SIX YEARS AGO, I began working on an anthology entitled Pulp Friction, which started out as a lighthearted look at the pulp novels of the 1950’s and 1960’s. While Pulp Friction was never intended to be a throwaway book, I originally envisioned it as a nostalgic walk through what I imagined to be a world of outdated and—to our eyes now—probably simpleminded, even homophobic fiction. Sure, the old covers, with their garish colors, lurid images, and often suggestive tag lines—“A Surging Novel of Forbidden Love,” “The Story of Men Who Don’t Belong”—were fun when reproduced as refrigerator magnets, but it was hard for me to imagine the books as literature. And it was almost impossible to think that they were not relics from some far-distant, queer-hating era nearly obliterated by the truths of Gay Liberation. I could not have been more wrong.

I began considering what I would include in Pulp Friction by looking through my own fairly extensive collection of older gay novels and soft-core porn novels from the 1960’s and early 1970’s. My plan was somewhat unformulated. I knew there was a difference between a novel like Michael De Forrest’s The Gay Year, published by Woodford Press in 1949 (which I had in a 1967 Lancer paperback reprint), or Harrison Dowd’s 1950 The Night Air (Dial Press), on my shelf for years in its  first 1951 Avon paperback printing), and a 1967 soft-core porn novel like Gay Whore by Jack Love (probably not his real name), issued by the French Line of Publisher’s Export Company, one of the most prolific producers of porn in the mid-1960’s. Clearly The Gay Year and The Night Air aspired to be literary novels; Gay Whore aspired to, well, stimulate the reader in other ways. What connected these books in my thinking was that they were “pulps”—that is, they all had eye-catching covers and were published between the late 1940’s and some time before Stonewall.

first 1951 Avon paperback printing), and a 1967 soft-core porn novel like Gay Whore by Jack Love (probably not his real name), issued by the French Line of Publisher’s Export Company, one of the most prolific producers of porn in the mid-1960’s. Clearly The Gay Year and The Night Air aspired to be literary novels; Gay Whore aspired to, well, stimulate the reader in other ways. What connected these books in my thinking was that they were “pulps”—that is, they all had eye-catching covers and were published between the late 1940’s and some time before Stonewall.

I quickly discovered that what I had conflated as a broad genre of “pulp novels” was in reality a wide-ranging, extraordinarily rich, and extensive body of literature that existed before Stonewall and Gay Liberation. I also

I made lists of books that might fall into this category. Some of these—Gore Vidal’s The City and the Pillar (Dutton, 1948), James Baldwin’s Giovanni’s Room (Dial Press, 1956), James Barr’s Quatrefoil (Greenberg, 1950), Fritz Peters’ Finistere (Farrar, Straus, 1951)—were “gay classics” that I had read and even owned. But in my mind these were exceptions to the rule that there were almost no gay novels published before Stonewall, that what we call gay fiction really began with the Gay Liberation Movement. And certainly it was true that all the gay books published before 1969 were epitomized by self-hatred and ended in suicide, murder, or some other form of death. I had repeated this truism in articles, even in my first book, Culture Clash: The Making of Gay Sensibility (1984).

I sought out books published by mainstream houses before Stonewall, finding mentions of titles in both bibliographies that specialized in gay titles as well as those who just covered postwar fiction and in used-book catalogues. I looked at the books advertised on the flyleaves of paperbacks from the period: these “Other Books You May Enjoy” served as short bibliographies of more queer books. While the last page of the Avon edition of Thomas Hal Phillips’s The Bitterweed Path (Rinehart Press, 1950) recommended novels by Christopher Isherwood and Truman Capote, the last page of later editions of Isherwood’s Mr. Norris Changes Trains listed Philip Wylie’s The Disappearance, and the end pages of Willard Motley’s Knock on Any Door (1947) listed Louis Bromfield’s Mr. Smith (1951) and Theodora Keogh’s The Double Door (1950). Blurbs were often an indicator of queer content. I found what I took to be a dubious reference in the 1950 Book Review Digest to gay male content in A Long Day’s Dying (Knopf, 1950), the first novel by Frederick Buechner, who is now a married Episcopalian priest and popular theologian as well as novelist. But when I found a copy of the book I saw that it was blurbed by John Horne Burns, Isabel Bolton, Christopher Isherwood, and Carl Van Vechten—a veritable index to the mid-20th-century queer literary scene. Within a few months, I had complied a list of over 200 novels from mainstream publishers that contained central or substantial gay male content.

