This article was translated from the German by Maxim Bohlmann, the son of Bruno Vogel’s friend Otto Böhlmann. The younger Bohlmann was born in South Africa and currently lives in California.

WITH HIS ANTI-WAR NOVEL ALF, from the year 1929, the Leipzig writer Bruno Vogel (1898–1987) acquired a prominent place in gay literary history. “Vogel’s Alf is tremendously lifelike, a deep and richly thoughtful book. It should be read by all people, especially all young people,” wrote Walter Schönstedt (1909–1961) enthusiastically at the beginning of 1930 in Reports of the

Scientific-Humanitarian Committee. In 1977 the book appeared in a third edition in Germany, and in 1992 the British Gay Men’s Press published an English translation of Alf (by Samuel B. Johnson) in its series Gay Modern Classics.

The novel, which Vogel himself subtitled “A sketch,” describes the love between two high school students, which ends in tragedy. It is the time of the First World War. When Felix acknowledges that the feelings he and Alf experience for each other go against the morals of their environment, and that gay sex is punishable as indecent assault, he pulls back, deeply disconcerted, from his friend. In his pain Alf volunteers for military service, and shortly before a visit home on leave can bring reconciliation, he dies a “heroic death” at the front. The letters he wrote during his time as a soldier are the only things remaining of him. Full of guilt and regret, Felix swears to his dead friend that from now on he will “join in the fight against evil and stupidity,” that he will do his part “so that no one else is forced by ignorance to go through the hard times the two of us went through.”

