WRITES EDMUND WHITE in his new memoir City Boy: My Life in New York in the 1960’s and ’70’s, “[Susan] Sontag once said to me … that in all human history in only one brief period were people free to have sex when and how they wanted—between 1960, with the introduction of the first birth control pills, and 1981, the advent of AIDS.” White’s move from Ohio to Manhattan in 1962 put him at the beginning of this unique period in the cultural history of the last century, allowing him to record his own experiences against a backdrop of a city just awakening to the possibilities of sexual freedom.

Near the midpoint of these two decades was the Stonewall rebellion in 1969, a watershed event in modern gay history with major, if often overlooked, significance for heterosexual liberation. City Boy contrasts the sexual Zeitgeist of New York before and after Stonewall, especially among White’s circle of friends (and tricks) as they expressed their nascent sexual identity in an increasingly adventuresome milieu, erotically speaking. After the summer of 1969, the hetero- and homosexual revolutions quickly progressed in tandem, but rarely overlapped.

In chronicling his growth as a writer within the rarefied world of gay literary lions and their revolving panoply of boyfriends, White provides all the dish one could hope for. But in addition to his reminiscences on famous friends and lovers, he also offers a before-and-after picture of his own shame and self-awareness, coupled with his concurrent progression from frustrated novelist to pioneer of gay fiction—a change lubricated with sex, art, drugs, and poetry—following the first eruption of gay liberation.

