FULL DISCLOSURE: I came of age in the 90’s and always thought of Bette Midler as that middle-of-the-road star of Beaches who sang the movie’s treacly theme song, “Wind Beneath My Wings.” Sure, she had her brassy broad routine, but this pseudo-outrageous, semi-tough-talkin’ persona seemed tailor-made for Middle America. So imagine my surprise when, a couple of years ago while writing a master’s thesis on Glitter Rock, I found nestled in the discussions of Lou Reed and Alice Cooper a reference to Bette Midler. What could this mean? Digging a little further, I soon came across this contemporary quote from Lester Bangs (Creem, August, 1973) that places her squarely—though not “squarely”—in the midst of the Glitter scene:

Despite lingering questions about her ability to cope with stardom—and choose material—she is definitely the Queen of the Glitter Hop. Squares compare her to Garland and Streisand, and hip folk love her for her Shangri-Las, Crystals, and Chiffons remakes. The gay crowd (hip and square) love her because she came out of the Baths, because she shares their affection for camp and kitsch, and because, above all else, they found her first. She proved that every time you thought they were singing about love, they were actually singing about sex.

A Stah Is Born

Bette Midler was born on December 1, 1945, in Honolulu, Hawaii, to Fred and Ruth Midler. Fred had ended up in Hawaii during World War II when he was in the Navy. Her first years were spent on a Navy compound, but the family moved to rural Aiea around 1952. While living in Aiea, the family was one of the few white, and definitely the only Jewish, family in the area, which was populated mostly by Hawaiians, Samoans, Chinese, Japanese, and Filipinos. It was growing up in this environment that Bette got her first taste of being an outsider.

Fred Midler had very specific middle-class values that he expected his household to abide by. His wife was expected to stay home and care for the house and the children, while his daughter was expected to be polite and chaste until growing up to marry a nice Jewish boy and make a family. But Bette had different ideas, as she later reported:

When I got very brave, I’d go out to the red-light district and walk around. All the sailors and people in the armed forces would go there to see a dirty movie or a bawdy show or to pick up a girl. It was a real red-light district and it was so wonderful! It wasn’t bullshit [like]42nd Street or Eighth Avenue in New York. It was for real opium dens and lots of Orientals! My mother was always trying to make sure that I wasn’t exposed to any of the seamier aspects of life. Consequently, I was always fascinated by the seamier aspects of life. That was the biggest influence on my life. I wanted to be with seamy people and be in seamy places.

Starting in elementary school, Bette began performing for her classmates in school plays and musicals. It turned out she had the ability to make people laugh when she performed, a talent which, when combined with her fascination with the seamier aspects of life, would prove pivotal to her later career.

In 1963 she graduated from Radford High and went on to the University of Hawaii, where she studied acting for two years. Her big break came in April 1965 when a Hollywood movie based on James Michener’s Hawaii was being filmed nearby. Bette landed a small part as a missionary’s wife. With the money she saved from playing this role, she managed to make her way to New York City.

Bette ended up renting a room in a seedy hotel called the Broadway Central. For the next couple of years she did some odd jobs (for example, as a go-go-dancer in New Jersey). Around this time she also became involved in New York’s underground theatre scene. This was an experience that would form a part of her underground alter ego, “The Divine Miss M,” in the early 70’s. The experimental theatre scene of the late 60’s revolved around directors like Tom Eyen and Charles Ludlum’s Theater of the Ridiculous. Experimenting with the boundaries of traditional theater and focusing on outrageous subject matter, these directors were part of the general revolt against 1950’s conservatism known as the Counterculture. Bette got two roles in the 1965–66 season, one in Tom Eyen’s Cinderella Revisited and the other in his Miss Nefertiti Regrets. Bette reminisced a few years later about her time in the Ridiculous Theatre scene: “That’s really my thing. I watch things, then I twist it around to get another view, then give it back to them and make them see it in another way that they never saw before ’cos they were so busy taking it seriously. I can’t take any of it seriously. That’s what I get from the theatre of the ridiculous—the sardonic side of it. What good is it if you can’t giggle at it, ’cos in the long run that’s all it is” (Zoo World, Oct. 25, 1973).

