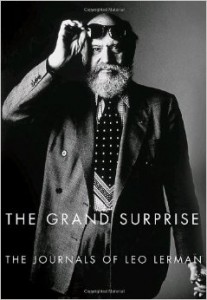

The Grand Surprise: The Journals of Leo Lerman

The Grand Surprise: The Journals of Leo Lerman

Edited by Stephen Pascal

Alfred A. Knopf. 654 pages, $37.50

ALTHOUGH HE DIED IN 1994, Leo Lerman is still, thanks to the diligent efforts of editor Stephen Pascal, sharing his stories and comments about everyone who was anyone in New York for half a century—and still making us all envious of the frenetic, joyful, art-filled life he led. The title refers to a prized species of butterfly, the Camberwell Beauty, known among collectors as “the grand surprise,” which Lerman had loved since first seeing one quite by chance as a ten-year-old growing up in East Harlem and Queens. He was collecting insects and butterflies that summer, attracted to their beauty and glamour. Writing about this childhood episode while in his early forties, Lerman enhanced the memory as he described how the butterfly raised its wings “languorously,” in much the same way that he would later see Margo Fonteyn raise her arms. His description of its purple wings as the color of “marvelous ancient Chinese silk” captures the sensations of a ten-year-old but reflects Lerman’s experience as an adult gay man who was at home in the fashion publishing industry.

An arts and entertainment writer and editor for almost fifty years, Lerman immersed himself in New York’s cultural scene like no other critic of his day. He became a contributing editor at Mademoiselle in 1949 after reviewing for The New York Herald and Atlantic Monthly, among other magazines, starting in the early 1940’s. In the 50’s he contributed to Playbill, Dance Magazine, and The New York Times. Following a brief stint as editor of Vanity Fair in the mid-1980’s, he continued as features editor at Vogue and finished his career, and his life, as editorial adviser to all Condé Nast magazines.

A blur of energy, Lerman threw weekly parties and occasional soirées on a grand scale, at which congregated the crème of the New York literary, artistic, and even political crème. Pascal includes several of Lerman’s more dazzling invitation lists, which demonstrate the extraordinarily eclectic nature of Lerman’s social connections and the reach of his tableau. The nearly 200 invitees to a “Welcome the New Year” party in January 1976 included the likes of Leonard Bernstein, Estée Lauder, Anita Loos, Gwen Verdon, Celeste Holm, Arthur Laurents, James Ivory, Richard Avedon, Lee Radziwill, and the late Luciano Pavarotti.

Stephen Pascal’s hefty collection of Lerman’s journal entries weighs in at well over 600 pages but represents only about ten percent of Lerman’s writings, the bulk of which were discovered after his death. Although Lerman had been under contract with a publisher to write an autobiography, he never ended up producing one. His longtime partner Gray Foy found the notebooks in a variety of hiding places. The entries cover a time period from just before his first assignment for Vogue in 1941 to a year before his death.

There’s a touching, reluctant, but honest acknowledgment on Lerman’s part that creeps in every so often: the realization that he was never going to write the Great Work and be the writer-as-artist that he wanted to be. For all the reams of art reviews and critiques and occasional pieces that he wrote for so many magazines, he was never able to translate his mastery of the written word into a sustained piece of fiction or scholarship. And while some might dismiss his journal entries as snippets of bitchy commentary, they are in fact keenly insightful impressions of the many illustrious people he met and events he attended in his glorious hometown of New York. Lerman described his own style of commentary in the following way: “I do not have the kind of ‘content’ expected. I am not intellectual; I am emotional, intuitive. I do atmospheres and surfaces and lightness with sincere deep feeling and genuine darkness beneath it all. I am decoration, not great art. The graces of life, not the webbed philosophies, are my domain.”

Yet his writing is sharp, witty, and sometimes even raw, albeit opinionated, as a good journal entry should be. On seeing Nancy Reagan at the White House while accompanying the photographer Horst P. Horst, he writes: “She seems an empty vessel—but not one easily filled. … The basic image is moviemaking, and the movie from the start is strictly Grade B.” Watching Josephine Baker at Carnegie Hall in 1973, he describes her as “four feet and more of orange-red ostrich blooms on her head, like an Imperial Russian escaping across the wintered steppes—fleeing from the last imperial ball before the Bolshevik hordes!” Lerman was perhaps more of an artist than he thought, painting vivid pictures with wide but precise strokes.

Pascal, who came on as Lerman’s assistant at Vogue in 1981, writes that Lerman was fascinated by a person’s gestures, manners, styles, and affectations. He had a knack for summing someone up with a few quick strokes. Pascal rightly claims that the journal format, “impulsive, frank, unrevised,” was ideal for Lerman. In the end, none of his accomplishments could have been possible but for Lerman’s healthy self-respect as a gay man and a Jew. His two long-term relationships, the first with Richard Hunter and the second, much longer one, with Gray Foy, who was with him until the end, were accepted by his family and colleagues—no small feat in mid-20th-century America. Free to be who he was, Leo Lerman spread his own wings, and through these journals created grand surprises for the rest of us.

Christopher Lee Cochran is a freelance writer who’s based in Washington, D.C.