Of course, not all of these novels were new to me. Works such as Carson McCullers’ Member of the Wedding (Houghton, 1946) and Reflections in a Golden Eye (Houghton, 1941) were (and are) still in print and highly regarded by both readers and critics. The same is true of Charles Jackson’s The Lost Weekend (Farrar, Rinehart, 1944) and Truman Capote’s Other Voices, Other Rooms (Random House, 1948). But they were merely the tip of a large iceberg of gay male writing that had virtually disappeared from view. It became apparent that these well-known books were part of a complex, widespread postwar gay male culture and tradition, a tradition that is sometimes acknowledged by the queer community but overwhelmingly ignored by mainstream critics and literary historiographers. Indeed, knowing that Other Voices, Other Rooms was one of at least six books with gay content published in 1948—preceded by five titles the year before and followed by seven titles a year later—places Capote, his novel, and his career in a whole new context.

The more pre-Stonewall novels with gay male themes published by mainstream publishers I found, the more I discovered honest, artistic attempts to portray gay male lives, written for what I assume was a diverse readership. My first thought was that these publishers had stumbled upon what we would now call a “gay market,” but after checking contemporary reviews of the titles—many of them reviewed positively and often in venues such as The New York Times, The Washington Post, The Los Angeles Times, Time, and The Nation—I found that they were aimed at a heterosexual audience. Clearly, they were read by gay men as well, but what was most startling to me was that from the late 1940’s to the early 60’s there was a lively public discourse about homosexuality taking place in popular reading culture. While some of the copy on the dust jacket of the cloth editions (and on the covers of the paperbacks) betrayed negative attitudes toward homosexuality, the books themselves were largely nonjudgmental and even sympathetic. It became clear to me that these novels were part of a public conversation about homosexuality that was going on in popular culture.

In this conversation, these novels, which neither virulently condemned homosexuality nor demanded its punishment, were counteracted by the plethora of scandal and crime magazines that were also popular during these years, such as Confidential and Exposé. These publications, which were read by far more people than the novels, consistently portrayed homosexuality in a negative light. But the content of the novels—even when they were marketed with cover graphics and copy suggesting that all gay men were lonely and sad—generally appreciated the nuances of sexuality and conveyed to its readers a mostly accepting attitude. While this sounds contradictory, I began to see it simply as another example of how popular culture was a fertile ground for the complicated discussions that were occurring about sexuality in the 1950’s and early 60’s.

TAKE WILLARD MOTLEY, an African-American writer from Chicago whose first novel, Knock on Any Door (Appleton, Century-Crofts), became a national bestseller in 1947. Critics and readers hailed the book as a masterpiece, and Motley was the subject of features in Life and other national magazines. These days, Knock on Any Door is hardly remembered except for the tepid, overly schematic 1949 Humphrey Bogart movie based upon it. But Motley’s book is a sprawling urban saga that compares to works by Theodore Dreiser or James T. Farrell. Its protagonist, Nick “Pretty Boy” Romano, is not only a hood but also a hustler who has sex with men for money and whose most sustained relationship is with Grant Holloway, a gay man who’s the moral center of Motley’s story. Motley went on to write three more novels—We Fished All Night (Appleton, Century-Crofts, 1951), Let No Man Write My Epitaph (Random House), Let Noon Be Fair (Putnam, 1966)—with some gay content, his final book dealing with, among other things, intergenerational sex. But Motley is mostly forgotten these days except by academics working in urban or African-American studies.

The disappearance of Motley from the popular imagination is not that surprising. Most American writers, however successful, eventually fade from view. Stuart Engstrand, once very popular, is known for his 1946 novel Beyond the Forest, the basis for the 1949 Bette Davis movie of the same name, famous now primarily for Davis’ line, “What a dump.” In 1947, Engstrand published The Sling and the Arrow (Creative Age Press), detailing the life of Herbert Dawes, a designer of woman’s clothing, and billed on the cover of the first edition as “The Strangest Story of a Marriage Ever Told.” Engstand brings us into the inner world of a man who would now be considered transgendered. His prose and plotting are hardly top quality (we know we’re in trouble when Dawes insists on dressing his wife in boyish clothes and then becomes obsessed with the Coast Guardsman with whom she’s having an affair), but the material is original, compelling, and startling.

For gay men today, not knowing about The Sling and the Arrow is not a terrible loss, but the absence of Lonnie Coleman’s 1959 novel Sam (McKay), about a gay man in publishing with a healthy attitude about himself and his sexuality, is. Coleman began his career in 1944 with Escape the Thunder (Dutton). In the next few years, his reputation grew and he became known as a major postwar Southern writer who dealt strongly with race relations and did so with enormous empathy. In 1955, he published Ship’s Company (Little Brown), a collection of stories, two of which had overtly gay and lesbian themes. One of the pivotal scenes in Sam takes place in a gay bathhouse where Sam meets his new lover, a nice doctor, to replace the conniving, career-climbing actor he was living with when the book began. Coleman didn’t disappear completely: starting in 1973, he published (with Doubleday) a trilogy of bestselling novels, a Civil War family saga, that became a TV miniseries. He died in 1982, his legacy as a major pre-Stonewall gay writer forgotten.

