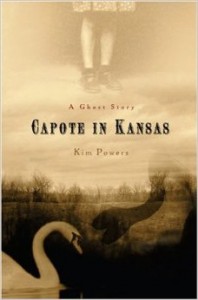

Capote in Kansas: A Ghost Story

Capote in Kansas: A Ghost Story

by Kim Powers

Carroll & Graf. 304 pages, $25.

FOR A TIME, Truman Capote was fading from our collective memory. When discussed at all, he was quickly and safely caricatured into a long scarf and a spoiled child’s voice, much in the way that Elvis became little more than his peanut butter and bacon sandwiches. True originals are manifestly threatening because they confound easy categorization and cannot be miniaturized to fit the needs of our media culture, itself sustained by that unsettling combination of adoration and jealousy. Occasionally, even genuine fans unwittingly contribute to their hero’s obliteration by flattening him with sentimentality and stereotype. Unfortunately, just such a disservice has been rendered to Truman Capote and his life-long friend, Harper Lee, by Kim Powers in his recent book Capote in Kansas, a fictionalized account of their relationship, including the time they spent together in Kansas investigating the Clutter murders, the subject of Capote’s most famous book, In Cold Blood.

Born in New Orleans in 1924, Truman Capote inherited his father’s hard drinking and his mother’s social ambitions, traits that would later prove lethal to Capote’s health and career. His mother’s departure from their small southern town to Park Avenue and a second husband might have worked out for young Truman, whose theatrical demeanor was well-suited for New York, but she left him behind—a rejection that was not lost on the child, who responded by escaping deeper into literary fantasy and a fragile grandiosity that never left him.

Capote’s first novel, Other Voices, Other Rooms (1948), made him famous at 24. His literary talent was all the more unusual for his relative lack of formal education. An indifferent student, he completed high school but never attended college and was never known to read much. (Gore Vidal remarked in his memoir Palimpsest that Capote was intellectually incurious.) At around this time, Capote formed a close relationship with literary scholar Newton Arvin. Their friendship was an intellectual revelation to Capote. Arvin introduced him to a wide range of ideas and filled in large gaps in his knowledge during their long conversations, which often lasted well into the dark nights at Yaddo in upstate New York, where they were both on writing fellowships.

A Tree of Night and Other Stories, a collection of short stories, was published to warm reviews in 1949, securing a position for Capote as a promising new stylist. Despite its tragic overtones, Capote’s life was also triumphant, and this should not be forgotten. He was brave and candid if not always truthful. He probed the darkest hearts behind the phony Pepsodent smiles of the 1950’s and 60’s, an era that was not known for candor in matters of sex and relationships. Capote’s very existence became a rebuke to the suffocating sexual mores of this era. For there he was, slugging it out on Johnny Carson’s sofa with the overheated macho stars of the day, defiantly lisping insults in any direction he chose. Capote was effeminate all right, but he had the courage to live with the consequences of his gay persona rather than hide in the shadows. Norman Mailer once called Capote “a ballsy little guy,” no small compliment from the late literary prizefighter.

Having died in 1984, Capote’s reputation was fading by the 1990’s. Then came the movies: Capote in 2005 and Infamous in 2006. Capote had finally achieved in death what had eluded him during the last twenty years of his life: a comeback. Directed by Bennett Miller and based on a portion of Gerald Clarke’s authoritative biography of the same name, Capote featured a dead-on, Oscar-winning portrayal of the author by Philip Seymour Hoffman. Infamous—directed by Douglas McGrath and based on George Plimpton’s Truman Capote: in which various friends, enemies, acquaintances, and detractors recall his turbulent career—although it suffered by opening so soon after Capote, provided a fascinating psychological examination of what led to Capote’s inability to produce another novel after In Cold Blood. It also included the lowdown on his struggle to complete Answered Prayers, his thinly disguised account of New York society that lost him friends and dinner invitations from Fifth Avenue to Fire Island.

Capote in Kansas, a novel written by Kim Powers, centers on ghostly visitations to Capote from the Clutter family of In Cold Blood fame. This was the family that was murdered by two young men who broke into their home ostensibly just to rob the place. Thus, for example, a ghostly Nancy Clutter, the daughter, angrily demands an apology from Capote for exploiting their tragic murder for his book. A writer for Good Morning America, Kim Powers is the author of The History of Swimming, a memoir centering on the trials of twin brothers growing up gay in a dysfunctional family. In Capote In Kansas, Powers turns his attention to Capote and Lee, who influenced and fascinated him.

The danger in fictionalizing people whose lives were already stranger than fiction is that their lives will be diminished rather than elevated. Alas, Powers is not able to harness Capote’s manic conversational brilliance. There’s no evidence of the well-timed riposte or gemlike anecdote about the famous at parties. Instead, Powers’ Capote is a frightened, weepy bore. But if Capote lacks sparkle, the other characters are even less engaging. Myrtle, the longsuffering salt-of-the-earth housekeeper, has all the complexity of a 1930’s MGM maid as she repeatedly reminds herself, “Only God knows what’s in the minds of white people.” She refers to Capote as “Mr. Truman”; at one point when they’re crouching next to a car (don’t ask why), Powers describes them as “Ebony and Ivory, propped up against the metal backrest of a rusted-out car, the dark sky and palm trees high around them.” And the clichés keep coming. When Capote and his friend and fellow writer Harper Lee are leaving a bar in Kansas, Powers adds: “Oh, this night was young, and cold; and there were places to see and miles to go before they slept.”

Harper Lee (“Nelle” to friends) is depicted as a Southern spinster who lives with her prickly, suspicious sister, also a spinster. Having written To Kill a Mockingbird and won a Pulitzer in 1961, she has accomplished nothing since. Powers raises the rumor that haunted the book at the time of its publication that its author was Capote rather than Lee. While this notion has been thoroughly discredited—Capote was never one to forego credit for anything he did—Powers presents it as a serious hypothesis.

There are few writers who are also public personalities these days, mostly because there’s no longer a public forum for them. It’s hard to imagine a literary feud on Jay Leno comparable to those involving Gore Vidal, Norman Mailer, and Truman Capote on Johnny Carson. For all this book’s faults, Powers must be thanked for reminding us of a time such discussion was still possible in the mass media, when a respectable gay man’s apartment looked more like that of Oscar Wilde than that of Pottery Barn, and when your destination after work was more likely to be the Russian Tea Room than your local gym.