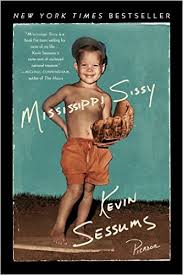

Mississippi Sissy

Mississippi Sissy

by Kevin Sessums

St. Martin’s Press

305 pages, $24.95

THERE IS a growing literature attesting to the terrors and gothic comedies of growing up gay in the American South. With his memoir Kevin Sessums has produced a masterpiece that outshines all other contributions to this genre since Truman Capote’s Other Voices, Other Rooms, and it will surely endure as one of the pre-eminent accounts. Sessums catches the obsession with athletics and hunting, the horror of any femininity in boys, the vicious small-town gossip, the demand for rigid conformity, the squashing of sensitivity and feeling, the disdain for artistic and literary endeavors. He outdoes Sinclair Lewis’ derision in Main Street, combining camp observations with a keen awareness of the troubles of racism, much like Lewis’ Kingsblood Royal. Above all, he masterfully portrays the ignorance, the drabness, and the dreadfully bad taste of small-town Mississippians. He shows why gays and other sensitive people cannot tolerate the South.

Sessums was born in Forest, Mississippi, during the height of the McCarthy era’s paranoia about commies and queers. It was a dangerous time anywhere in the country for a sissy to transit from childhood to puberty. Sessums upped the ante: he was not merely a sissy, but a demanding sissy. At age four he already wanted to wear dresses. His mother, a sensitive and spirited woman, indulged him, much to the outrage of his father, a stymied professional sports star and high school coach (yikes!).

Kevin had fits of temper that relatives could quell only by addressing him as “Arlene,” knowing that this invocation of his heroine Arlene Francis would calm him. No one can write a book about the South without touching on racism, and Sessums deals with it deftly and tenderly in his portrayal of the family’s illiterate but intelligent black maid, Matty May. The household provided Kevin with refuges, but as he continued to defy gender norms, an explosive confrontation with his father seemed inevitable.

But then his father died in a freak auto accident. Soon thereafter his mother contracted terminal cancer. On her deathbed she encouraged him to stand up to the hostile world, and the supervising grandparents allowed Kevin to go to his school’s Halloween party dressed as a witch. All hell broke loose, the adults perceiving the costume as drag.

Kevin escaped to Millsaps College in Jackson, the most elite private school in the state. There he met Frank Haines, an outstanding literary critic whose work appeared as far afield as The New York Times. Haines introduced him to Eudora Welty’s circle, which Sessums describes with insight and wit. As in so many small Southern cities, the artistic gay elite banded together to chat about movies, plays, books, and goings-on. Welty and her allies struggled to improve cultural life in Jackson, the only poor excuse for a metropolis that Mississippi has to offer even now. Sessums’ account of the uphill effort has comic touches, evoking the predicament of creative souls in so stagnant a time and place. He makes it clear that Welty and her inseparable longtime companion were lesbians, and does it so affectionately that she couldn’t possibly have objected.

Sessums’ discovery of the bound and mutilated body of his older patron, Haines, with whom Sessums never had sex but whose home was the springboard for his long-planned escape to New York City, brings the story to a horrific climax. There has been commentary about the crime’s resemblance to the skullduggery in John Berendt’s Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil. The comparison is in some ways inapt, but Sessums, like Berendt, does have a dead-on ear for magnolia perversity. He has written a landmark memoir that could be made into a hilarious movie. There must be a child actor somewhere who could portray four-year-old Kevin as he appears in a photograph on the book’s cover, precious and swishy, feyly holding an outsized baseball glove.

Reading Sessums, one is reminded to what extent the South has truly become what H. L. Mencken called a “desert of the beaux arts.” Southern culture as we once knew it is no longer distinct or important. The leading voices of the Southern Renaissance, the Southern Review and the Sewanee Review—at opposite ends of Mississippi’s borders—and the Kenyon Review, are not what they once were.

The Southern Literary Renaissance began with one of the reviewers’ cousins, William Alexander Percy, a sort of godfather to the Fugitives and the Agrarians. It reached its apex with William Faulkner and Tennessee Williams, with Margaret Mitchell’s Gone with the Wind standing as a solitary monument all its own. Because of these various talents, Mencken’s derogatory phrase really didn’t apply when he uttered it. But the Renaissance ended with the death of Flannery O’Connor and three Mississippians: Walker Percy, Shelby Foote, and Eudora Welty. The old aristocratic, often Catholic elite has disintegrated or fled north. Greenville, the long-thriving river port in the heart of the Delta, has collapsed economically and as a cultural center, having long ago produced its last great writers. Biloxi has its casinos, revived after Katrina, but its gem, Beauvoir, is still unrestored. The cultural bastion to which many are fleeing is Oxford, Faulkner’s home and the locus of Ole Miss.

There is of course a thriving African-American culture, but it did not enter Sessums’ all-white world at Millsaps, and unfortunately it still fails to interact with the remnants of the once-flowering school of Mississippi white authors. The most literate blacks had fled to New York by the 1920’s and 30’s to join the Harlem Renaissance. African-American culture is so hostile to the Confederate monuments and the flag (which became in the 60’s implacable symbols of racism and slavery) that not even reconciliation, let alone a higher synthesis between the two cultures, seems possible.

As intellectuals and even artists become increasingly connected to colleges, it is worth noting that most of them at Millsaps and Ole Miss are either not Southerners or were educated outside the South. Like John Howard’s Carrying On (1997) and James Sears’ works on the South, Sessums shows why white, gay intellectuals are stifled in the South, and by implication why Southern blacks, in many cases bound to homophobic Protestant fundamentalism, haven’t created a high culture. The South still lacks a safe place for black and gay intellectuals.

Note: Another new book, Gary Richards’ Lovers and Beloved: Sexual Otherness in Southern Fiction, 1936–1961 (LSU Press), arrived too late to be considered for this review. —WAP

William A. Percy III is the cousin of William Alexander Percy and also a cousin of Walker Percy. Aidan Flax-Clark is a recent graduate of UMass-Boston who double-majored in Greek and Russian.