As I was researching these novels, I constantly had to rethink the history I had learned, and contributed to, since I came out. Something was wrong here. Why had I never heard of so many of these books? I spent much of my youth, even my preteen years, browsing bookstores, looking at paperback racks in drugstores, scouring used-book stores for “interesting titles.” I may have been twelve, but I knew what I wanted. How did I miss these books? Many of the titles I found during my research were Avon and Signet paperbacks commonly available in drugstores and bus stations when they were first published. I’d worked in my town’s public library when I was in high school; some of these books must have been there as well. I wasn’t blind or unaware. I found John Rechy’s City of Night when it was published by Grove in 1963, and read James Baldwin’s 1962 Another Country a year or so after it first appeared—both national bestsellers.

In the decades after Stonewall, some scholars began looking at homoerotic themes in such American writers as James Fenimore Cooper, Herman Melville, Mark Twain, and Henry James. Actually, critic Leslie Fiedler had broken this ground in his 1948 essay “Come Back to the Raft Again, Huck Honey,” and further explored these themes in his controversial 1960 book Love and Death in the American Novel (Stein and Day). There was interest in the idea of Oscar Wilde as a martyr to gay liberation and an exploration of how the novels of Ronald Firbank were a product of a “gay sensibility.” The posthumous publication of E. M. Forster’s Maurice in 1971 ignited discussion of a rediscovered gay male literary past, a great deal of it centering on Forster’s “closetedness” (for not publishing this novel, written in 1913–14, during his lifetime) or the low literary quality of the book. For the most part, however, post-Stonewall gay men—myself included—seemed to have little interest in rediscovering a more recent gay male literary past.

A great deal of this was, I believe, due to the need to believe in the myth that the Stonewall Riots and the emergence of a Gay Liberation Movement were a decisive break from the past and a radical beginning for a new future. While there was some enthusiasm for uncovering the history of British and German queer history—particularly that of Victorian London and Weimar Germany—gay liberationists had a blatantly dismissive attitude toward older homophile groups such as the Mattachine Society, SIR, and Daughters of Bilitis, and their publications. True, these novels, when published in pulp paperbacks, had cover illustrations of unhappy men wandering in a lavender fog, and tag lines such as “Lost in a Twilight World of Loneliness” and “The Shocking Story of Unnatural Love Between Men”—the nightmare embodiment of everything the post-Stonewall world imagined past gay life to be before liberation: sad, sorry, and sordid. There was no need to celebrate this past, and no emotional or psychic possibility for nostalgia or even camp enjoyment.

How wrong we were in those happy days of early gay liberation! As I found more and more novels to consider for Pulp Friction—I had room for only eighteen of them, and only a handful of those were literary novels—I was continually astounded by both their art and their content. Not all of them are great novels (although a good many stand the test of time), but all show us that during the postwar years, throughout the 1950’s and into the 60’s, homosexuality was not hidden or erased in popular culture. More important, it was not universally stigmatized and condemned. Indeed there was a visible strain of popular culture as embodied in these novels that promoted open discussion about homosexuality. This is not to say that there were not terrible repressive actions by government and the police, that there was not beastly violence directed against gay people, that lives were not ruined and people didn’t live in fear of exposure. But at the same time, there was a form of communal culture that embodied a very different reality.

THERE WERE at least six novels published in 1949, the year of my birth, that had central gay male content. Four of them—The Christmas Tree (Scribner), by Isobel Bolton (the pseudonym for Mary Brittton Miller); Stranger in the Land (Houghton, Mifflin), by Ward Thomas; Lucifer with a Book (Harper), by John Horne Burns; and World Next Door (Farrar, Straus), by Fritz Peters—were published by highly respected houses. They received numerous reviews in the mainstream press and were, one assumes, widely available. Don’t forget, in the postwar years there were many more independent bookstores than there are now; most department stores had very well-stocked book sections; and drug stores, stationary stores, as well as bookstores had “lending libraries” where you could borrow a new book for five to fifteen cents a day.

