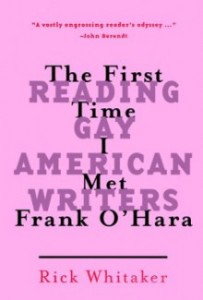

The First Time I Met Frank O’Hara:

The First Time I Met Frank O’Hara:

Reading Gay American Writers

by Rick Whitaker

Four Walls Eight Windows. 231 pages, $20.

Rick Whitaker introduces the essays in his new book, The First Time I Met Frank O’Hara: Reading Gay American Writers, by suggesting that a writer’s sexuality may influence not only what he writes, but also how he writes. While this is nothing new in the realm of literary inquiries, it’s a worthy question and will snag the attention of many readers.

Our sexuality undoubtedly does influence how we create our poems and stories, but Whitaker provides few lasting or groundbreaking observations on this score. What he has succeeded in doing, while a less ambitious project, is to set forth one gay man’s smart, easily digestible reactions to the gay American writers he’s come to love. In this sense, it is a fairly engaging “reading journal,” though it rarely rises to the level of “literary criticism.”

Whitaker discusses with enthusiasm and some degree of fluency the literary style of his subjects, which include both the well-known and lesser-known writers of the last 200 years: Whitman, Dickinson, Melville, Frank O’Hara, James Baldwin, Gore Vidal, and Andrew Holleran, and minor writers like Fitz-Greene Halleck, Jane Bowles, and David Wojnarowicz. (In the cases of Dickinson and Whitman, Whitaker focuses on the poets’ letters, and wisely so; he’d be hard pressed to add anything new to the tomes already written about their verse.)

A chapter on Gertrude Stein is perhaps the one that comes closest to making a salient point on how sexuality influences one’s writing. Whitaker argues that Stein would never have developed her wildly individual and challenging voice if she’d been able to write more openly about her sexuality. Drawing liberally from writings like the famous “Miss Furr and Miss Skeen,” he points out Stein’s gift for irony, wit, and playful experimentation with language: “[H]er inventiveness as a writer set her free to find expression for what she found within herself.”

Whitaker attempts a similar mode of analysis when looking at Hart Crane’s writing, this time arguing that the “turbulence” in his work was the result of his sexual orientation. Here one might complain that Whitaker focuses too much on the biography side of the equation (focusing on Crane’s suicide) and not enough on the poetry side.

His chapter on Whitman’s Civil War experiences—through his letters—with the wounded and dying soldiers is enjoyable and provides some worthwhile material. It’s telling to see the young men through Uncle Walt’s eyes, and to read his tender, sympathetic prose. Unfortunately, Whitaker draws facile and simply wrongheaded comparisons between past and present experience. For example, he argues that Whitman’s life was “a kind of precursor to similar experiences many gay men had in the 1980’s and 90’s when our friends and lovers were dying of AIDS.” Later, he compares a young soldier of the 1860’s to a “proud, rebellious gay young man circa 1988.” These linkages seem to have no apparent purpose other than to showcase the author’s cleverness for coming up with them.

Whitaker agues that Emily Dickinson’s love letters (to her friend and sister-in-law, Susan Huntington Gilbert) can be compared to 12th-century French troubadour poetry and its vaunting of a “refining and purifying love.” This is an interesting proposition, but what’s far more fun for the reader (and far more useful in the space of an essay) is simply reveling in the overtly romantic and intensely dramatic prose that Dickinson dedicated to the woman she seemed to be romancing.

At the end of the book, the author spends a scant twenty pages on what he terms “The New Century,” somehow exemplified by poet Henri Cole (admittedly one of the greats writing today) and travel writer Tobias Schneebaum. This final chapter seems so obviously tacked on that one wonders why it was included at all.

Whitaker’s talk of a “gay sensibility” is too general to add much to the larger debate about this issue. A “gay sensibility,” he says, is “above all, original and fresh”—two of the more overused and fuzzy words that one could have chosen. He adds that the gay writing is “clever, scornful of laws, introspective, energetic and sexy.” Why not just describe the writing as “daringly pink”? How is Whitaker not simply describing good writing, or avant-garde writing, or postmodern writing? Doubtless gay writers’ sexuality “has made an important impact upon the ways they devised to compose poetry and prose.” But what precisely is the nature of this impact? While Whitaker offers up the raw material with which to explore this question, he falls short as guide to any real answers.