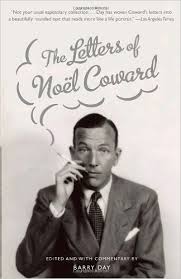

The Letters of Noël Coward

The Letters of Noël Coward

Edited by Barry Day

Knopf. 780 pages, $37.50

NOT MANY PEOPLE write real letters now, so those of us who like to read them—for their informal tone, their jokes, their opinions, their gossip—have to go to collections like this one. It’s an omnium-gatherum of hundreds of letters (and a sampling of light verse), written not only by the celebrated playwright, actor, stage producer, film director, songwriter, and singer of the title but also by some of his famous correspondents: G. B. Shaw, T. E. Lawrence, Virginia Woolf, Marlene Dietrich, Greta Garbo, Alfred Lunt and Lynne Fontanne, Somerset Maugham, Michael Redgrave, and Irene Worth. Add to these dozens of letters to and from theatrical or literary figures well known during Coward’s lifespan though now obscure, plus correspondence with his adored mother, his lover Jack Wilson, and other close friends. Add to that a circumstantial haze of news about fellow travelers whose letters are not included—Laurence Olivier, Vivien Leigh, Tallulah Bankhead, Beatrice Lillie (“Lady Peel” to her friends)—plus dozens of photographs, and you have a well-rounded portrait of one of the 20th century’s most discussed gay artists.

Barry Day, who has published seven earlier books on Coward, provides a connective tissue of narration between letters, giving the context and relevant facts about recipients. The result almost amounts to a biography, but Day doesn’t stick to chronological order throughout, sometimes outlining the whole history of a friendship by grouping correspondence with one person in a single section spanning a decade or more. With so much backtracking and cross-referencing, it’s a good idea to have the main lines of Coward’s life well in hand before you begin the book. Letters aren’t listed separately in an index, not all of them include a dateline, a greeting, or a complimentary closing, nor does the editor preface each letter with the kind of identification given in scholarly editions, such as “Letter from Coward to Alexander Woollcott” (plus the date). So it’s not easy just to browse around in the book; you have to read it from start to finish.

Doing that, you’re probably in for a few surprises. I expected to find the kind of burnished mondanité that Coward patented in plays like Private Lives or Blithe Spirit or songs like “Mad Dogs and Englishmen” or “I Went to a Marvellous Party”; and, sure enough, it’s there, along with camp phrases, thumbnail caricatures, and tart putdowns. (For example, he chaff-ingly addresses his friend Clifton Webb as “you wicked old drab.”) But the overall picture is of a man of unflappable optimism, good humor, and fair-mindedness. A large selection of letters is written to his mother Violet Veitch Coward, his opposite number in one of the 20th century’s great romances. (Coward’s endearment for her is “Darlingest,” in letters he signs “Snoop.”) Their mutual devotion is the best explanation for Coward’s sunny nature, one byproduct of which was an enormous enthusiasm for work, not just in writing and acting, but efforts of all kinds.

Before reading the letters, I hadn’t known just how patriotic Coward was, though the play Cavalcade and the film In Which We Serve in fact suggest as much. But during the Second World War he also served as a more-or-less secret agent of His Majesty’s government, giving up paid pursuits while he acted as something like a roving diplomat without portfolio and, more surprising, as an amateur spy. He tried, openly, to persuade the U.S. to join Britain in the war against Germany while relaying under-the-counter information to British Intelligence regarding the political opinions of influential people. If this sounds far-fetched, read the letter describing his invitation to stay a night at the White House with Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt, who spoke of their hopes to sway public opinion in favor of a military alliance between the two world powers.

Unluckily, the secret nature of his mission meant that he was tarred with the same brush that the press used on other British citizens who expatriated during England’s “finest hour,” such as W. H. Auden and Christopher Isherwood, to name only the most famous. All of these were maligned as yellow, and editorials insinuated that their sexual proclivities explained their cowardice: any red-blooded chap should join the armed forces or at least weather the London blitz along with loyal subjects who couldn’t or wouldn’t leave. Actually, Coward returned to London as  soon as he was allowed to and wrote that his experience there was one of the high points of his life. The terms of his service didn’t allow the secret agent to clear up the matter for many years after the war. A long-overdue knighthood came in 1970.

soon as he was allowed to and wrote that his experience there was one of the high points of his life. The terms of his service didn’t allow the secret agent to clear up the matter for many years after the war. A long-overdue knighthood came in 1970.

Coward might have settled back into the golden sunset of retirement, but he kept working for the pleasure he took in it. Active engagement in the theatre led him to criticize a younger generation of British playwrights, the “Angry Young Men” or “Kitchen Sink” leftists that included John Osborne and Arnold Wesker, with whom he nevertheless eventually developed a friendly association. It took him years to accept that the Coward model of experience—worldly, “jagged with sophistication”—meant almost nothing to postwar British society. Nowadays, when the Angries and Kitchen Sinkers in turn seem dated, we’re better able to appreciate Coward’s enameled wit and well-phrased irony as a cultural artifact, worth studying as such. I keep expecting some Ph.D. candidate in gay studies to analyze the social forces that led a part of the gay sector, beginning in the late 19th century, to develop an æstheticized armor of sophistication as a defense against surrounding homophobia and to propagate it among the part of heterosexual society sympathetic to gay men. In the first category you have Henry James, Oscar Wilde, Max Beerbohm, Ronald Firbank, Marcel Proust, E. F. Benson, Carl Van Vechten, Virgil Thompson, Glenway Westcott, and, in their early phase, Isherwood and Auden.

Obviously, the list also includes Coward. On the other hand, he remained firmly in the closet all his life—which doesn’t mean he didn’t hint. When asked by TV interviewer Edward R. Murrow if he did anything to relax, Coward replied, “Certainly, but I have no intention of discussing it before several million people.” For worldly people of Coward’s era, sex was private, end of story. None of the letters collected in this volume is explicit about the bedroom, though they dance around the topic. It’s as though Coward decided to follow the rule that etiquette books always used to urge on nice young women: “Never put anything in a letter that you would be unwilling to have read aloud in a court of law.” Homosexual acts were criminalized in Britain until 1967, but the thaw made little difference to Coward, who, when asked why he didn’t announce his preferences publicly, said that there was really no need to, though just possibly “there are a few old ladies who don’t know.”

Given his conservative stance, there’s no surprise if Coward’s letters and his song lyrics include some stereotyping slurs applied to women, people of color, Jews (or “Jewesses,” to use a term he favored); but then white males both gay and straight get their knocks, too, so I guess you’d have to call it equal-opportunity bigotry, fairly mild for the period before the post-colonial consciousness-raising of the 1960’s and 70’s. Meanwhile, he’s satirical about England as well (in “Mad Dogs and Englishmen”):

It seems such a shame

When the English claim the earth

That they give rise to such hilarity and mirth.

Most of us agree that there’s an absolving aspect to humor; it functions something like a moral holiday and fairly soon gives way to seriousness and responsibility, once the party’s over. Coward was nearly always funny, through slapstick, irony, verbal ingenuity, satire, and philosophic wit. Maybe we don’t actually want to attend the “Marvellous Party” his signature song describes, but it’s amusing to read about the quintessential mad bash, a pleasant means of access to the cultural moment when London’s “Bright Young Things” of the 20’s were brandishing their cigarette-holders, jeering at fools, gulping down their sidecars, dancing to Dixieland jazz, making brittle comments about each other, and being frightfully advanced about sex.