THOSE OLD ENOUGH will recall the classic photograph of the blond young man sticking flowers into the rifle barrels of soldiers who were there to defend America against the hippies who had vowed to levitate the Pentagon in a massive demonstration in October 1967. The young man was George Harris III, who went through many transformations before his death from AIDS in 1982. Not long after the Pentagon demonstrations, Harris could be seen dancing with inexhaustible energy, as if in a dervish-like trance, on the green fields of rock concerts in Golden Gate Park in San Francisco. His wardrobe and demeanor in those years was beyond “drag”: sporting beard and moustache, he was more like the village magician, covered in beads and bones, feathers and fur, sparkle and mascara. He had become Hibiscus and would go on to found the Cockettes, a drag troupe that was popular in the late 60’s and early 70’s.

Terms like “gender-bending” or “drag queen” don’t begin to describe the Cockettes, who emerged at the end of the 1960s at the old Palace Theater in North Beach, San Francisco. Thanks to the 2002 feature-length documentary, The Cockettes, directed by David Weissman and Bill Weber, that special moment in gay history has been saved from oblivion. While the film offered a behind-the-scenes look at the Cockettes, it did not focus on the shows from the audience’s perspective, as footage of the actual shows was not available.

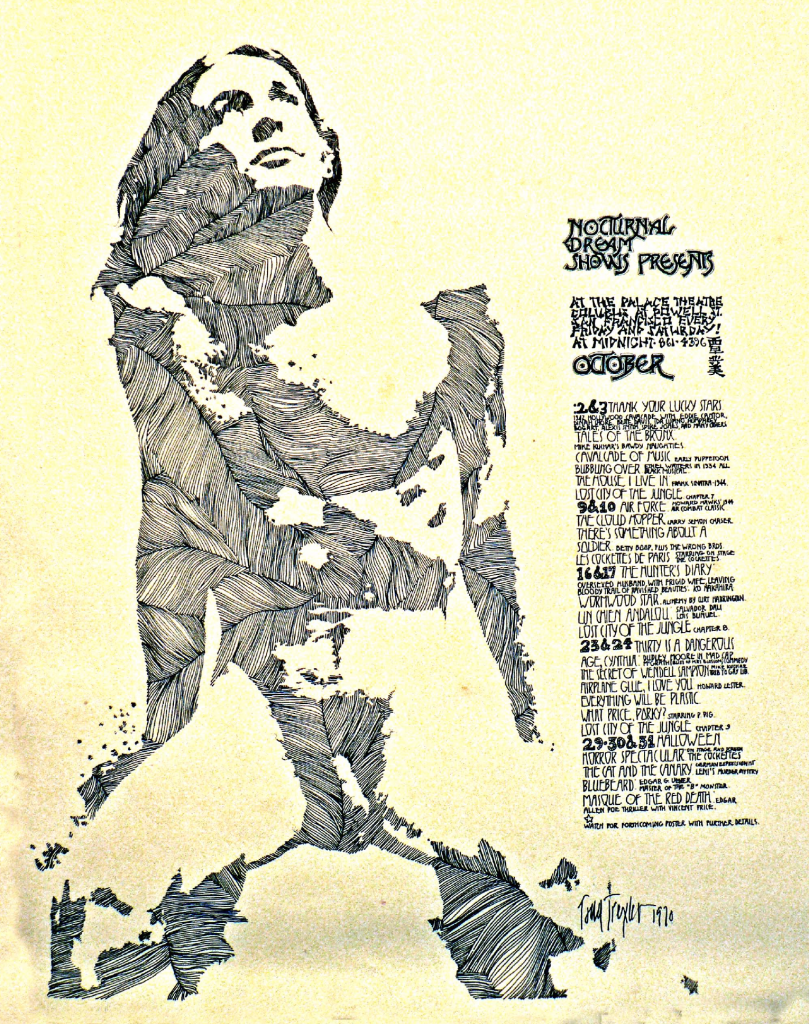

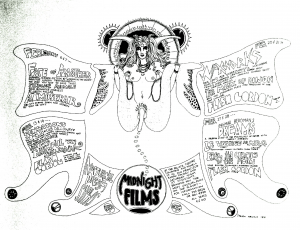

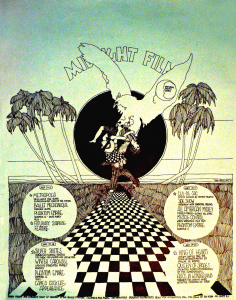

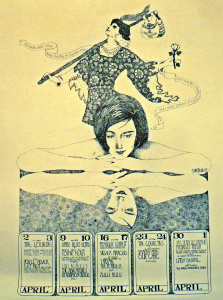

Even before there was Hibiscus, there was Milton Miron, known by the single name Sebastian, whose Nocturnal Dream Shows—his weekly midnight movie screenings—provided a birthplace for the Cockettes. The Dream Shows featured Noting my love for movies—with my passing on of verses inspired by the movies he presented—Sebastian invited me up one night to see the projection booth. At that time the evenings began with a chapter from the old Flash Gordon serial, and it suddenly struck me that the interior of Flash Gordon’s spaceship was itself modeled after a movie projection booth! The primitive special effects and costumes of such early serials were unabashed in their artificiality, and that was fer Until midnight, the Palace was a Chinese theatre which showed films, then staged live dramas. Our special treat was to watch the Chinese-Americans strike their scenery. The cardboard sets for those dramas would find their expression in the cardboard-thin artifice of the Cockettes’ early productions. During the set change, many Chinese-American men would run madly about the stage, striking sets made up of painted clouds, houses, and trees, the rudiments of art and illusion. The Cockettes emerged from this movie world when Hibiscus and his original group, the Angels of Light, surprised the audience one night