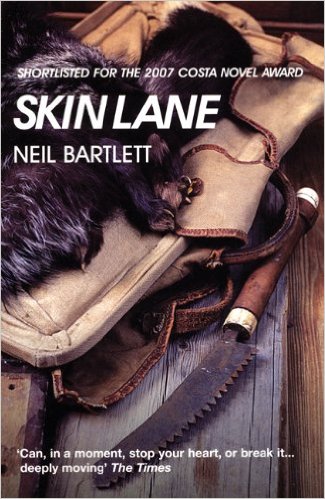

Skin Lane

Skin Lane

by Neil Bartlett

Serpent’s Tail

344 pages, $14.95 (paper)

IN HER REVIEW of Neil Bartlett’s Ready to Catch Him Should He Fall, Ruth Rendell asked, in amazed admiration, “If he can do this with his first novel, what heights will his fourth or fifth reach?” There’s no need to wait that long. Bartlett’s third novel, Skin Lane, is the astonishing equal of that first astonishing book.

Skin Lane, set in 1967 London, centers on Mr F, as the book calls him, a 46-year-old man who is a cutter at a furrier’s. His solitary, regimented life is disturbed by a recurring dream of a dead, dark-haired, white-skinned boy hanging in his bathtub. It is disturbed further when he finds the fulfillment of this dream in his boss’s nephew, a sixteen-year-old, dark-haired, white-skinned boy whom he is to train in the furrier’s trade. The novel tracks, almost moment by moment, Mr F’s seismic awakening into desire, obsession, and unrequited love. It is a harrowing experience, for Mr F and for the reader.

In Ready to Catch Him, Bartlett created a highly stylized world in which a boy named Boy is courted by and married to an older man, named O for Older, in a bar called The Bar watched over by Madame. The allegory turns the action into ritual and ceremony as enacted by archetypes. Bartlett’s second novel, The House on Brooke Street, was as resolutely realistic as the first was stylized, with interwoven narratives embedded in the London of 1923 and 1956. Skin Lane, in turn, miraculously combines the realistic and the stylized. Every detail has a basis in the realistic narrative and setting, but also seems to swell with significance, as in a dream, simultaneously mundane and other-worldly. There are, for example, narrative-based reasons for the main character to be called Mr F (for Freeman) and for the boy to be called Beauty (his name is Scheiner, and the girls at the furrier’s call him “Mr Schein,” or Beauty). But the constant use of the name “Mr F” makes the man seem like someone in a case history, and Beauty becomes the archetypal object of desire. Bartlett even offers the story as a version of Beauty and the Beast, with the fairy tale beast hovering above the realistic narrative of Mr F’s bestial desire and brute animal suffering.

Bartlett wields this realistic/symbolic style to produce an excruciating dissection of desire and love. Mr F’s utter nakedness, his helplessness and confusion about what’s happening to him, become almost intolerable, even as we remain bound to him with awe and pity. The book’s pace is glacial, which is part of its power: every movement of Mr F’s body and psyche is revealed and anatomized, with utter clarity and complete sympathy. It is not a coincidence that Bartlett has translated Racine: like Phèdre, Mr F is invaded by a forbidden love that he initially resists but that finally vanquishes him, a tale Bartlett reveals with Racinian precision.

Bartlett seems specifically drawn to forbidden love. Although Ready to Catch Him is deliberately vague about when it takes place, its ambiance feels pre-liberation. Brooke Street is partly set in the repressive 1950’s. Bartlett sets Skin Lane in 1967, the year Britain decriminalized homosexuality between adults: “Just a mile upriver, while our Mr F was leaning against his baking warehouse wall with his eyes screwed shut and imagining in vivid detail what it would be like to hold a naked young man in his arms, the House of Commons was beginning a debate on just that very subject.” But this theme is just the hint of a possibility here. Mr F’s story is not a triumphant coming-out, not an allegory of gay liberation. His desire for Beauty grows in a hothouse of suppression and sublimation, and especially of isolation: “He had to fight this battle on his own. This was, after all, in another time, almost in another country—and besides, don’t we all have to fight this battle on our own? When the knife strikes, none of us knows anything.”

Where Mr F experiences isolation, the reader may feel claustrophobia. Once Mr F has his dream, everything in his world becomes charged with sexuality. The animal skins that are his daily work possess a violent sensuality, blending beauty and death: as Mr F tells Beauty, “the most important thing in this business is choice of skin.” The master–apprentice relationship has a sexual dynamic. Mr F teaches Beauty to match skins for a coat by first touching and stroking them: “The boy hesitated, unsure—and quite without meaning to Mr F started muttering at him Touch; come on, touch it; but the boy still didn’t move.” Touch it—it’s what Mr F does every day, expertly, with skins, what he discovers he wants to do with Beauty’s skin, and what he realizes he dare not do.

To get a sense of the intensely sexualized world Bartlett has created, take an early scene, before Mr F has seen Beauty, while he is still puzzling about the dead young man in his dream. He goes to the National Gallery and is seized by a painting of Jesus and Thomas: “He wonders if Jesus has just said something to St Thomas—if he’s just said, for instance, very gently, It’s alright, you can touch me if you want to.” Mr F is taken by “the way you could tell he was insisting that the other man push his finger right inside, so far in that the skin around the edge of the wound was just beginning to pucker.” He “wondered how it would feel to do that; wondered if, when you touched somebody like that, he would feel cold or warm. Thinking about the young man in his dream, he wondered if he would still be warm. Inside.” Bartlett’s absolute narrative control lets him weave together a gently sexual Jesus, the brutally sexual detail of the skin puckering around the finger penetrating the wound, and Mr F’s heartbreaking attempt to imagine what it’s like to be “inside” the man he has seen in his dream. All this sexual tension with no explicit sexual content—that’s the world that surrounds Mr F once the dream has awakened his desire, and the world in which Bartlett suspends the reader.