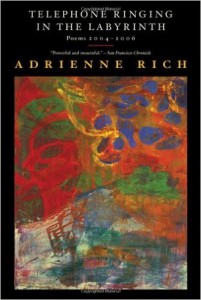

Telephone Ringing in the Labyrinth

Telephone Ringing in the Labyrinth

by Adrienne Rich

Norton. 108 pages, $23.95

“MORE AND MORE I dread futility,” confesses one of Adrienne Rich’s speakers in Telephone Ringing in the Labyrinth. “Maybe I couldn’t write fast enough. Maybe it was too soon,” Rich muses in another poem, as if her message might be better understood by future generations. Because she’s so well known for the groundbreaking poems that helped shape political movements in the second half of the last century, and has published a number of prose books (most recently, Poetry & Commitment and What Is Found There: Notebooks on Poetry and Politics) that probe the intersections of poetry and politics, it can be disturbing to witness Rich, honest as always, grappling with these uncertainties in her poems.

Perhaps her fear of futility results in part from being marginalized because of her leftist politics—and because of the wholesale marginalization of poetry by our culture. From the title poem of Telephone Ringing in the Labyrinth: A room papered with clippings: I worked to keep it current history as wallpaper Rich’s very belief in the task of keeping poetry “meaningful” seems to falter at times. She wonders finally “if such refractions matter.” This wavering in Rich’s sense of mission in her poetry contrasts with the greater sense of certainty that she exudes in her prose writings about the mission of poets and poetry. In Poetry & Commitment (2007), she endorses James Scully’s distinction between “protest poetry” (“‘conceptually shallow,’ ‘reactive,’ predictable in its means”) and “dissident poetry,” which “is a poetry that talks back, that would act as part of the world, not simply as a mirror of it.” As Rich seeks to practice it, dissident poetry maintains a commitment to uncertainty, being “an engaged poetics that endures the weight of the unknown, the untracked, the unrealized, along with its urgencies for and against.” Compared with the chiseled logic of her earliest work and the lucid, overtly political poems of her middle years (consider “Hunger” from The Dream of a Common Language or “For the Record,” written in 1983), the poems in her last three or four books are much more fractured, elliptical, and exploratory. Even her more experimental work of the 1970’s, influenced by Middle Eastern poetic forms and modernist cinematic techniques, resulted in more polished fragments. Why did Rich tilt toward less straightforward, accessible writing when so much of political import is going on around us, in this post-9/11 era of melting ice caps? Compare the recent poems by Rich’s contemporary Maxine Kumin, which do not mince words about the Bush administration’s use of torture in Iraq, with Rich’s rather tepid, tangential indictment of an academic response to tragedies like New Orleans’ (“The University Reopens as the Floods Recede”). Perhaps Rich had already written the equivalent of Kumin’s “torture poems” decades ago, and such directness now seems “merely formulaic” to her. However, if Rich worries about the futility of her current work (“searching for transformative meaning on the shoreline of what can now be thought or said”), I wonder if she appreciates that this later style may come between her and many of her readers. There’s an enormous difference between some of her poems from the 1970’s—which had such relevance to people’s lives that they came to be quoted in frosting on cakes at gay and lesbian weddings (!)—and the cut-up, elusive quality of poems like “Midnight, The Same Day” or “Skeleton Key.” And yet, the skeleton key that Rich’s speaker calls for should function like a common language, opening all doors, not leaving them closed by obscurity. At times, Rich’s former narrative clarity resurfaces and blends well with her nuanced perceptions. For instance, in the poem “In Plain Sight,” she describes scrutinizing people she sees in public to gather evidence of the pain that belies our efforts to hide it. Compared with some of Rich’s other recent poems, “Behind the Motel” possesses the old-fashioned æsthetic virtue of unity: its conventionally controlled structure fuels a heightened conclusion. “Hubble Photographs: After Sappho” explores the widest reaches of desire, contemplating our deepest loving relationships with each other within the context of our enthrallment with the immensity of the cosmos. Even if Rich has largely left off tightly orchestrating her poems and instead travels through them, this poem crosses vast distances while still allowing us to follow. Given Rich’s already enormous accomplishments, notably her ability to marry metaphor with revelation, the standard to which we hold her new poems is high. We’ve come to expect a poem’s labyrinth will become a passageway, and that the telephone message inside could change our lives. Steven Riel is the author of two chapbooks: How to Dream (1992) and The Spirit Can Crest (2003).

newsprint in bulging patches

none of them mentions our names

gone from that history then …

no matter:

and meaningful: a job of living I thought

urgently selected clipped and pasted

____________________________________________________________________