before the movies began by walking down the aisle dressed like the Japanese women in a production The war in Vietnam had gone on forever, it seemed. Some who had spent a decade opposing the war, or involved in the complete The gay community owes a great deal to David Weissman and Bill Weber for their documentary about the Cockettes and its honest description of their rise and fall. Sadly, because none of the shows were ever filmed, the documentary cannot come close to revealing the great heart of the Cockettes that you could know only if you were present at one of their live shows (with titles like “Les Ghouls,” “Tinsel Tarts in a Hot Coma,” “Journey to the Center of Uranus,” “Hot Greeks,” and “Les Étoiles de Paris”). Satire and joy were wed in a way that defeated a world obsessed with war and machismo. They had, for a time, an innocence—like children throwing themselves with great abandon into fantasy dress-up—that healed a few war-weary souls. Jim Eilers’ poetry has appeared in this magazine as well as in Mouth of the Dragon, The San Francisco Express Times, and The San Francisco Reader. exceptional films for an exceptional klatch of film lovers. Each week, Sebastian composed a menu of short and long movies in the way a great chef harmonizes the dishes of a dinner, mixing classic moments in film with his own sound effects to suggest a new meaning. For example, for a silent short feature about Will Rogers performing his truly amazing rope tricks, Sebastian added a sound track of sitar music. At one point Rogers—still looking like the young Oklahoma Indian he was at the time, not the stand-up political comedian he became—danced back and forth in slow motion through the giant loops of his lariat, and, because of the sitar music, his rope tricks took on a mystical aura as if you were watching Shiva skip back and forth through the cycles of time.

exceptional films for an exceptional klatch of film lovers. Each week, Sebastian composed a menu of short and long movies in the way a great chef harmonizes the dishes of a dinner, mixing classic moments in film with his own sound effects to suggest a new meaning. For example, for a silent short feature about Will Rogers performing his truly amazing rope tricks, Sebastian added a sound track of sitar music. At one point Rogers—still looking like the young Oklahoma Indian he was at the time, not the stand-up political comedian he became—danced back and forth in slow motion through the giant loops of his lariat, and, because of the sitar music, his rope tricks took on a mystical aura as if you were watching Shiva skip back and forth through the cycles of time. tile ground for The Cockettes, whose weekly musicals harked back to the Busby Berkeley world of the 1930’s. (Sebastian would go on to make his own movie starring the Cockettes, 1971’s Tricia’s Wedding, which lampooned the White House marriage of Nixon’s daughter.)