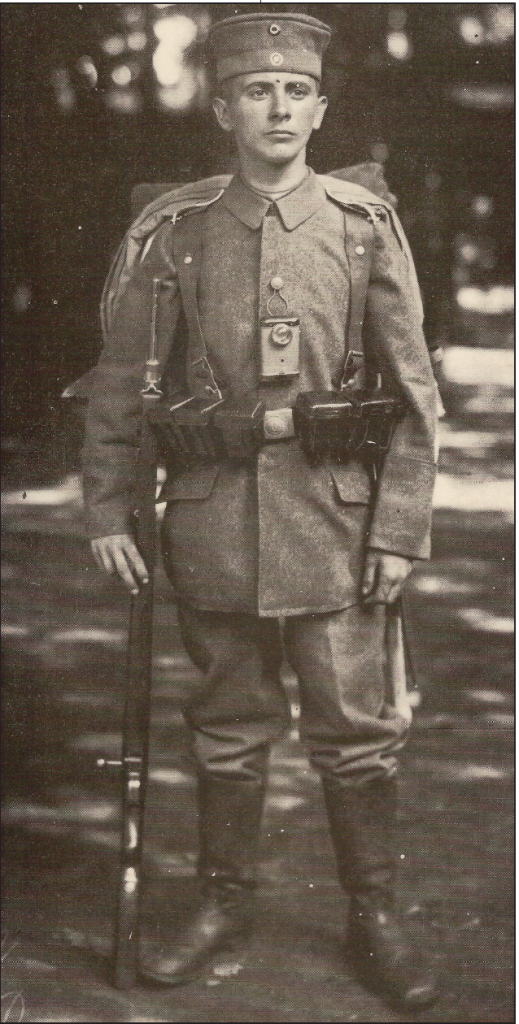

Bruno Vogel’s Alf is a book against the war, and it uncompromisingly settles accounts with the social order in Wilhelm’s Germany. It attacks, above all, the schools and the church. The novel is, however, also a work of resistance against the German “Homosexual Paragraph” §175, which was only abolished in 1994 during the German unification process. This change in penal law was preceded by an almost one-hundred-year struggle by the German homosexual civil rights movement, begun by Magnus Hirschfeld’s petition to the German Reichstag of 1897, up to the actions by the newer gay and lesbian movement, which had grown ever stronger after 1971. Bruno Vogel lived until 1987 in London, having moved there in 1953. In his later years, researchers who had only recently begun working on gay and lesbian histories sought him out for accounts of his experiences during the days of the Weimar Republic. Although his novel Alf bears unmistakably autobiographical traces, until recently little was known about Vogel’s life. In the English-speaking world, it was even held that Vogel was not gay at all but lived with a woman. That is clearly wrong, because even a fleeting look into Vogel’s autobiographical notes teaches one better—to say nothing of the knowledge obtained from recent research. Bruno Vogel was born in Leipzig on September 29, 1898, the son of animal keeper Emil Bruno Vogel and his wife Adelheid Josephine (born Jarolimek). However, he spent his early childhood years in Bohemia. He himself later assumed that this was why he never developed a close relationship with Germany as his “Fatherland.” After attending the Realgymnasium at Glauchau in Saxony as well as the Nikolai Humanistic Gymnasium in his birth city of Leipzig, he was conscripted into war service in 1916 at the age of eighteen. He fought first on the eastern border of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, then in the Baltic, and, at the end of 1917, in Flanders. His experiences during the Great War were expressed in numerous anti-war narratives. They appeared in book form in 1925 and 1928 under the titles Es lebe der Krieg! (“Long Live War!”) and Ein Gulasch und andere Skizzen (“A Goulash and other Sketches”). As in Alf, homosexuality plays a significant role in three of the seven stories in Ein Gulasch. Vogel’s first work soon found its way into the courts. Under the accusation of “sexual offense” and “blasphemy,” the author of Es lebe der Krieg! was sentenced to a heavy fine by a Leipzig jury; but in 1926, in the ensuing appeal, he was acquitted. Nevertheless, his book remained banned in the Weimar Republic and appeared only in “castrated” editions. Alf, in the second edition of 1931, could only appear in heavily a form. By then Vogel no longer lived in Germany, but in Austria. In 1922 he had been encouraged to found the Leipzig–based homosexual organization Gemeinschaft Wir (“We the Community”) by none other than sex researcher Magnus Hirschfeld (1868–1935). By statute the group was also to work in the Leipzig area as the Scientific-Humanitarian Committee (WhK). At the same time, Vogel came into conflict at his parents’ house because of his homosexuality. His parents found him in bed with a male friend and threw him out on the street. At Hirschfeld’s suggestion, Vogel moved to Berlin in the mid-20’s. Here he founded, together with the journalist Kurt Hiller and others, the Revolutionary Pacifists Group (GRP). As late as December of 1932, this group spoke out against the re-establishment of compulsory military service in Germany. Until 1928, Vogel was a member of the Social Democratic Party (SPD). However, he left the party when it agreed to the building of armored cruisers. In the same year he became chairman of Hirschfeld’s WhK. For a few months he held, in his own words, “a remarkably subordinate and uninteresting job” at the Berlin Institute for Sexual Science, and in November 1929 he was selected as the third assessor of the executive committee of the WhK. In 1930 he wrote numerous reviews for Reports of the Scientific-Humanitarian Committee. But later he would have little positive to say about his Berlin time: “brrrh, that was a bad period,” he wrote in a 1949 letter to Kurt Hiller. Vogel left Germany in the summer of 1931 for Vienna, where his friend Otto Böhlmann had begun to study medicine. The two men knew each other from Berlin. Vogel took a room and began to work for the publisher Karl Schusdek. Having worked in Berlin on Magnus Hirschfeld’s Moral History of the Post-war Period (1931), he now translated French detective stories like Fantômas and Murder in Monte Carlo. Apparently, Vogel and Böhlmann initially felt comfortable in Austria, but soon after the Berlin Reichstag fire of 1933 the two friends went to Switzerland. Vogel and Böhlmann traveled to Paris via Zurich and Valais, and then on to Norway, where they arrived in October 1933. In January of 1934, they established themselves in Tromsø, north of the Arctic Circle, where they rented a barely heatable summer hut. The living conditions for the two friends were extremely difficult. They suffered from a shortage of money and the absence of employment possibilities, and Vogel had serious and recurring health complaints. Böhlmann traveled on to England at the end of 1934, while Vogel remained in Norway, although he did not have a work permit there. The German consulate in Bergen held back his passport, which he’d submitted for an extension, because the Berlin Gestapo had imposed a passport suspension on him. His three published books were on List One of “harmful and unwanted literature,” which extended to “all further writings.” Thus they were banned in the German Reich. Vogel worked in Tromsø as a language teacher and occasionally earned a little money from articles for German-language and Norwegian newspapers. The translation of his texts was done by the young Norwegian Gudmund Sørem, with whom Vogel had become acquainted in 1934. Through the agency of the Norwegian minister of foreign affairs, Halvdan Koht, Vogel finally received new travel papers, and on January 27, 1937, he left Tromsø for London in order to travel from there to South Africa. Böhlmann had already gone to South Africa