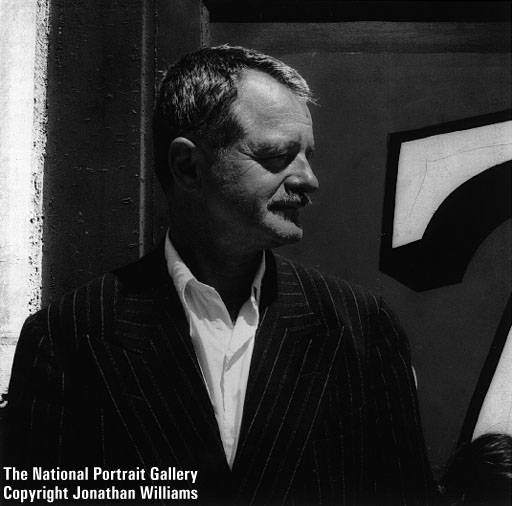

Jonathan Williams, who died on March 16 at age 79, was known for many things, but dullness was never one of them. Photographer, poet, essayist, folk art aficionado, and founder of the Jargon Society—an enterprise devoted to publishing “maverick poets, stray photographers, oligarchs, and characters,” and whose exquisite small-press productions now reside mainly in the hands of collectors—Williams possessed an ear for the poetry in ordinary speech, an eye for the ironic before that became fashionable, and a wit more conducive to the truck stop than the drawing room. He was something, .

Williams was born in North Carolina in 1929. He attended Princeton and later studied photography with Aaron Siskind and book design at the Institute of Design in Chicago before arriving at Black Mountain, where he founded Jargon.  Grants and donations sustained both him and his press. Williams and his life-long partner, the poet Thomas Meyer, who survives him, typically divided their year between Skywinding Farm, the property he owned in the Blue Ridge Mountains, outside Highlands, North Carolina, and a 17th-century stone cottage in Dentdale, Cumbria, England.

Grants and donations sustained both him and his press. Williams and his life-long partner, the poet Thomas Meyer, who survives him, typically divided their year between Skywinding Farm, the property he owned in the Blue Ridge Mountains, outside Highlands, North Carolina, and a 17th-century stone cottage in Dentdale, Cumbria, England.

At the center of all his many accomplishments was his poetry, and it is as a poet that he’ll best be remembered. At Black Mountain College in the 1950’s, Charles Olson advised his writing students, JW among them, to “be romantic, be passionate, be imaginative, and never be rushed.” This was startling, and it took. No one, Williams remembered, “had ever told me things like that at docile Princeton.”

JW’s subsequent lyrics—dry, terse, bawdy, erudite—caught the tone and sensibility of their irascible author rather perfectly. But his great contribution to postmodern verse and its currents—Beats, Black Mountain, San Francisco Renaissance, New York School—is the found poem, that ready-made verbal object only waiting to be transposed into print. Of this genre he was the master. He loved to reveal the poetic within the pedestrian, whether from commercial signs (one read “O’Nan’s Auto Service”), amorous lavatory wall scribblings (“The Current Sexist Machismo in a Loo Along the River Kent”), buffoonish headlines (“Nancy:/ Together/ We Can Lick/ Crack”). Sharp eyes and ears were the required equipment.

In “Blues & Roots/ Rue & Bluets” (the title, half at least, borrowed from a Charles Mingus album), he took this a step further, reworking into open verse the sometimes ornery observations of the Deep South mountain people he’d interviewed in the course of his folk art research, to juicy effect. This from “The Colossal Maw from War-Woman Dell, Georgia,” for instance: “more mouth on/ that woman/ than ass/ on a goose.” In these poems he functioned much like the obscure, marginal composers he so admired, who often drew on folk tunes for their melodies.

Like all great minds, JW’s churned with restlessness. He infused light verse forms such as limericks, clerihews, and acrostics with his own ribald wit, and he invented a form of his own called the Meta-Four. This specified no length, only that every line contain four words. Some meta-fours consisted of a single line (“Nude Driver Threw Lard”). Some ran a page or longer. Typically they offered the poet’s wry take on things banal:

the french enjoy westerns

with subtitles i like

the one where the

cowboy pushes through the

swinging doors hoists himself

onto a bar stool

the bartender turns around

and says howdy and

the cowboy says enchanté

Williams’ gay poems combined his usual celebratory and linguistic apparatus with the author’s horny worldview, typically in the service of humor. I’m thinking of gAy BCs, a chapbook, circa 1976, containing one Williams poem and drawings by Joe Brainerd, said poem consisting of an alphabet of names, along with salient sexual characteristics (“Eds are said to give head”).

The pleasure of his company, in person or in print, owed to the breadth and unconventional nature of his interests, from white trash cooking to the music of Frederick Delius. His books of collected quotes, his excellent photographs, and his several volumes of essays—The Magpie’s Bagpipe (1982) and Blackbird Dust (2000)—convey all this as much as the poems do. Whether it was a riff on John Cage, an interview with Basil Bunting on the occasion of the latter’s 80th birthday, or a report on “A Walk in Wales,” whatever he wrote sought to amuse, engage, and amplify.

He made a point of heralding the odd and the obscure, and seems it almost beside the point to lament a writer far more interested in jubilation than sorrow. He leaves behind a long trail of publications, all of it small press but easily tracked down. What Jonathan Williams once wrote about the late James Laughlin applies equally to himself: “A man who has done as much great work … deserves our respect, our love, and our indulgence.”

Jim Cory is a poet and lives in Philadelphia.