THERE HAVE BEEN at least two major studies of the family that produced the novelist Henry James. One, by F. O. Matthiessen (the revered Harvard scholar), was published in 1941; the other, by R. W. B. Lewis (biographer of Edith Wharton), came out in 1991. But Paul Fisher says in the introduction to House of Wits just what you would expect of someone writing yet another version: that “a more complete and modern portrait of this family has not been possible until recently,” because before “the last decade or two, few people talked or wrote about the most intimate issues in the Jameses’ lives.” That must be why House of Wits might as well be called “House of Homosexuality, Nervous Breakdowns, Back Pain, Alcoholism, Insecurity, Social Climbing, Sibling Rivalry, and Constipation.” This, in short, is a book about the James family as neurotics.

Hermione Lee (another biographer of Edith Wharton) wrote in her New York Times review of House of Wits that Fisher seems to really have nothing new except an emphasis on Henry James Senior’s drinking problem and the claim that, even though the paterfamilias got sober after discovering the solution to his restless search for meaning (the Swedish philosopher Swedenborg), the James brood were still the children of an alcoholic. But that’s not all: Henry Senior also lost half his leg after putting out a fire as an adolescent in Albany, New York, where his father, an Irish immigrant, had made himself the richest man in town (though his grandson the novelist would boast that not for two generations had his family been guilty of trade), and he cut Henry Senior out of his will because his impetuous son had squandered his youth drinking and knocking around from place to place.

Eventually, Henry Senior did discover a calling (as a journalist–philosopher). He also married—a woman from New York brought up in precisely the same environment as the heroine of Washington Square—and then became obsessed with making his children successful, uprooting them repeatedly in his effort to give them a “sensuous education.” Ultimately, with a cold-blooded allocation of resources that may shock the modern reader, it was decided that only the two oldest children were worth banking on—Henry (or “Harry”) and William. The other two sons were thought suitable at best for business, while daughter Alice was simply to be a Victorian woman, i.e., a “ministering angel” to the men. This means Henry and William were enrolled at Harvard while Bob and Wilkie were sent off to fight in the Civil War. In other words, in Fisher’s book, Henry Senior comes off a bit like Mama Rose in Gypsy.

Gypsies they were for many years—hotel children yanked from one school after another in Switzerland, France, Germany, England, and New England. One of Fisher’s pleasures is a detailed description of every transatlantic steamer any James took in their recurrent flitting back and forth between Europe and the U.S.A. (House of Wits has two strands: the neurotic history of the family, and detailed descriptions of the world in which they lived.) Fisher tells us just what it was like to vacate the James house on 14th Street in the summer of 1855 and ferry across the Hudson to the Jersey shore to embark on the SS Atlantic—the carriages, the luggage, the staterooms, the history of marine disasters. This book is a bit like Ragtime, describing the look and feel of a rapidly expanding, industrializing America. Fisher means to bring things alive: “In the July heat of 1870, the great ballroom of the Grand Union Hotel in Saratoga Springs felt especially stifling”; “reclining in a gondola while a boater-hatted gondolier poled him around, Harry toyed with other fascinations.” No noun is sent out without an adjective—though it can get a little silly: “the yellow sunshine” of a New England autumn, “the manatee-haunted St Johns River.” Still, the pleasure of reading Fisher’s book—a guilty one—is just this effort to bring the scene to life. But what makes it possible to read this familiar story yet again is Fisher’s viewpoint, which is essentially to regard the James family as an incestuous house of competitive and highly verbal Victorians entering the modern age under stress.

“They were always outsiders” is what the movie tagline might be. Even the places they lived were on the margins of the fashionable. They weren’t rich enough for the real thing—and they were hard to place. Henry Senior didn’t have a job, or a very fixed address, and he liked to say outrageous things in polite company, such as praising free love (though he was rigidly Victorian with his own family). But the Jameses were good friends of the Ralph Waldo Emersons, and when they went to Europe they always had letters of introduction to people like Thackeray and Thomas Carlyle; and when Henry Junior finally got to England on his own, he wasted no time gaining admission to the clubs and country houses of the aristocracy. Nevertheless, Fisher refers often to the “insecurities” of both Henry James Senior and Junior. Senior, after all, was an oddball who gave speeches his audience couldn’t understand and wrote philosophical books that few people bought, and was able to take his family to Europe (and grant his children individual trips when they got older, though always under a pretext of improving one’s education or health) only because he’d inherited one-eleventh of his father’s Albany estate. Near the end of the book, in fact, Fisher simply calls Henry Senior not only “moralistic” but “mentally ill.”

