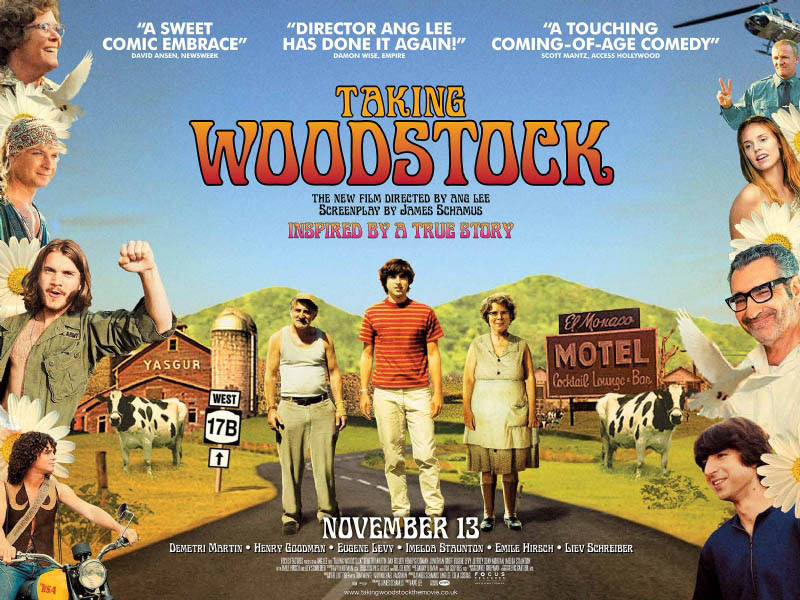

Taking Woodstock

Taking Woodstock

Directed by Ang Lee

Focus Features

Taking Woodstock, a critically acclaimed movie directed by Ang Lee, was a box office bust. Someone must have thought that a nostalgia flick about Woodstock would reel in boatloads of fifty-somethings. Once again, the Boomers have disappointed. Woodstock was many things to many people—a three-day celebration of rock music and hippie culture, a symbol of love and peace, a fifty-mile traffic jam on the New York Thruway—and its meaning continues to evolve. The festival even has a gay connection that Lee’s film brings to light. The Stonewall Riots had taken place only about six weeks earlier, and one of the rioters played an integral role in making the festival happen. Elliot Tiber (played by Demetri Martin) was a semi-closeted gay man with one foot in Manhattan as an interior decorator and the other in his parents’ run-down motel in the Catskills, where he toiled manfully to keep the place afloat. Tiber himself may have been a schlub, but by a weird coincidence he was still in touch with an old high school pal who was now a big-time promoter in need of a large outdoor venue. Tiber suggested Yasgur’s farm in Bethel, and the rest is history.

The movie, which is based on Tiber’s book, focuses on the back story of the festival and how it affected Elliot’s family and the people of Bethel whose lands were being invaded by 500,000 hippies. The movie doesn’t pull punches about Elliot’s homosexuality; nor does it dwell upon it. There are two scenes of physical intimacy involving a handsome carpenter: a long kiss at a private hoedown, and a quick bedroom scene, apparently post-coital, amid the busy preparations. One might have wished for a fuller exploration of Elliot’s gayness—the kiss appears to have been a coming-out moment vis-à-vis his hometown—but maybe that would have opened a digressive can of worms. Figuring prominently in the film is a drag queen named Vilma (played by Liev Schreiber), a Vietnam veteran who offers to provide security for Elliot’s family and friends. Vilma is a sympathetic character who’s treated with remarkable equanimity by the townsfolk. The message seems to be that amid so much Sturm and Drang—the first moon landing, the Vietnam War, the Woodstock Festival itself—being gay or dressing in drag just isn’t that big a deal.

Richard Schneider Jr.

Inferno Heights

Inferno Heights

by John Mitzel

Calamus Books. 249 pages, $15.95

This novel, which reads more like a series of satiric set pieces, takes place in hell. Its narrator is Bunny LaRue, a fabulously wealthy real estate titan who decides to open up new territory in the “swank circle of hell” where there’s no historical memory. There, people just make things up as they go along. Whether or not Bunny will be successful in his empire-building is this book’s conceit, but there’s no real suspense. Imagine a cross between a squalid Potemkin village and a planned retirement community in Florida. Ecological catastrophes have rotted all the flora and fauna, and the residents have fared even worse.

Firmly set in the 20th century, when pagers were the most annoying personal electronic device around, Inferno Heights is short on character development (none of the characters seems to have had a previous existence) and plot, but has a fair amount of snappy dialogue and many vivid descriptions of this imaginary world. Bunny finds backers, sycophants, and colorful personalities at every turn. Among other characters, there’s Big Louie, a straight man who wants to get exclusive rights to a chain of X-rated porn houses; Fluffy, a drag queen who could have featured in any early John Waters film and who stages S&M scenes in his home; and Bunny’s assistant, Helen Shumway, a lesbian who’s somewhat less repellent than the other characters. The narrator is given to ranting on topics such as the politics of the Reagan years, cooking shows, poetry slams (or, as he calls them, “poet laureate contests”), the sociology of victimization, grand opera, and pretentious magazines. It should be noted that the author owns Calamus, a well-stocked GLBT bookstore in Boston. He’s been a force in Boston’s gay publishing scene for many years and has written under several pseudonyms. One could grumble that the narrative doesn’t go anywhere, but then, where is there to go in hell?

Martha E. Stone