out, the two poets—Rimbaud, the Dionysian pagan-provocateur, and Verlaine, the passive-aggressive, guilt-ridden lapsed Catholic—became as notorious as did Joe Orton and Kenneth Halliwell in a later day.

The climax to their toxic relationship occurred in Brussels when Verlaine, in a jealous rage, shot and wounded his lover. Arrested for attempted murder, investigators uncovered a piece of “incriminating” doggerel by Verlaine addressed to Rimbaud:

What hard angel stuffs me full

Between the shoulders, while

I fly off to Paradise…

O you, the Jealous one, who waves to me,

Here I am, here is all of me!

Still unworthy I crawl toward you—-

Mount my loins and trample me!

Next, Verlaine was subjected to a dehumanizing medical examination, and the doctors reported on his “small penis and its particularly small, tapering head.” After a bogus rectal exam, they concluded that “P. Verlaine bears on his person traces of habitual pederasty, both active and passive.” He was convicted of sodomy and served a two-year prison sentence. Despite the “disgusting prurience” of the day’s pseudoscience, White notes that “as a result of it, curiously enough, we know more about the intimate condition of (Verlaine’s) penis and anus than we do about the intimate anatomy of any other major poet of the past.”

Edmund White recently shared his thoughts, speculations, and convictions about Rimbaud with me from his home in New York City’s Chelsea district.

Michael Ehrhardt: Rimbaud believed he could become a seer through the re-invention of language, what he called the “alchemy of the word” and the “re-ordering of the senses.” In his famous poem “Voyelles,” he claimed he could detect colors in words; he claims to have invented the colors of vowels. The condition of “synesthesia” is reportedly common among artists and poets. Do you think he suffered from it?

Edmund White: A person who is capable of synesthesia might see colors in the sounds of vowels or in listening to music. While that’s a fascinating part of his work, I think he was influenced in this respect by Baudelaire, who was the great apostle of the idea of synesthesia. Baudelaire’s other famous dictum was to “be drunk, always.” Rimbaud and Verlaine were always imbibing absinthe, which was believed to produce a state of hyper-creativity. They smoked hashish as well.

ME: Do you believe Rimbaud was really convinced he could transform life through poetry?

EW: He did believe in the disordering of the senses, of creating a kind of liberating chaos. It might come at a terrible cost to you, not to mention to your friends, but that’s all right, because out of this great disorder comes this great poetry. After all, whereas prose is realistic and chatty, poetry has an exalted side to it, where you transform the everyday into the fantastic. For instance, Rimbaud writes about seeing a mosque instead of a factory. He took the idea of being a mage, or seer, quite seriously. He even read books on alchemy and magic. There’s a famous letter that he wrote called the “Lettre du Voyant,” which he wrote to two different people and stated that the poet must be a kind of seer. Rimbaud’s literary era was really at the height of the Romantic period with a capital R, and the notion of the artist was to achieve the sublime. He seriously believed that poetry had these remarkable powers. And when it failed him, or didn’t work out that way, he abandoned the whole project with a lot of anger and declared it hogwash. His career as a poet was a very brief, flaming career.

ME: It’s fascinating to think that in America Walt Whitman was singing “the body electric” and celebrating the “beautiful and sane affection of man for man,” and died a year after Rimbaud did in 1892. Rimbaud was a voracious reader; do you know if he ever read Emerson or Whitman?

EW: There’s no evidence of that. But probably not, since, while Rimbaud was very proficient in languages, his grasp of English wasn’t all that good. And Whitman hadn’t been widely translated during his lifetime, so he couldn’t have been an influence. Also, in a provincial village like Charleville, books were scarce and too expensive for a student. When I was doing my research on Genet, who was brought up in a similar village, I discovered that there were only about forty books available there. Remember, this was the era before public libraries. Rimbaud knew the ancient Greek poets and was proficient in Latin. He borrowed all the latest poetry books and journals from his professor Georges Izambard.

ME: Balzac, who was a follower of the mystic Swedenborg, and had already published his “Seraphita” in Rimbaud’s era, wrote about an androgynous, angelic creature of a higher intelligence, which seems to anticipate poems like “Génie” or “Antique.” Could that have been one source for his poems?

EW: Possibly. In Charleville, he borrowed books from an obese, older gay man, Charles Bretagne, whom he’d met at a local café and befriended, and whose opinion he respected. These were books about alchemy, mysticism, and the occult, which were very popular at the time. Swedenborg’s philosophy was widespread and had already influenced writers such as Blake and Baudelaire. Baudelaire’s famous poem “Correspondences” and longer prose poems must have had an influence on Rimbaud. These studies had a big influence on his poetic language. He also consumed books on science and the latest technology, which encouraged him in his visions of a utopian future. In London, he was constantly going to the library to keep up with the latest developments.

ME: Verlaine had never met Rimbaud before he came to Paris, right?