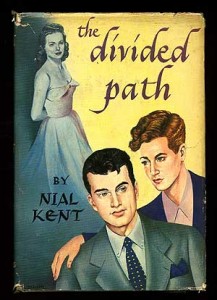

Along with these four titles two others were published: The Divided Path (Greenberg), by Nial Kent and The Gay Year (Woodford Press), by Michael de Forrest. Greenberg was located in New York and had a history of publishing titles with gay and lesbian content. In 1931 they published Andrew Tellier’s Twilight Men, and in 1933 they published an English translation from the German of Anna Elisabet Weirauch’s classic 1919 lesbian novel The Scorpion. Volume one was now titled The Scorpion and volume two, The Outcast; the first volume was translated by Whittiker Chambers. Greenberg would also publish James Barr’s Quatrefoil in 1950, and Donald Cory Webster’s groundbreaking The Homosexual in America in 1951. Woodford Press was named after Jack Woodford, a best-selling author of dozens of slightly risqué books that dealt with “adult” themes such as adultery, impotence, incest, and first sexual encounters.

So, of the six titles published in 1949, at least four would have been easily available to a wide range of readers—say, to my parents, who lived in Queens, New York, but spent most of their working and social lives in Manhattan. And if they had read these novels, what would they have learned about homosexuality? What images would they carry with them as it became clear to them—as it did when I was about eleven or twelve—that their oldest child was a homosexual?

Isabel Bolton’s The Christmas Tree is the story of Larry, a gay man who comes to his mother’s home to spend Christmas with Anne, his former wife, and their child. Anne’s new husband, an Army man referred to by everyone as “the Captain,” is also there, and after tensions inevitably mount, Larry kills his ex-wife’s husband by pushing him off a terrace. While Bolton spends a great deal of time explicating Larry’s relationship with his mother (what Diana Trilling rather inaccurately called in her March 19, 1949, review in The Nation “that most hazardous of themes, the sources of homosexuality”), the true theme of the novel emerges: the effect of the war upon masculinity. In the book’s closing moments, Larry’s mother thinks: “The Captain was a hero, a young man who had taken a more than honorable part in winning the war. There were many heroes in the world—millions of heroes in the world today. But who, he’d [Larry] seem to ask her again and again, could expiate the unutterable crime of putting into their innocent, their young and heroic hands, these satanic weapons, these infernal mechanisms they controlled.”

Trilling is correct in identifying the gay son–mother link in The Christmas Tree, but this relationship was a psychoanalytic trope in the postwar years, and I believe it was used by Bolton descriptively, not diagnostically. The same is true of Raymond Manton’s relationship with his mother in Ward Thomas’ Stranger in the Land, although he is more encumbered by his mother than Larry is in the Bolton novel. Something of a cross between Peyton Place and The Crucible, Thomas’ novel details the life of a 28-year-old homosexual high school teacher in the small town of Chatsworth, Massachusetts, who finds himself in the center of a police witch-hunt against gay men and is being blackmailed by Terry, his straight-trade, working-class younger boyfriend. Thomas has a high-end literary bent that, at times, becomes a trifle annoying, but he conveys with chilling accuracy the fear and terror of being exposed and humiliated (and jailed) for being queer. Hilda Osterhout, in her New York Times review of June 19, notes that “Ward Thomas is one of the first writers to deal with homosexuality, so recurrent a subject in modern letters, on a socially conscious plane as the problem of a minority ostracized by the group.” Indeed, this is Thomas’ major theme, remarkably political for its time. It would be another year before Harry Hay would articulate, in founding the Mattachine Society, that homosexuals were not malcontents and misfits but members of a distinct social and cultural group. But as dire as Raymond’s situation is, he refuses to crumble in its wake. Rather than give in to Terry’s increasingly impossible demands—a difficult situation, since Terry, for all of his bluster and hateful behavior, does have deeply fond feelings for Raymond—he murders him by drowning him in the local pond. This is no simple gay revenge triumph. As Bolton does with the murder of the Captain, Thomas complicates the situation noting that Raymond “killed his own soul when he killed the body of Terry Devine.”

It would be a mistake to see Thomas’ startling ending simply as a way to punish Raymond—resonant of Oscar Wilde’s “Ballad of Reading Gaol,” in which “each man kills the thing he loves”—as the political context of the novel makes it clear that this is also an act of resistance. Throughout the book, Thomas discusses the fate of the Jews in the Holocaust, mentioning Auschwitz specifically (probably one of the first mentions of the camp in a work of American fiction) as well as the political and social oppression of African-Americans in the U.S. In this context, Stranger in the Land makes a strong case for the need for a politics of group resistance for homosexuals.