Is it thus a surprise that not all the children turned out well? The two youngest sons were business failures after the Civil War: Wilkie died bankrupt before he was 39; Bob died an alcoholic separated from his wife; and Alice, the heroine of Fisher’s book, is only one of several martyrs to the Victorian role of women (her mother, aunt, and sister-in-law were others). Of course, when one asks oneself, “Why am I reading about these people?” the answer, I think, is clearly: Henry. And why do we want to read about Henry? The official reason is his achievement as a writer; but at this point we are way beyond that. At this point, we are cannibalizing Henry for many reasons. James said that all any writer can do is “cast one’s little spell—the rest is the madness of art.” But the modern age is more literal. Literate Americans find many things about James fascinating: his brilliance, his social life, his preference for Europe, his disaster in the theatre—and, more and more, the suspicion that he was a closeted homosexual.

House of Wits revives such matters as James’ intense dislike of Oscar Wilde, his searching his friend Constance Fenimore Woolson’s papers after her suicide, his refusal to admit to his brother that he knew John Addington Symonds—his determination, in other words, to avoid any association with the love that dared not speak its name. In Fisher, one is struck again by the fact that Henry came out of a very New England childhood, had Victorian ideals of “manliness,” and was never able to leave his adored mother’s notions of respectability behind. His Irish roots and his homosexual orientation were two things he did not want to be associated with—which leads Fisher to call him “a prisoner of fear.”

That’s Fisher’s interpretation, at least. But how does one interpret the interpretation? Fisher makes James’ sexuality much more prominent than did Leon Edel, the grand-daddy of James biographers, for instance. Consider Paul Zhukovsky, the Russian émigré James met in Paris the year he lived there and made friends with Turgenev. Years later, after James had moved to London, he was invited to a reunion in Italy with Zhukovsky when the latter was living near the villa that Richard Wagner had taken south of Naples. James went, but found Zhukovsky’s circle so repulsive that he cut his visit short and left. In Edel, James fled, took a room in a nearby town, and, gazing out over the Bay of Naples, felt “himself again in tune with the world.” In Fisher (whose version of the episode is both longer and pitched higher), James gazed out over the Bay of Naples in the direction of Posillipo, “as if Harry was straining to see back into the world he had lost.”

Both biographers quote from a letter James wrote to his old friend Grace Norton (the sister of a Harvard fine arts professor who seems to be, the more one reads these biographies, James’ real touchstone). Yet the two portray James’ inner feelings at that moment in opposite ways. It’s a small thing, I suppose—what James was feeling as he gazed out over the bay—but it shows you how subjective biography is. Both Edel and Fisher admit we cannot know exactly what James recoiled at when he visited Zhukovsky (a “ridiculous mixture of Nihilism and bric-a-brac,” said James). But Fisher spends much more time with it than Edel and uses a statue of “the mutilated Psyche” in the Naples museum that James sees after Posillipo to add, in what amounts to a distillation of his entire thesis: “Harry’s own psyche was ‘mutilated’ enough, as were those of the other Jameses, all of whom seemed bent on running away from the people they most loved. The ‘mutilated Psyche,’ in fact, might have described the emotionally crippling Victorian era itself.” He then discusses Freud and Eve Kosovksy Sedgwick (The Epistemology of the Closet), and goes on to juxtapose James’ fleeing Zhukovsky with his making friends afterwards in Florence with Constance Fenimore Woolson (the lonely, deaf writer whom Edel nominated to be James’ unconsummated love).

Following Posillipo, furthermore, James spent a day with friends near Rome whose “admirable, honest, reasonable, wholesome English nature” he much preferred to the “fantastic immorality and æsthetics of the circle I had left in Naples.” So what did James find in Posillipo? One imagines a nest of screaming queens passing Wilhelm von Gloeden photographs around. But how can we know James’ own feelings? In a note, Fisher cites the various reasons that previous biographers—Leon Edel and Sheldon Novick—have given for James’ fleeing Zhukovsky: “Edel emphasizes discomfort … Novick underlines Harry’s objections to nihilism.” That’s the problem in a nutshell; each biographer tinctures it a bit differently. But the growth of the importance of James’ rejection of Zhukovsky—from Edel to Novick to Fisher—is one index of the way in which homosexuality has come to be seen as key to James’ personality.

