FROM his first trip down the Nile at age six, when he sat on the knee of the famous Aga Khan, Hanns Ebensten was captured by a wanderlust that carried him through his long life. His love of adventure and intrepid spirit led him to remote islands, desert oases, mountaintop villages, and faraway lands that most people could barely imagine.  Nineteenth-century diaries, maps, and his beloved 1929 Baedeker travel guides fueled his passion for travel and his insatiable appetite for exploring the world. Hanns’ life was filled with caravans and train rides, charter planes and jungle safaris, but it was also one of outrageous gay philandering and a penchant for tattooed men in torn jeans and uniforms. Hanns escorted royalty and tearoom queens, played bridge on the Orient Express and hanky-panky with guards in a Borneo zoo. But in the end, Hanns was both a perfect gentleman and the quintessential world explorer.

Nineteenth-century diaries, maps, and his beloved 1929 Baedeker travel guides fueled his passion for travel and his insatiable appetite for exploring the world. Hanns’ life was filled with caravans and train rides, charter planes and jungle safaris, but it was also one of outrageous gay philandering and a penchant for tattooed men in torn jeans and uniforms. Hanns escorted royalty and tearoom queens, played bridge on the Orient Express and hanky-panky with guards in a Borneo zoo. But in the end, Hanns was both a perfect gentleman and the quintessential world explorer.

Even in his later years, having decried the “tourist” industry—tourism as distinct from travel—Hanns sought places where few people would venture. One of his last great treks was leading a group of men to the remote oasis of Siwa in Egypt’s Western Desert. “I went to Siwa on my own in January 2005, and although I am a devoted admirer of Easter Island, the monasteries of Mount Athos, and the Inca and pre-Inca remains in Peru, Siwa appealed to me, even far more than those magical places. It was the most moving and stimulating travel experience of my life.” (And it was the last tour that he led in his 50-year career of leading memorable tours.)

Reaching the beautiful, fertile oasis of Siwa requires a two-day drive across the desert. The main town, Shali, used to be fortified, and the oasis tribe of warriors, the zaggala (“club bearer” in the Siwa language), defended it against desert raiders. For many centuries, it has been the custom that these stalwart men may not reside in town and may not marry until the age of forty, and they live a carefree bachelor life in the palm groves, cultivating the dates and olives. Early 20th-century scholars reported that homosexuality was totally normal and natural for them, and that their weddings to young men were celebrated with lavish feasts, much drinking of loubki (the highly intoxicating liquor made from the hearts of palm trees), and boisterous dances and songs. Since the 1940’s, the prudish Egyptian authorities have forbidden these uninhibited ceremonies (which are reputed to continue in secret), but the oasis is still an all-male enclave. All the staff in the hotels, cafés, shops and offices are men, most of them wearing the traditional robes, and all are extremely courteous and polite to strangers.

Hanns’ love for travel and all-male company led him to create the first organized trip for gay men in 1972, earning him the moniker of “inventor of gay travel.” In 2004, the iglta (International Gay & Lesbian Travel Association) named him “Pioneer of Gay Travel” and honored him by calling their annual citation the Hanns Ebensten iglta Hall of Fame Award. The idea for the all-male tour occurred to him while rafting down the Colorado River in the Grand Canyon. He was tired of “dreary men and women with their screaming babies and kids who kept asking for dinner.” It occurred to him how wonderful it would be to crash through the rapids surrounded by the beauty of the canyon with “like-minded men … in their boots, Levis and cowboy hats in the environment for which they had been designed, instead of being worn in the bars.”

Thus began Hanns Ebensten Travel, still a thriving company that continues to honor its founder’s principles of travel. (Full disclosure: I do marketing for Alyson Adventures and for Hanns Ebensten.) But Hanns’ legacy goes beyond the creation of his travel company. He authored eight books, beginning with Pierced Hearts and True Love: An illustrated history of the art and development of European tattooing in 1953, and finishing with Egypt in My Blood, published just weeks before he died. The books are filled with his highly opinionated insights and hilarious tales of his travels and co-travelers. He describes a time in Turkey when a guy named Fatso’s admiration for the fawning young Turkish boys cost him an expensive watch, and a night in a Florence hostel when 98 motorcycle cops were billeted in the dormitory-style facility, leading to a night of debauchery: “The arrival of these Cocteau-like angels of death turned the dormitory into a homosexual’s dream come true. Helmeted like ancient gods, these sturdy gorgeous men began to fill the hall. … Even before lights out at 11 PM there was no mistaking the aura of sexuality … they loitered in dimly lit washrooms, corridors and on the circular stairs between floors, smirking sensuously, groping their genitalia under their uniform pants and hissing invitingly, ‘Cazzo grande, cazzo duro.’”

Despite Hanns’ insistence that his charges dress modestly and behave with decorum—even insisting they bring dinner jackets to the desert for tea—there was no denying that both he and his groups often enjoyed the men they met during their travels. But Hanns’ fondness for things homosexual (he despised the term “gay”) also led him to historically significant discoveries. In his seventh book, The Quest for Dibbish, he describes his long search for the story of a lovely young servant whose portrait he had seen in an important Cairo house belonging to Egypt’s reclusive last British pasha. Hanns’ curiosity led him to believe that Dibbish was the pasha’s lover, but he discovered there was not one but many “Dibbishes” in the house. It seems the pasha, Sir Gayer-Anderson, employed a series of young men who attended to his needs over the years.

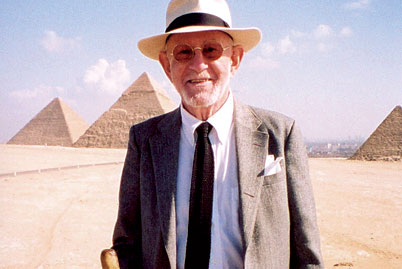

For all his wanderlust and dalliances, Hanns found peace and quiet in his small home on a shady lane in Key West, sustained by his 41-year committed friendship with his partner, the late Brian Kenny. He never owned or drove a car and walked everywhere around Key West wearing his formal white suit and black tie and his ubiquitous boater hat. Hanns celebrated his 82nd birthday on the Nile in November 2005, and passed away in July 2006, still planning his next visit to his Bedouin friends in the Sinai Desert.

Daniel Di Stasio is a travel and fiction writer whose work has appeared in Out Traveler and other publications.