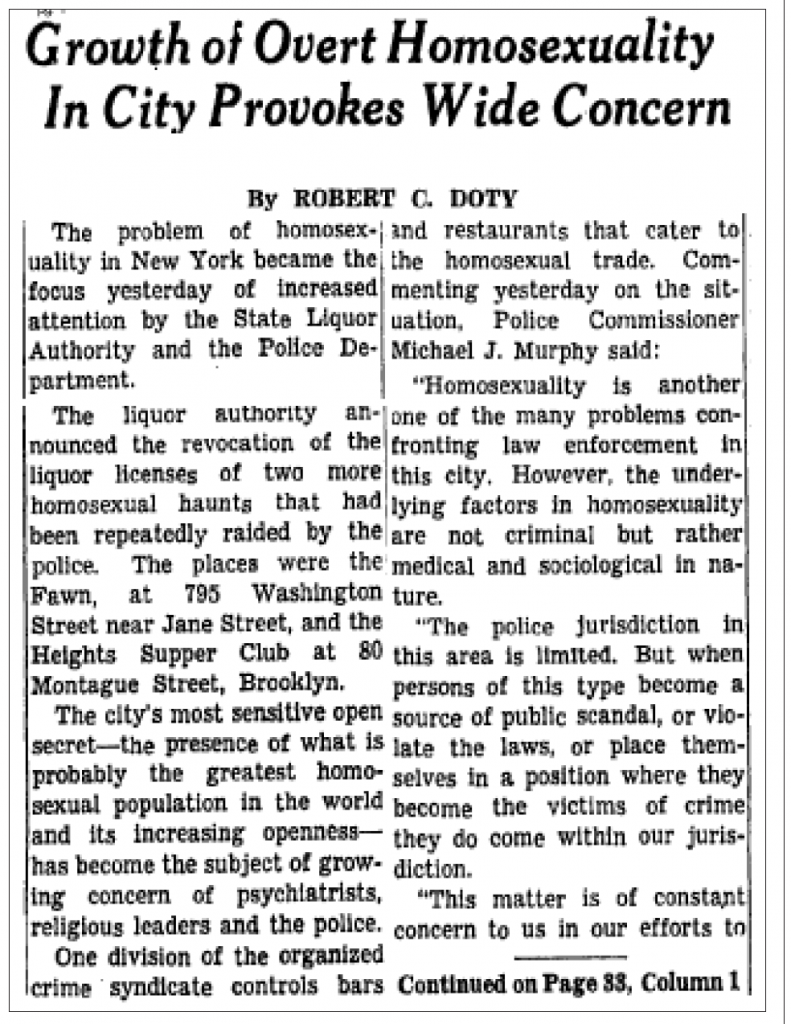

When White made the pilgrimage to New York in the early 60’s, as so many young gay artists had done before him, the powers-that-be were beginning to notice the rumblings of social upheaval. “The city’s most sensitive open secret [is]the presence of what is probably the greatest homosexual population in the world and its increasing openness,” warned a front-page exposé titled “Growth of Overt Homosexuality in City Provokes Wide Concern” in The New York Times on December 13, 1963, implying that the secret wouldn’t stay under wraps for long. Reporter Robert C. Doty, repeating the opinion of legal and medical experts, wrote, “the overt homosexual—and those that are identifiable probably represent no more than half the total—has become such an obtrusive part of the New York scene that the phenomenon needs public discussion.”

Helpfully, Doty proceeds to outline the gay scene that awaited Edmund White. Homosexuals “seem to throng Manhattan’s Greenwich Village, the East Side from the upper 40’s through the 70’s and the west 70’s. In a fairly restricted area around Eighth Avenue and 42nd Street there congregate those who are universally regarded as the dregs of the invert world—the male prostitutes—the painted, grossly effeminate ‘queens’ and those who prey on them,” he wrote with palpable disdain.

Shortly after his arrival, White noted that Mayor Robert Wagner had begun cleanup campaigns in anticipation of the 1964/65 World’s Fair in Queens, especially in these neighborhoods, to keep “undesirables” out of the view of tourists. Police conducted nightly sweeps through Washington Square Park (just steps from White‘s first apartment), locked down public toilets in the subways, and issued summonses to newsstands that sold physique magazines.

White ventured out to the bars despite police raids, a risk he was not alone in taking, as the indefatigable Doty hastened to observe: “Homosexuals are traditionally willing to spend all they have on a gay night,” he noted. “They will pay admission fees and outrageous prices for drinks in order to be left alone with their own kind to chatter and dance together without pretense or constraint.” What he failed to note is that gays were frequent targets of police entrapment at the bars as well as in cruising areas, while these establishments could have their licenses yanked at any time for serving drinks to “sex perverts.” Doty concludes that “a New York homosexual, if he chooses an occupation in which his clique is predominant, can shape for himself a life lived almost exclusively in an inverted world from which the rough, unsympathetic edges of straight society can be almost totally excluded.”

White tried hard to live in that bubble. Even though the city had already begun the economic slide that would bottom out in the 1970’s, the cheap rents and the chance to be surrounded by artistic ferment made up for the infrequent garbage collection, the muggings. and the police harassment. He got a tiny apartment with his first boyfriend on MacDougal Street in the heart of Greenwich Village, a roach trap befitting a struggling writer and an actor; he sipped espresso in the nearby Italian cafés with aspiring singers (one of whom was a not-yet-famous Cass Elliott of the Mamas and the Papas). He churned out a few plays and worked on a first novel.

But White’s middle-class upbringing still nagged at him. In a bid to satisfy his penchant for respectability, he took a job at Time-Life Books as an editor, and quickly fell into a boring routine. Valiantly he toiled at one mid-level editorial job after another, even doing a horrific stint at a chemical company, where he wrote press releases defending the firm’s toxic products. In every position he felt that his homosexuality, however carefully concealed, was a liability in any quest to find something better.

His disappointing days turned into nights filled with possibility. He emerged from his cocoon of propriety to cruise the streets, relishing the ever-shifting variables of the erotic dance. “Much of my spare time was devoted to sex—finding it and then doing it. … Typically we’d walk up and down Greenwich Avenue and Christopher Street—not with friends, which might be amusing but was entirely counterproductive. No, only the lone hawk got the tasty rabbit,” White remembers with glee.

White details not just the artful pantomime of cruising, with its specific signals, body language, and codes (“it was considered especially cheeky to ask for a light when you were already smoking”), but also the elaborate staging of the “trick pad,” the miraculous weekend transformation of a roach-trap apartment into a swinging bachelor’s hideaway. “I’d clean my apartment carefully, change the sheets and towels, put a hand towel under the pillow (the trick towel for mopping up the come) along with the tube of lubricant (usually water-soluble K-Y) … you’d place an ashtray, cigarettes and a lighter on the bedside table. You’d lower the lights and stack the record player with suitable mood music (Peggy Lee, not the Stones) before you headed out on the prowl. All this to prove you were ‘civilized,’ not just one more voracious two-bit whore.” Despite the concurrent police crackdown on cruising, White managed to avoid being picked up for disorderly conduct, a misdemeanor.