In 1966 she managed to get a small role in the Broadway smash Fiddler on the Roof. It was here that she would meet two men who would provide another piece in the puzzle that would ultimately make her an underground film star. The first  was a dancer in the play, Ben Gillespie, with whom she had an affair. He broadened her exposure to art and, more importantly, to music. At Gillespie’s suggestion she went to the library at Lincoln Center and started listening to old torch songs and blues recordings. The other man was William Hennessey, who got Bette to immerse herself in the old Hollywood movies of the 1930’s and 40’s, especially ones featuring the larger-than-life female stars of that era.

was a dancer in the play, Ben Gillespie, with whom she had an affair. He broadened her exposure to art and, more importantly, to music. At Gillespie’s suggestion she went to the library at Lincoln Center and started listening to old torch songs and blues recordings. The other man was William Hennessey, who got Bette to immerse herself in the old Hollywood movies of the 1930’s and 40’s, especially ones featuring the larger-than-life female stars of that era.

A very sad event furnished the final piece of the puzzle: the death of Bette’s sister Judith in 1968. Judith was in New York to see Bette in Fiddler when she was hit by a car backing quickly out of a loading dock. She was instantly killed. This situation threw Bette into a depression that lasted at least a year and perhaps much longer.

The person who emerged at the end of the decade was the product of these disparate and unusual circumstances: a girl who’d grown up in Hawaii as an outsider, fascinated by the tawdry or forbidden side of life, intrigued by the idea of challenging convention through performance in the underground theatre. She was attracted to the heart-wrenching songs of an earlier era and to the glamour of Hollywood in the 1930’s and 40’s. Now she harbored a deep sadness over losing her sister, a sadness that permeated aspects of her early performances. Those were the elements that would be combined in the persona that emerged in 1970 as the Divine Miss M.

In 1969 Bette had quit Fiddler and started singing at a Village nightclub called Hilly’s, and after that moved up to a singing gig at the Improv, a comedy club, where new singers were allowed to perform in between the comedy acts. It was at this time that the owner of the Improv, Bud Friedman, caught a rendition of “Am I Blue” which so stunned him that he took Bette on as her manager for a year. He immediately got her bookings to sing on two daytime TV talk shows, those of Mike Douglas and Merv Griffin.

In the summer of 1970, Bette got a call from Bob Ellston, a vocal coach with whom she had studied in Manhattan. This was to prove one of the most important breaks of her career. What Bob said was, “Listen, I know this guy who runs a steam bath and it’s a very popular place for homosexuals to go and gather, and he’s looking for entertainment. Would you like to work there?”

The Continental Bathhouse

In order to place Bette Midler at the Continental Baths, we have to understand the history of gay baths generally in New York and the Continental Baths in particular. Bathhouses had existed in large urban areas of the U.S. since the 1800’s at a time before indoor plumbing. They afforded the masses a place to wash and relax in a safe atmosphere. Baths had been very common in ancient times throughout the Roman Empire and were sites of sexual liaisons and prostitution, a tradition which wasn’t entirely lost in the bathhouses of America. By the 1890’s, certain establishments in New York had become meeting grounds for homosexuals. By World War I, several of these had become institutionalized as gay bathhouses, notably the Lafayette Baths. After World War II, the city instituted a crackdown that lasted for about the next twenty years, an aspect of the overall cultural conservatism that marked this era. By 1967, what with indoor plumbing a universal amenity, there were only three bathhouses left in Manhattan: the Everard, the St. Marks, and the Mt. Morris. All three had a reputation for being slimy, smelly, and run-down—and homosexual in their clientele. Patrons would enter with their heads down and encounter rude, heterosexual front desk clerks before starting their search for a quick sexual encounter.

