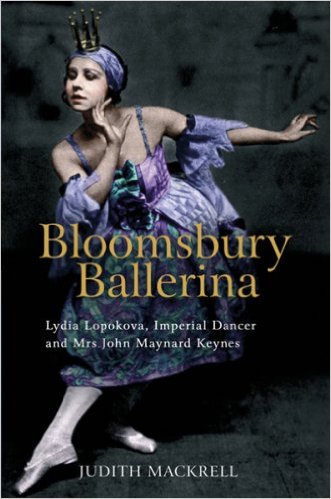

Bloomsbury Ballerina: Lydia Lopokova, Imperial Dancer and Mrs John Maynard Keynes

Bloomsbury Ballerina: Lydia Lopokova, Imperial Dancer and Mrs John Maynard Keynes

by Judith Mackrell

Weidenfeld & Nicolson

476 pages, £25.

LYDIA LOPOKOVA is not a name that comes to mind when one thinks of Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, which is celebrating the 100th anniversary of its founding this year. Bloomsbury Ballerina, a superb new biography by British dance critic Judith Mackrell, should help remedy this situation.

Lydia Lopokova’s father, a theater usher in St. Petersburg and a bit of a culture vulture, tried to put all five of his children on the stage, and all but one (who became an engineer) had a noteworthy career in ballet. As a twelve-year-old student at the Imperial Theatre School in St. Petersburg, Lydia was presented to Tsar Nicholas II after having danced Clara in the Nutcracker. She appeared to have been born to dance, both physically and emotionally.

Diaghilev has been quoted as saying in the late 19th century, “Europe needs our youth and our spontaneity; we must show our all.” He hired Mikhail Fokine of the Imperial Theatre School to choreograph Nijinsky, at that time Diaghilev’s protégé and lover. By the time the company arrived in Paris, in 1910, Lydia, the youngest member of the company, began “to move tickets almost as fast as … Nijinsky.” She was praised for her subtlety of expression, vitality, and grace. But she was not, says Mackrell, a Pavlova, naturally suited to the “grand classical roles. … She might be a captivating instrument for Fokine’s poetic imagination, but she was not, and never would be, an ideal Sleeping Beauty or Swan Princess.” The Ballets Russes made a number of Atlantic crossings, even during the treacherous days of World War I, bringing what was then called “toe dancing, ballet or ocular opera” to an America that had little experience with this art form. The Ballets Russes’s reputation for “impressionistic paganism” and “discordant energies” needed astute marketing, and “Lydia’s mollifying image” helped smooth their way. In 1918, when she arrived in England, she was hailed by critic Osbert Sitwell as “the revelation” of the season. He called her “the personification of gaiety and spontaneity and of that particular pathos which is its complement.” Early in her London career, she realized that her characteristically untidy dressing might be put to good use. When she stage-managed her own wardrobe malfunction and had to toss an item of underwear backstage, she put herself on track for legend status. It was probably through fellow Bloomsbury circle member Osbert Sitwell that John Maynard Keynes met Lydia. Apart from a couple of dalliances with prostitutes, the famed economist was a gay man; and Lydia Lopokova, a sophisticated young woman, was the veteran of a few heterosexual love affairs. Keynes, who was attracted to the famous, carried out love affairs with men ranging from Duncan Grant (the unmarried partner of Virginia Woolf’s sister Vanessa Bell) to W. J. H. “Sebastian” Sprott. (In the 1930’s, Sprott translated Freud’s New Introductory Lectures on Psychoanalysis, first published by the Woolf’s Hogarth Press.) Judging by the exchange of letters between Lydia and Keynes, it sounds like they were both having a wonderful time exploring varieties of intimacy, with Lydia wearing men’s clothes from time to time. Lydia and Maynard : The Letters of Lydia Lopokova and John Maynard Keynes (1989) contains most of the letters from which Mackrell excerpts, and also has a helpful glossary of names. But Sprott and Keynes, encouraged by their mutual friend Lytton Strachey, were still involved, and the triangle became increasingly trying for Lydia. By 1925, Sprott transitioned from lover to friend and Keynes didn’t try to find a “serious” replacement for him. Lydia and Keynes married that same year, and by all accounts it was a loving and devoted relationship. The major players in the Bloomsbury circle do not come off particularly well in Mackrell’s account. Despite the fact that he helped subsidize Duncan Grant’s and Vanessa Bell’s art and was godfather to their daughter, Keynes was not completely accepted. Apparently he was not high-class enough. Also, Vanessa felt that Lydia was “manipulating [Keynes] into marriage,” so Lydia was condescended to and treated with fairly overt cruelty—Lytton Strachey called her a “half witted canary”—even as her lack of Englishness grated on their sensibilities. Still, for years she and Keynes lived either in the same building or immediately adjacent to most of the members of the Bloomsbury circle. Critics differ in their estimates of the extent to which Lydia served as the model for the character of Rezia (wife of Septimus, who takes his own life) in Mrs. Dalloway (1925), with Mackrell concluding that the similarities were many. Apparently, Lydia was unaware of this, even after she read the book. Lydia, who also acted occasionally, gave her last public performance in 1939. It had become a full-time job to care for Keynes, who died in 1946. His death was no doubt hastened by physical and emotional exhaustion, first in 1919 at the Paris Peace Conference, then later as Vice President of the World Bank, where he attempted to negotiate favorable conditions for a loan agreement between the U.S. and Great Britain. Lydia lived on for thirty-five more years, until 1981, but her life was a sad downward spiral. Skeptical of postwar ballet, her living conditions and personality became increasingly eccentric, and she “guarded her privacy but also sealed her obscurity.” Mackrell, with her insider’s knowledge of ballet and theatre, lovingly recreates Lydia’s many worlds, from early-20th-century Russia, through the turmoil at the Ballets Russes, which Lydia left and rejoined several times. Included are many wonderful anecdotes from the world of dance, such as Nijinsky’s “habit of taking his supporting hand away in the middle of an arabesque,” which was thrilling to the audience but frightening to the ballerina. While most of the Lopokova family’s papers were lost during World War II, Mackrell had access to a vast trove of letters at King’s College Archive in Cambridge. The unpublished diaries and other primary sources that she was able to consult help keep speculation, other than questions of Lydia and Keynes’s love life, to a minimum. Bloomsbury Ballerina is also full of wonderful images and photographs, including Vanessa Bell’s drawing of the couple dancing the Keynes-Keynes, a duet that Lydia choreographed to parody the can-can.