World War II is also the backdrop for Fritz Peters’ The World Next Door, which details the mental state of David Mitchell, who has plunged into a state of psychosis. The novel is a bravura performance, written in the first person, that places us inside Mitchell’s consciousness as he gradually moves from psychosis to sanity. The book was widely praised—C. J. Rolo, in the November issue of The Atlantic, called it “brilliant, an astonishing piece of work,” and James Hilton in the September 18 New York Herald Tribune Weekly Book Review claimed it was “by any standards a notable piece of work.” Praise was forthcoming from the blurbers who included Alfred Kazin, Jean Stafford, and Eudora Welty. But what is not evident from the dust jacket is that David Mitchell’s problems are not only caused by the horrors of the war but by his not-so-repressed homosexual feelings.

Mitchell’s doctors think his homosexuality is the root of his problems (as does his own mother), but when asked about being homosexual, he claims he is not, although he has no problem admitting that he has slept with a man “because I was in love with him, that’s all.” Because the novel is written from inside Mitchell’s consciousness, he is what Henry James would call an unreliable narrator. On the one hand, it makes perfect sense for Mitchell to deny being homosexual in a 1949 mental institution—but to admit to sleeping with a man because you love him seems crazy. We’re never sure of Mitchell’s actual homosexual experiences—something did happen during the war, but Mitchell is quick to say “Oh, that! You don’t have to worry about that! There was a general who … tried to get funny, that’s all.” Merely broaching the issue of homosexuality in this manner is both brave and startling. Because of the shifting nature of The World Next Door’s point of view, we’re constantly challenged to evaluate how we view not only mental illness but homosexuality as well. The author’s biography on the dust jacket states that it’s “based on actual experience.” In 1951, Peters would publish Finistere (Farrar, Straus) about a sixteen-year-old American boy who has an affair with the physical education teacher at his French school.

As radical as Peters’ treatment of homosexuality was, reviewers didn’t find it all that threatening and saw no reason to dislike or mistrust the book. This was not the case with John Horne Burns’ second novel Lucifer With a Book. In 1947, Burns had published, to critical acclaim, a collection of interwoven short stories called The Gallery, which included “Momma,” set in an Italian gay bar during the occupation. Lucifer With a Book was set in a New England boys’ academy that rife with anti-Semitism, homophobia, and racism. While Guy Hudson, the novel’s protagonist—an army veteran whose face is disfigured from a war wound—is ostensibly heterosexual, the book is saturated with queer ambiance and innuendo, from students who have crushes on Guy to the instructors’ own active sexual life with “bed partners” of unspecified gender. Burns’ point in the novels seems to be to eviscerate almost all of post-war U.S. culture for its intolerance and stupidity.

As with Stranger in the Land, Burns’ political vision explicitly connects the mainstream culture’s hatred of sexual deviation with anti-Semitism and racism. Critics were looking forward to Lucifer With a Book as a continuation of his success with The Gallery. But, unfortunately for Burns, Lucifer was far too gay in plot and sensibility and the critics attacked. Maxwell Geismar, in the April 2 issue of The Saturday Review of Literature, put his finger on the fact that Burns’ hero was not convincingly heterosexual: “The central love affair of the novel, through which Guy Hudson finally realizes the difference between sex and love, is not convincing.” And Burns’ all-out attack on American mores prompted the reviewer in the June issue of Catholic World to note that “Mr. Burns has dipped his pen too deeply in gall,” adding, correctly, that “Krafft-Ebing, who is named only once, seems to have inspired the author frequently.”

These were the books that were published in the year I was born. They were available in bookstores, libraries and—when they were released in paper editions the year later—drug stores, bus depots, and stationary stores. These are all books that I have read in the past five years—well into my life as a gay man and a cultural critic. What would it have been like to have read them when I was thirteen, when I read James Baldwin’s Another Country, or fourteen, when I read John Rechy’s City of Night—both of them arguably less “positive” than any of these books from 1949? Would I have had a different understanding of what it meant to be gay? In retrospect, I think I had a fairly good understanding of my queerness in my teen years. I knew from Another Country that I wanted to move to Greenwich Village as soon as I was able, and City of Night told me that there were whole communities of men like myself out in the world. Sure, some of them were lonely, but some of them weren’t. I would have liked The Christmas Tree or Lucifer With a Book when I was thirteen or fourteen; I like them now. But what knowing about them when I was a teenager would have given me a far better sense of what gay life was like during the 1940’s. I think that means I also would have been less able to forget what had happened before me and, I hope, more humble about what I, and my fellow Gay Liberationists, were doing in 1969—a short twenty years after these six novels were published.

Michael Bronski, a lecturer at Dartmouth College, is the author of Pulp Friction (2003) and The Pleasure Principle: Sex, Backlash, and the Struggle for Gay Freedom

(2000).