“In the palace, all was speculation,” Ronald Firbank wrote: an epigraph that might stand, to various degrees, for all biography. As Hermione Lee pointed out, Fisher relies on a lot of phrases a biographer falls back on when conjecturing—no doubt, must have, might have, etc. The giveaway moment in this book comes toward the end, I think, when Fisher describes the last Christmas James spent in Lamb House, during which his one houseguest was a depressed journalist having trouble with his marriage, and, for Christmas dinner, his guests consisted of his typist Miss Bosanquet and her “lady-pal.” In Fisher’s scene the women find James’ annual Christmas gift of gloves amusingly old-fashioned (the old Victorian!), but not as amusing as the mask James dons in observance of an English Christmas custom—a mask that turns Henry into “a fat old lady with side curls.” Well, well! This takes the lonely homosexual spinsterhood that novelist Colm Tóibín portrayed in The Master (2004) and ratchets it up to Richard Burton and Rex Harrison in the movie Staircase. So this, I thought when I read the startling passage, is where it’s all been heading—James in drag is what our generation wants!

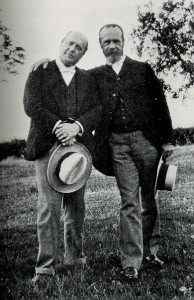

In other words, now that the subject of homosexuality is out, it’s open season on James’ celibacy. In Tóibín’s novel, James is a lonely bachelor who must contend with a valet trying to seduce him on a visit to a fashionable woman who’s trying to uncover his secret. In Edmund White’s novel about Stephen Crane and James, Hotel de Dream (2007), James is a fat queen whom Crane’s mistress finds silly, but who brutally destroys Crane’s manuscript because it might cause a scandal. And in Joyce Carol Oates’new book, Wild Nights (short stories about famous writers’ final days), while visiting a veterans’ hospital in London, James buries his face in the lap of a wheelchair-bound soldier with whom he has fallen in love, and is beaten afterwards with a cane by the head nurse for losing control. What’s this? Revisionism and revenge! And what a tempting target, to be honest: this pompous bald man in a straining vest who looks like a banker with heartburn in Sargent’s late portrait.

Clearly, James has fallen on the wrong side of our feelings about the closet: Oscar Wilde is the hero when it comes to modern homosexuality, while James was repelled by Wilde (“a fatuous cad,” “a vile beast”). James is the stuffy New Englander obsessed with the very respectability that Wilde rebelled against. And when you think about it, what are James’ themes? Fisher sums them up this way: “the Europe of loaded heiresses, exquisite art, and imperiled innocence.” So many of his plots are the stuff of women’s fiction; even The Golden Bowl might be summed up as: “Can this marriage be saved?” But the stories we love now are about loneliness, self-denial, the price one pays for not having loved, or lived: The Beast in the Jungle, The Altar of the Dead, The Ambassadors, The Wings of the Dove. James has become for this generation a martyr to sexual repression (it was his own deepest loneliness, he admitted, that he wrote out of), not unlike the poet Gerard Manley Hopkins.

Of course, compared to Hopkins, James was a social gadabout. On hearing that William Dean Howells had told someone at a party in Paris that he felt he hadn’t “lived,” James turned this into The Ambassadors. He was also an indefatigable worker, an extremely ambitious man whose success led Edel to title one of his volumes “The Conquest of London.” But now we have the Freudian backlash: an age that considers sexual repression contra-indicated mocking an age when it was a condition of existence. Fisher views the James family through the lens of gender, feminism, and the “epistemology of the closet.” He even points out that Henry stole from Alice—the way, a recent biography argued, F. Scott Fitzgerald stole from Zelda. Every age has a prism through which it views past lives—a set of values that no doubt will be viewed years later as having given us as strange and narrow a perspective as the one we mock the Victorians for. Ideas, after all, are in a sense only organizing principles that try to neaten the clutter of existence and distort reality to do so.