tile ground for The Cockettes, whose weekly musicals harked back to the Busby Berkeley world of the 1930’s. (Sebastian would go on to make his own movie starring the Cockettes, 1971’s Tricia’s Wedding, which lampooned the White House marriage of Nixon’s daughter.) of Madame Butterfly. Carrying parasols and proceeding with mincing steps, they climbed onto the narrow stage in front of the screen in a brief sample of what was to come. At the time, most of the people in the audience were stoned on grass or psychedelic drugs and were already prepared to let movies become reality. The Nocturnal Dream Show that night was like a boisterous Old West saloon where rambunctious people were eager to be entertained. The obvious delight of the audience that night assured that the bearded geishas’ little song and dance on the stage would quickly mushroom into the zany productions of the Cockettes. (For those “on the inside,” there are arguments about how the Angels of Light became the group that became the Cockettes or how soon Hibiscus and his original troupe peeled away.) In retrospect, it seems the right moment for such a phenomenon: it was the 60’s, and everything was in turmoil, including sex and gender roles, which the Cockettes were determined to challenge.

of Madame Butterfly. Carrying parasols and proceeding with mincing steps, they climbed onto the narrow stage in front of the screen in a brief sample of what was to come. At the time, most of the people in the audience were stoned on grass or psychedelic drugs and were already prepared to let movies become reality. The Nocturnal Dream Show that night was like a boisterous Old West saloon where rambunctious people were eager to be entertained. The obvious delight of the audience that night assured that the bearded geishas’ little song and dance on the stage would quickly mushroom into the zany productions of the Cockettes. (For those “on the inside,” there are arguments about how the Angels of Light became the group that became the Cockettes or how soon Hibiscus and his original troupe peeled away.) In retrospect, it seems the right moment for such a phenomenon: it was the 60’s, and everything was in turmoil, including sex and gender roles, which the Cockettes were determined to challenge. transformation of U.S. society, were burned out, unable to continue the fight, and, with apologies to those who had the strength to struggle on, they had to drop out even while they felt overwhelmed with shame for dropping out as the killing went on. Many such psychological refugees from the 60’s were in the audience one night for the showing of a Japanese film, The Burmese Harp, which had special significance for the Cockettes. A Japanese soldier in the Burmese jungle tries to tell his comrades that World War II has ended, but they fight on in a stupid, unnecessary final encounter with the British. After the battle, the hero, out of respect for the dead, tries to bury those killed in the battle, but there are too many.

transformation of U.S. society, were burned out, unable to continue the fight, and, with apologies to those who had the strength to struggle on, they had to drop out even while they felt overwhelmed with shame for dropping out as the killing went on. Many such psychological refugees from the 60’s were in the audience one night for the showing of a Japanese film, The Burmese Harp, which had special significance for the Cockettes. A Japanese soldier in the Burmese jungle tries to tell his comrades that World War II has ended, but they fight on in a stupid, unnecessary final encounter with the British. After the battle, the hero, out of respect for the dead, tries to bury those killed in the battle, but there are too many.  For most in the audience, this was raw and real, as Vietnam was never far from their troubled consciousness. The soldier, isolated from his company, becomes so disillusioned that he goes through a series of changes and becomes a monk. When his fellow soldiers in their uniforms see him again, he’s dressed in long, flowing robes, a white parrot on his shoulder. It’s a very feminine look in sharp contrast to the soldiers—a look not unlike that of the Angels of Light or the Cockettes at certain times.

For most in the audience, this was raw and real, as Vietnam was never far from their troubled consciousness. The soldier, isolated from his company, becomes so disillusioned that he goes through a series of changes and becomes a monk. When his fellow soldiers in their uniforms see him again, he’s dressed in long, flowing robes, a white parrot on his shoulder. It’s a very feminine look in sharp contrast to the soldiers—a look not unlike that of the Angels of Light or the Cockettes at certain times.