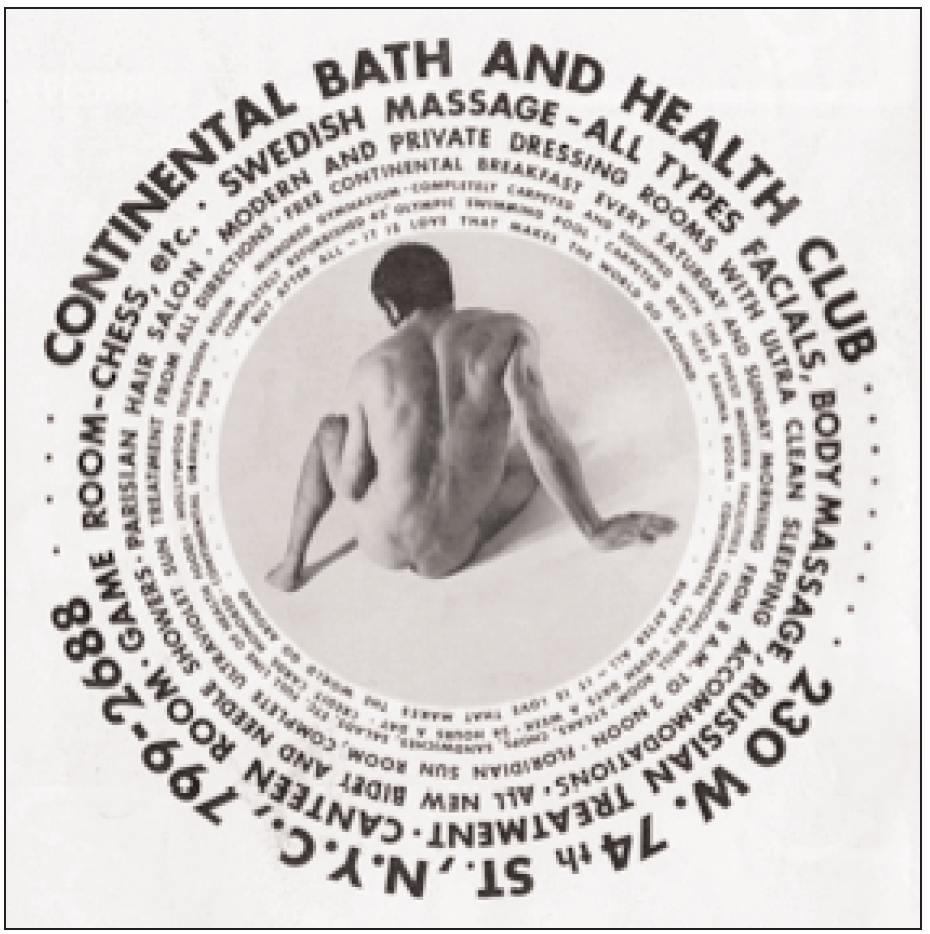

All this changed in 1968 when bisexual opera singer Stephen Ostrow decided to open a different kind of bathhouse, one that would be safe and clean and would treat homosexuals with dignity. Searching around New York he stumbled upon a health club in the basement of the Ansonia Hotel on West 74th Street close to Broadway. The Ansonia had been built at the turn of the century as an artists’ living space. By the 60’s the Ansonia was quite run down, as was the Upper West Side neighborhood where it was located. Close to the Ansonia were several welfare hotels, and crime in the building was a mounting problem. The health club in the basement had been unused for many years and was a complete wreck. Ostrow negotiated a five-year lease at a low price in exchange for fixing the place up. The next step was to court the emerging gay press. The newly formed Advocate, founded the previous year in Los Angeles—it would go national in 1969—and the New York-based Gay magazine agreed to offer coverage of the new establishment. This was unprecedented. The three old bathhouses shunned publicity and certainly didn’t take out ads in local gay papers, depending instead on word of mouth. What was amazing about the ads for the Continental was that they hid nothing—this at a time when everything gay was illegal. You could still be arrested for same-sex dancing, much less for public sexual behavior.