in 1936. Gudmund Sørem followed Vogel and Böhlmann from Norway in 1938. Today one can only speculate about the kind of relationship the three friends may have formed. While Vogel lived a life as a self-declared homosexual, both Böhlmann and Sørem later married and had families. Nevertheless, Vogel maintained his friendship with them across borders and continents until the end of his life. In the South African city of Benoni, he lived with the Böhlmann family from time to time—and was obviously troubled by the jealousy of Otto’s wife, Maria Susanna (née Pretorius). “Oh, were he less married,” Vogel complained about Böhlmann in a 1945 letter to Kurt Hiller. As for Sørem, who in the meantime had returned to Europe, Vogel remarked two years later: “Gudmund, the poor thing, he had to get married—he has a horrible period behind him.” Bruno Vogel maintained himself reasonably well in South Africa through typewriter work and language instruction, while Otto Böhlmann moved from place to place as a traveling salesman for brushes, vacuum cleaners, and brooms. This was also how Gudmund Sørem earned a living. But after Nazi Germany had invaded his homeland, Norway, Sørem volunteered in the South African Army, and at the beginning of 1942 Vogel followed his example. For the second time in his life, the declared pacifist Bruno Vogel performed military service, until he was discharged on medical grounds in 1944. After World War II, Vogel began as a reporter writing for Forward; he also reviewed books for other papers such as Common Sense and Jewish Affairs. But he was troubled by stomach and intestinal problems and was stricken with nervousness. As the living conditions in “sunny Sadistan,” as he called the apartheid state of South Africa, became ever more intolerable for him, he emigrated to England in early 1953 and settled in London. Here he renewed contact with Kurt Hiller and found employment at the Wiener Library. EVEN MANY YEARS after his return to Europe, Vogel still considered South Africa to be his home. He became involved in the anti-apartheid movement in England. In letters to Hiller he wrote that his heart was still with “the Magnesie,” which is what he called the gay and lesbian emancipation movement, alluding to Magnus Hirschfeld’s name. But his true interests lay in southern Africa. Already in 1946, for financial reasons, Vogel had rejected co-operation with the Swiss homosexual magazine Der Kreis: “I could not write anything that would not give me the least prospect of payment; I am economically in such a way.” Beginning in 1966, he tried in vain to find a publisher for his novel Mashango, written in English. In it, he treated the history of a friendship between a young black man and an older white man. Obviously the novel had no happy ending; several times in letters Vogel called it his “double murder history.” His collection of short stories Slegs vir Blankes (Afrikaans: “Only for Whites”) also remained unpublished. Both manuscripts have to be considered missing today. Bruno Vogel suffered his whole life from poor health, and complaints about his physical condition like the following ones in his letters to Kurt Hiller are legion: “I am stupid, dull, and blunt. Tired and irritated”; and “Here everything is adverse to me and most of it also disgusting.” Nevertheless, Vogel lived to a ripe old age, dying on 5 April 1987 in London’s Royal Free Hospital. He had spent the last years of his life in precarious financial circumstances and under the burden of old-age depression. Hardly anything is known today about his personal environment and his London friends. He might, however, have derived a certain satisfaction from the growing interest in him as a witness to social and political conditions while fascism unfolded. In 1966, the East German author and publisher Wolfgang U. Schütte made contact with Vogel. The exchange of letters between the two over many years led to a volume of stories by Vogel under the title Ein junger Rebell. Erzählungen und Skizzen aus der Weimarer Republik (“A Young Rebel. Stories and Sketches from the Weimar Republic”). It was brought out by the East German publishing house Tribüne. Vogel visited Schütte in October 1973, and also his birth city of Leipzig, for the first and last time since his emigration in the early 30’s. But the East German authorities made the visit of this British citizen to his old homeland fairly difficult. They housed him in the expensive foreign currency hotel Deutschland, in the city center, which drained all his money after only a few days. In the summer of 1977, the West Berlin historian Manfred Herzer visited Vogel in London, and in the same year Herzer arranged for a new edition of the homoerotic anti-war novel Alf. Vogel himself wrote an autobiographical epilogue to the new edition in which he again and again revealed his humor. Also, the sex researcher and author Charlotte Wolff (1897–1986) visited Vogel in the early 80’s to interview him about his relationships and experiences with Magnus Hirschfeld and other protagonists for the cause of homosexuals. So it was that, despite his literary failures of the post-war period, Vogel was not completely forgotten. But typically enough, Wolff recorded that Vogel always devalued his own abilities and achievements. In hindsight, he was not proudly fulfilled by a moving and upright life. “La vie continue,” Bruno Vogel wrote in August 1946 in a letter to Kurt Hiller, is what the “euphemism for our defeat” is called. Physically he had survived the period of National Socialist barbarity and of great misery in forced exile, but it seems that after the end of the war he never quite regained a successful foothold on life. His enduring works were all created before 1930. “Those were times of hope: Perhaps it was nevertheless possible—it had to be possible, through word and work to change the confused insanity of irrational aggression into delightful life-friendly reason,” he later wrote. In view of the double experience of war and exile, the hopes for the pacifist Bruno Vogel had proved to be dream and folly. Raimund Wolfert, who lives and works as a teacher in Berlin, is the author of a book on the Danish-German “International Homosexual World Organization” of 1952 to 1974.