EW: Right. Verlaine didn’t even know Rimbaud was young and cute; it’s one thing to invite someone if you know they’re a hot sixteen-year-old on the make as a writer—but he was actually impressed by the poetry. Rimbaud arrived with a secret weapon in his baggage—which was “Le Bateau Ivre,” “The Drunken Boat” —and he read it to a group of poets, and they were just bowled over because no one had ever written anything like it. Mind you, they were competitive artists, not ready to concede their preeminence to a sixteen-year-old raw peasant. But they could all see what a genius he was. Remember, Verlaine’s own poetry took off after he met Rimbaud. I love Verlaine’s poetry as much as I do Rimbaud’s, and I think he was a great genius. But it is true that he responded to the challenge that the younger poet represented. Yet Rimbaud’s behavior was so reprehensible at times that he couldn’t help put the others off. For instance, people would give him their maid’s room to live in, and then he’d piss on everything. Or he’d stand in the window nude and jerk off, or break their heirlooms. He wasn’t a very nice guest.

ME: Did you find any evidence of Rimbaud’s homosexuality before he met Verlaine?

EW: Well, he did write a lot of poems in which he daydreamed about girls. But in the 19th century, of course, society didn’t group elements together the way we do today. Verlaine, like Oscar Wilde, was married and a father, and even wrote a lovely poem about how much he loved and physically desired his wife. That he, like Wilde, was attracted to a beautiful boy, was embraced as part of the Greek ideal in which the older man loves the young ephebe and guides and nurtures his intellect. For instance, all of Wilde’s affairs—apart from Lord Alfred Douglas—were with younger, pretty men.

ME: So, Verlaine and Rimbaud were both bisexual?

EW: Yes, and with Rimbaud his sexuality seems to be part of his philosophy of experimenting with all kinds of experiences and sensations. In his “Lettre du Voyant,” he states that the first objective of a seer is to know every part of himself. And you can only know this through the senses. And, after all, he did have respect for Verlaine as a poet.

ME: There’s an almost Oedipal quality to Rimbaud’s love-hate relationship with the older Verlaine. He admires Verlaine the poet, but having grown up constantly abandoned by his scapegrace father, Rimbaud must have subconsciously resented Verlaine for abandoning his infant son Georges. After the whole squalid scandal, couldn’t Rimbaud’s total renunciation of poetry be seen as a metaphor for the seer putting out his eyes to wander in the wilderness?

EW: I don’t believe in the Freudian theory of an Oedipus complex; I think it’s a lot of pseudoscience.

ME: How do you account for Rimbaud’s cruelty towards Verlaine, such as the incident of stabbing him in the hand?

EW: I think there must have been some elements of sadistic provocation in Rimbaud, and I imagine Verlaine enjoyed to some extent playing the part of the put-upon victim. But I don’t think there was anything subconscious or Freudian about it.

ME: Do you believe that Rimbaud’s renunciation of poetry at the tender age of 21 is part and parcel of his legend?

EW: Yes. In the aftermath of all these romantic notions of the artist, he turned his back on literature, and money took the place of art. He wanted money— to be rich, but he wasn’t a very good businessman. It’s like what Jean Genet said about himself: the only thing he could do was be a genius, and when he wasn’t being that, he was just a bad thief. It’s like people who have no talent—they only have genius. In Rimbaud’s case, I think he really reverted to his mother’s values. She was something of a hard-bitten peasant woman who believed in distrusting everyone and was paranoid about everything and tried to accumulate a small fortune and bury it under the bed. Later, Rimbaud kind of subscribed to that notion. He wrote an enormous number of letters to his mother and sister from Africa, always complaining about his luck and about how awful it was to live there. But he was convinced it was worth it, and he would eventually amass a fortune.

ME: After his rupture with Verlaine, Rimbaud lived in London with Germaine Noveau. Were they lovers as well as colleagues?

EW: Germaine Noveau, who was a would-be writer, was small, dark, and good-looking—according to photos of him. He and Rimbaud were probably lovers for a short time. But Nouveau became an eccentric and ended up begging outside of churches.

ME: Did you ever find any hard evidence that Rimbaud and his servant boy Djami were lovers?

EW: No, but he did leave Djami something in his will, and he was calling for him in his delirium just before he died. Rimbaud also had a native mistress in Abyssinia; she was black with European features.

ME: Can you imagine poets such as John Ashbery and James Merrill (with his visionary “Scripts for the Pageant”) enjoying the same future, undiminished fame as Rimbaud?

EW: I think Ashbery’s poems aren’t as translatable or as universal. They’re very discursive and free-associated. While Merrill’s, although brilliant, are often unfairly interpreted as effete, or—

ME: Too baroque, too gay?

EW: Yes. His work is already beginning to fade from the shelves. It’s not yet taken as seriously. I think the writer who comes closest to Rimbaud is the British poet Jeremy Reed, whose influences include Rimbaud, Artaud, and Genet.