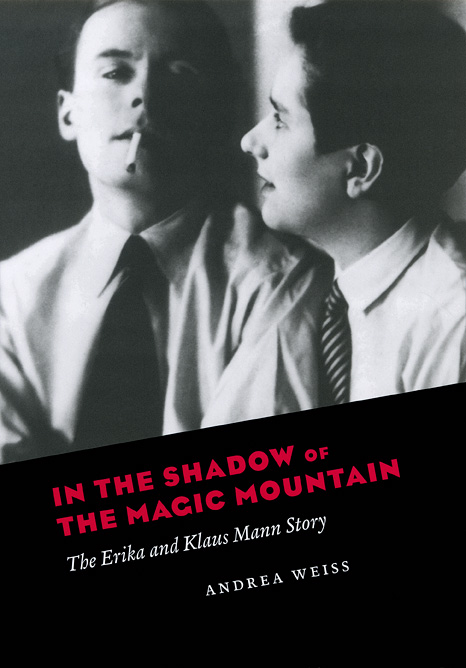

In the Shadow of the Magic Mountain:

In the Shadow of the Magic Mountain:

The Erika and Klaus Mann Story

by Andrea Weiss

Univ. of Chicago. 272 pages, $27.50

THE TWO oldest children of Thomas Mann, both born in the earliest years of the 20th century, were possessed of enormous intellect, charm, and charisma. They were openly gay in the case of Klaus, bisexual in the case of Erika; and they were decades ahead of their time. Although they began to drift apart in their early thirties, their lives had been deeply intertwined in ways that are apparent even to casual observers of photographs in their earlier years. Andrea Weiss, author of Paris Was a Woman (1995) and professor at CCNY, has done a tremendous amount of research using original resources in Munich, where the Manns were born and grew up, interviewing relatives, lovers, and friends, many of whom were able to enumerate instances of the siblings’ emotional, if not physical, incestuousness.

Erika and Klaus’s adult lives began when they arrived in Berlin in 1924; they were eighteen and seventeen years old and fully confident of their talents. Erika started to make her way by acting, Klaus by writing. Klaus’s first novel, The Pious Dance (1925) can, as Weiss states, be read as a coming-out novel. He dedicated it to Pamela Wedekind, with whom Erika had developed a relationship. Pamela was the daughter of playwright Frank Wedekind, who wrote the 1903 play on which the current Broadway hit musical Spring Awakening is based. Erika began to build a career in the theatre, playing small parts while touring in the provinces. She also started writing in a variety of genres, including children’s books, plays, and magazine articles. She and Klaus traveled widely on both sides of the Atlantic, sometimes with the small anti-Nazi literary cabaret called The Peppermill that Erika had put together in 1933. Erika wrote the songs, whose lyrics, according to Weiss, are virtually untranslatable, “so riddled are they with oblique attacks on the Nazi regime, hidden in innocent fairy tales and droll cabaret skits.” Klaus and Erika’s dual autobiography, Escape to Life (1939), states that they gave 1,034 performances before closing the show in New York in 1936. English lyrics had been written, some by W. H. Auden, who had gallantly married Erika to give her British citizenship. In 1936, Klaus published his best-known novel, Mephisto: The Story of a Career, in part a roman à clef about the actor Gustaf Gründgens, who’d been one of Klaus’s lovers before Gustaf married Erika. They divorced in the late 1920’s.

Klaus tumbled from affair to affair, always supported by an allowance from his parents. His hard drug habit waxed and waned throughout his life, yet his literary output was of high quality, and the literary magazines he cobbled together drew contributors such as Gide and Huxley. He was at his healthiest when serving in the U. S. armed forces during World War II. Both he and his sister had an almost childlike belief in the best aspects of American democracy and worked hard to be able to enlist, serving as writers and translators. Their ardently anti-fascist and anti-Nazi views, nurtured as early as 1927, had led to their subsequent harassment by the Nazis when still in Germany, as did the Jewish lineage of the Pringsheim family. They and their parents—who’d fled to California after having relocated to Switzerland at the beginning of the war—were hounded back to Europe after the war by the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), whose members had branded the Manns as “premature anti-fascists.”

While repetitious at times, this dual biography gives a fascinating glimpse into the two Manns’ eventful and celebrity-filled lives. Andrea Weiss’s access to some of the most intimate writings by Klaus (who died by his own hand in 1949) and Erika (who, though she lived twenty years after her brother, never recovered from his death) lends real depth, and her vivid descriptions of many of the Manns’ works of fiction and nonfiction—daughter, son, and father—will send readers in search of some of these classics.