In July 1970 Bette Midler appeared at the Continental Baths for the first time. She contracted for an eight-week stay playing one show each on Friday and Saturday nights. Billy Cunningham, who had been a pianist with her at the Improv, would be her accompanist. The response to the first weekend’s performances were polite and restrained. This caused the two of them to go back and change the music to more upbeat numbers like “In the Mood” and “Chattanooga Choo-Choo.” She also started to work on incorporating comedy routines and banter into her act. This change in direction went over well, and by the end of Bette’s engagement she’d managed to convert many bathhouse customers into fans. An interview and profile appeared that October in Gay magazine. Also at this time she started to appear on The Tonight Show, hosted by Johnny Carson, where she would speak of singing in a “men’s health club.” Bette came back for another eight-week gig at the Baths from November 1970 to January 1971.

It was during this period of two years that Bette established herself as a phenomenon of gay culture and a permanent gay icon, melding vaudeville with high camp in performances that might include a riff as Carmen Miranda wearing a hat made of fruit or an appearance dressed only in a towel. As word of the show spread by mouth through New York and beyond, Bette herself was beginning to think of life after the Continental Baths. She ended up giving the first of several “farewell” performances (January 1971) that would crop up periodically over the next two years.

After her first farewell tour, she went on the road for a while. Her engagements included, among others, starring as the Acid Queen in the Seattle Opera Company’s production of Tommy and playing nightclubs in Chicago, notably at Mr. Kelly’s. It was during a performance in Chicago in May that she met an up-and-coming gay comedy writer named Bruce Villanch, who would become the writer of the comedy pieces that came between the musical numbers. Having Villanch as her writer led to a more polished comedic style and a more central role for comedy in her shows.

That September Bette tried to make her “straight” New York City debut by headlining at the Upstairs at the Downstairs. Her first night there she bombed, as the straight audiences did not connect with her material. At this point she turned to her old audience at the Baths and took out an ad for her next performance in the popular underground magazine Screw. She ended up packing the place with her old enthusiastic audience for this and subsequent shows. It was at one of these performances that the head of Atlantic Records, Ahmet Ertegun, saw her perform. Seeing the wildly appreciative response she received from the audience, he decided then and there to sign her.

By the summer of 1972 Bette was playing Las Vegas with Johnny Carson and selling out at Carnegie Hall. Her first album, The Divine Miss M, was released in November and it made it to #9 on the album charts. She even had a hit with the first single, “Do You Want to Dance,” making it to #7 on the singles charts. To coincide with her album debut, she made her final farewell appearance at the Baths. Steve Ostrow didn’t place limits on attendance, and the place was packed. With the heat and overcrowding, the performance was unpleasant for most everyone involved. With this, an era was over. Bette would continue to spend the 1970’s using gay humor and camp as part of her act, but by the 1980’s she had moved away and reinvented herself yet again. Indeed by 1980, as revealed in her autobiography Bette Midler: A View from a Broad, she was already trying to distance herself from her days at the Baths:

This is inevitably the first question in any interview, and even though I know it’s coming, I always wince when it lands. It gets very depressing, you know. I’m certain that whatever I may do in my life, whatever I may achieve, the headline of my obituary in the New York Times will read: Bette Dead. Began Career at Continental Baths. I will now say what I pray to God will be my final word on the subject. It was a great job and a great experience. I did not perform in the middle of a steam room but in the poolside cafeteria next to the steam room.

As if to circle the square—and perhaps we do mean “square” this time—Bette Midler has recently begun a two-year, 200-performance engagement in that glitter capital of the world, Las Vegas, but the glitter this time is far from the heady, edgy stuff of the Divine Miss M.

Jeff Auer is a public historian who teaches in the history department at the University of Nevada at Reno.