So how stuffy was James? How prudish, how tortured, how closeted? Even the anecdote about the visit to Wilde when both men happened to be in Washington can be interpreted variously. When James called on Wilde and asked if he missed London, Wilde replied, “Oh, you care for places? I am a citizen of the world.” But why did this infuriate James? Was it a putdown of his attempt to be friends? Or did it just confirm James’ visceral dislike of a flamboyant æsthete who was both Irish and homosexual? James is lately drawing a lot of attention from biographers and novelists alike. When I first heard about Colm Tóibín’s novel, I thought: why on earth would anyone fictionalize James’ life when there’s already a five-volume biography; why speculate when someone has gone to such pains to ascertain the facts? The answer, I guess, is to give us the feelings, the subjective reality, that facts cannot. But Tóibín only took further what so many biographies have been doing lately. Using novelistic techniques to set the scene, Fisher wants to help us feel what it was like for the young James to watch the muscular arms of the gondoliers on his first visit to Venice. The desire to put the reader in the moment is evident in Sheldon Novick’s recent biography (more novelistic than Edel, less hopped up than Fisher), too. In fiction, The Master, Hotel de Dream, and Wild Nights go all the way.

So what’s your pleasure: a dignified biography, a novelistic biography, a historical novel, or a novel? Fisher says in his acknowledgments that he spent a day talking about the James family with Tóibín, whose book makes much of a night James spent with Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. in the White Mountains of New Hampshire, and while that scene is not in House of Wits, Fisher uses another for the same purpose: the day Henry saw Gus Barker (a handsome cousin, who bled to death years later after a battle in the Civil War) posing nude for his brother William’s life class in Newport.

In the end, the reader must view the data and draw his or her own conclusions, since the mound of books about Henry James is unlikely to stop growing. Reading about other people—whether in a five-volume biography or a New Yorker profile—is to be presented with a mass of data, scenes, anecdotes, dates, and facts; and then, out of this mass of information, to seize on one or two things (which may be quite small) to form our opinion of the person. Which Henry do you believe? (And what did he sound like? I keep thinking that if I knew how English or American his accent was, I could answer all these questions.) Every biographer, depending on when his life was written, has access to different materials, so that in a case like Henry James (or Lincoln, or Proust, or F. Scott Fitzgerald), each version is like a city built on the one beneath it. Besides that, biographies, of course, reflect the age in which they’re written (and Fisher seems to have it in for the Victorians as much as Lytton Strachey), and each biographer is free to mention and/or dramatize what he wants to. But how far the portrait of Henry James has come!

Henry Adams (who wrote his own autobiography, in the third person) advised James that writing one’s own life was the only way to keep other people from doing it. James’ response was to write two volumes of memoir before he died, and burn his papers on the lawn of Lamb House (though he left his notebooks and 10,000 letters behind); all of which brings us to F. Scott Fitzgerald, whose dictum we should recall when reading any of these books: biography is the falsest of the arts. How, indeed, does anyone have the chutzpah to write a biography, to portray, evaluate, another person? Is there any such thing as the proper distance, the perfect tone? The book about the James family by F. O. Matthiessen, the man who founded American Studies at Harvard, is far better written than Fisher’s, and has a dignity wholly absent from House of Wits, which Hermione Lee aptly said infantilizes the whole James family (which is what Freudian thought, in a sense, does to all of us). But Matthiessen, a closeted gay man who later committed suicide, was writing in 1941, when American culture was so very different. (Nothing gives a greater sense of how much the culture has changed than comparing Mathiessen’s introduction, in which he says his book is about not just a family but “a family of minds,” to Fisher’s preamble. It’s the distance we’ve traveled from Queen Victoria to Freud to Oprah, Doctor Phil, People magazine, and Jerry Springer.)

Matthiessen lets the family members speak for themselves: his book is spliced with a generous selection of their writings. Fisher supposes, imagines, speculates, and dramatizes. House of Wits, one suspects, would no doubt have horrified James. It’s the result of what James called “the catastrophe of publicity.”

And yet: as a writer, I can’t imagine writing a biography. As a reader, however, I’m very glad so many writers do; and that includes Fisher. And yet, for all his book’s less than chiseled writing, the license it takes to imagine subjective states, it carries the reader through a remarkable family saga with a jargon-free readability that, I suspect, contributes its own portion of the truth.

Andrew Holleran’s latest book, reviewed in this issue, is Chronicle of a Plague, Revisited.