The dissonance between his straight-acting days and his hedonistic nights wore on White’s sense of himself. He half believed the psychiatric view that he was “sick” and a social misfit—and this was the progressive view of homosexuality at the time. New York psychiatrist Charles W. Socarides, the leading researcher into the “problem of homosexuality,” believed the condition was a neurotic adaptation resulting from a man’s too-close attachment to his mother in childhood (see Bates, Norman). White, like everyone he knew, had internalized the theory that homosexuality was preventable and curable. “In the late sixties I was a walking contradiction,” he writes. “I was still a self-hating gay man going to a straight psychotherapist with the intention of being cured and getting married. … If I could have stopped my ‘acting out,’ as my various psychiatrists called it, I would have.” Barring that, White turned his sights to his writing and wondered if he could make the connection between his artistic self and his sexual self.

White happened to be cruising in Greenwich Village on June 28, 1969, a dirty, muggy, tense night in the city. Police harassment had died down since the World’s Fair era, and men felt more comfortable hitting the gay bars around midnight, which is what made the raid on the Stonewall Inn so unusual and aggravating to the people there. No one was tipped off, as was customary, when agents from the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms began the raid. Patrons argued with cops from the Sixth Precinct and threw empty bottles while men in drag were loaded into the back of a police wagon. White found it all rather amusing: “I remember thinking it would be the first funny revolution. We were calling ourselves the Pink Panthers and doubling back behind the cops and coming out behind them on Gay Street and Christopher Street and kicking in a chorus line.” He joined the crowd in shouting “Gay is good!” and thought it was all a big party, a radical and joyful pushback to the false promises of psychiatrists, the media’s uncomprehending distrust, and the city’s ham-fisted policy of containment. “Up until that moment we had all thought that homosexuality was a medical term. Suddenly we all saw that we could be a minority group—with rights, a culture, an agenda. June 28, 1969 was a big date in gay history.”

It was also a significant moment in straight history, though for more obscure reasons. Stonewall made it possible to talk about homosexuality openly, in a nonjudgmental way; it became more acceptable for straight or bisexual people to try out same-sex desire now that homosexuality was gaining cultural approval. Stonewall cleared the way for people to learn about unconventional forms of heterosexual desire. The Joy of Sex, for example, by the British physician and novelist Alex Comfort, became an instant bestseller in 1972 by forthrightly answering the rarely-spoken questions of human sexual activity with wit and copious illustrations of a hirsute heterosexual couple enacting the various positions.

The Joy of Sex (1977) sold more than twelve million copies, prompting its packager, Mitchell Beasley, to approach White about authoring a similar book for gay men. The Joy of Gay Sex, written by White and Dr. Charles Silverstein, adopted the same pleasure-centric and positive attitude as its predecessor, with significant detours into topics one didn’t find in the original: coming out, queer baiting, trade, baths, and so on. White recognized the need for factual answers to the questions of gay existence that used to be found only through trial and error. In City Boy, White plays down The Joy of Gay Sex in his compendium of literary achievements, despite its commercial success. Curiously, he seems to view the book as a slightly embarrassing, did-it-for-the-money job, even though so much of his life at the dawn of the 70’s revolved around sex, and his research was conducted through first-hand experience. He did, after all, dedicate the book to “all my tricks.”

The Joy of Sex and The Joy of Gay Sex couldn‘t have come at a more appropriate moment. “For the first time I realized how much New York gay life had been changing all along,” even before Stonewall, White noticed. “Now it seemed as if ten times more gays than ever before were on the streets. With ten times as many gay bars. Here were go-go boys dancing under spotlights and hordes of attractive young men crowding into small backrooms.”

