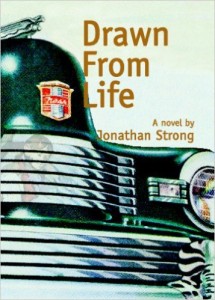

Drawn From Life

Drawn From Life

by Jonathan Strong

Quale Press. 294 pages, $17.

JONATHAN STRONG is a Boston-based author with close to a dozen novels and short-story collections to his credit. At the age of 24, while a senior at Harvard, he made a name for himself with his first collection, Tike and Five Stories (1969), garnering numerous national prizes and a comparison to J. D. Salinger. Drawn from Life is a quiet, subdued reflection on a gay character named Peter Dabney, whose inner life is filled with emotional turmoil even if all appears calm on the surface. Born in the mid-1940’s in the Midwest to a proudly liberal and non-religious middle-class family, Peter spends his childhood obsessed with cars, and his superior talent in drawing them leads to a career in art. In an unusual, unexpected, and timely coincidence, some of those very cars appeared in the Postal Service’s “50’s Fins and Chrome” commemorative stamp series at the end of 2008.

This is in many ways a coming-out novel, written in an unadorned style with a deliberately limited vocabulary forming short, mostly declarative sentences. In the opening pages, when young Peter says he doesn’t want his family to be like other families, his parents wonder why he’s “so fascinated with the unpopular and the neglected.” At this point the reader may expect that some sort of wild future lies in store, but such a life does not materialize. Peter’s school days are fairly uneventful, and he doesn’t seem terribly conflicted about his gay sexual orientation, identifying with Sal Mineo and James Dean: “he imagined being Sal Mineo driving very carefully around Los Angeles in an Airflow DeSoto with James Dean beside him. He was aware that he could never tell these secret stories … to anyone.” He has a fair number of uncomplicated sexual encounters with other boys after school and at summer camp, and one amusing adventure ensues when he translates some bawdy poems, found in the works of the modern composer Carl Orff, from Latin to English. Not surprisingly, perhaps, Peter winds up at Harvard, where he studies art history. He lives in Cambridge for a while after graduation, but by the end of the novel he’s moved into his late grandmother’s home on the Mississippi River, not far from an area known as Quad Cities, where he meets an ex-con, Wilfy, who was a small-town hood in his youth, and they settle into a life together. While Peter’s life is full of potential threats, he appears to have skirted them. Strong tantalizes us with the expectation that something awful will happen. Will Peter’s younger brother turn out to be homophobic? Will Peter follow his psychiatrist’s advice and marry a woman (on the comparatively progressive theory that homosexuality was not an illness but “arrested development”)? Will he be drafted into the Army and have to flee to Canada to avoid going to Vietnam? So far so good. Even when AIDS strikes in the 80’s, he and his lovers all avoid succumbing to its tragic grasp. Will he find an exciting adventure in Europe when he finally gets around to going there to visit a few selected art museums? Alas, no, but he spends hours enraptured by the paintings, particularly those by Cézanne. Will his relationship with Wilfy be sustained? Other than sex, they seem to have very little in common. Are Peter’s art gallery, his art classes, the vintage cars that he collects and then paints, going to lead to a retirement-age discovery? Chances are they will not. While Drawn from Life is a fast read, the atmosphere of sadness that Jonathan Strong has created lingers even after the book is closed.