White made good use of the backrooms, even at the Manhole, a hardcore leather bar in Manhattan’s isolated meatpacking district north of the Village. But one sexual arena he seems to have avoided was the baths. There’s nary a mention of even the best known bathhouses in his fond descriptions of the decade’s sexual possibilities. Perhaps their popularity was a turn-off for White. The Continental Baths at the corner of Broadway and West 74th Street, for example, opened as a deluxe emporium for sex, but the nightly cabaret shows featuring nationally known entertainers attracted too many slumming straight couples for its gay clientele. The Continental Baths closed in 1975, a victim of its own fame. Ironically enough, the space reopened in 1977 as Plato’s Retreat, an enormous swingers’ club with a disco floor, buffet, and mattress rooms for heterosexual couples to get comfortable with other women or couples: no single men were ever allowed.

With the emergence of gay awareness after Stonewall, White carved out his niche in New York’s gay literary world, an elite club that required the right introductions and generous patrons. In 1970, a trick introduced him to the poet and critic Richard Howard, who became a close friend and was instrumental in getting White’s first novel, Forgetting Elena, published in 1973. Through Howard he met Howard Moss, the poetry editor of The New Yorker; critic and professor David Kalstone; and eminent poets James Merrill and John Ashbery. Gay men all, their cliquishness enhanced their elite status, as well as their magnanimity toward not-yet-published gay writers like White. Sex was the lingua franca of this rarefied world of poetry and art as much as it was on the street.

White was in awe of these new friends. Conscious of his place as the youngest and least famous writer at any given party, he observed how older poets nurtured the younger ones and leading intellectuals graciously brought the inexperienced philosophers into conversations. At country homes and beachside cottages, White and his idols gathered for nights filled with poetry readings, wine, and gay gossip. He tagged along when James Merrill dropped in on Galway Kinnell or Elizabeth Bishop; he accompanied David Kalstone to Rome and Venice, where they lunched with Peggy Guggenheim and the experimental novelist Harry Mathews. He attended piano recitals by Arthur Gold and Bobby Fizdale, with Jerome Robbins and assorted European royalty in tow.

Forgetting Elena finally brought White a taste of the literary achievement he had moved to New York to find. His profile grew and he began teaching creative writing classes at Yale, Johns Hopkins, and other universities, which opened more doors to famous friendships and acquaintances—with Lillian Hellman (whom he detested), William Burroughs (who creeped him out), Virgil Thomson, Michel Foucault, Christopher Isherwood and his young lover Don Bachardy, Robert Mapplethorpe, and Susan Sontag. No longer was he the neophyte among giants; White began to forge his own path and his own sensibility toward literature—specifically, gay literature.

In the introduction to The Joy of Gay Sex, White lamented the dearth of good gay writing. “The chief reason to mention [sexual]pleasures is that they are so seldom described, even by the men who know them best and relish them most. The imaginative literature produced by homosexuals still hovers in the gloomy shadow of Freud and other spoilsports, and all too many of the ‘serious’ gay novels read as though written half by Krafft-Ebing and half by Cotton Mather.”

A conversation with his friend, Rutgers University professor Richard Poirier, convinced him that he was on to something. White suggested that there was value in gay fiction; that there was such a thing as a gay sensibility in literature. Gays read and wrote literature differently from straight writers—an argument that enraged Poirier, who flatly disagreed that gay writers could be isolated from the mainstream, insisting that literature was universal and indivisible. “Before the category of ‘gay writing’ was invented, books with gay content (Vidal’s City and the Pillar, Baldwin’s Giovanni’s Room, Isherwood’s A Single Man) were widely reviewed and often became best sellers. After a label was applied to them they were dismissed as being of special interest only to gay people.” But White believed that gay literature was a valid genre regardless of who read it.

White’s decision to set himself apart in his fiction, to try to elevate the gay novel to newly respectable heights, had everything to do with his decision to live as an out gay man—unlike “all these writers I was meeting—Ashbery, Howard Moss, David Kalstone, Elizabeth Bishop, Richard Poirier—[who]might be open about their sexuality in their private lives, but no one in the general public knew about it.” White was inspired by his own experience living as a gay man in New York during the most sexually liberated time in history. With that realization, he broke with the old guard, his earlier mentors, and his own psychological closet.

Kat Long’s first book The Forbidden Apple: A Century of Sex & Sin in New York City was published in 2009.