So many books of poetry have come across my desk that are worthy of comment that it’s hard to doubt we live in quite a remarkable time for poetry. Here are four books worth reading.

-David Bergman

Parthian Stations

Parthian Stations

by John Ash

Carcanet Press Ltd. 96 pages, $18.95 (paper)

John Ash’s new book is not “fiendishly gay/ (in both senses of the term).” In fact, he apologizes at the end for so many poems alluding to war and death, but that’s because he “could not,/ after all, misrepresent life,” and in our time the honest poet must acknowledge that “The corpse’s watch is still ticking.” Ash has been called the best English poet of his generation, and I have no argument with that assessment. He has the clarity, intellectual liveliness, and sad sense of history that one finds in the great Greek poet C. P. Cavafy. Now living in Turkey, Ash, like Cavafy, sits at the edge of an empire, at the corner of the Mediterranean, watching the Great Powers in their stupidity and greed grind up the lives not only of the humans they dedicated themselves to “protect,” but of the very cultures in whose name they destroy. The longest poem in this collection of rather short works is “Hotel Sefaris,” about searching out the home of yet another Greek poet whose world was destroyed by war.

Blackbird and Wolf: Poems

Blackbird and Wolf: Poems

by Henri Cole

Farrar, Straus and Giroux. 80 pages, $23.

I have followed Henri Cole’s progress, and even though the poems have never thrilled me, they have had a keenness and facility with language that held out the possibility of one day moving me. That time has come in Blackbird and Wolf. Not in all the poems: the opening section is a sort of grab bag of works that often overreach. The first poem, “Sycamores,” is written as a memory of being born. Cole doesn’t suffer the birth trauma but instead the Walter Pater-ish “hard gemlike feeling … like limbs of burning sycamores, touching/ across some new barrier of touchability.” Lovely, but I don’t believe it for a second. The concluding section, filled with well-intentioned anti-war poems, leaves me with only a sense of Cole’s good intentions. It’s the middle section that is truly beautiful and harrowing. In an unrhymed sonnet sequence, he relates how his lover of eight years first is hospitalized with depression and then commits suicide. In one of the best poems, “Poppies,” that perhaps alludes to Sylvia Plath’s own poems on the flower, he recalls waking “from a coma like sleep” and pausing so he can “say something true. It was night,/ I wanted to kiss your lips, which remained supple,/ but all the water in them had been replaced/ with embalming compound.” The moment is ghastly; the words “embalming compound” are harsh, a linguistic slap of reality that snaps the deadly suppleness of his poetry. When Cole stops his own fluency in order to mine the hard truths, he begins to write poems that live up to his capacities. In Blackbird and Wolf he has done so.

The Late Show

The Late Show

by David Trinidad

Turtle Point Press. 96 pages, $16.95 (paper)

I’m not sure what makes one David Trinidad poem feel heart-wrenchingly present and another that uses the same materials feel unoccupied. The book has two poems, “For Joe Brainard” and “Classic Layer Cakes,” heavily indebted to Joe Brainard’s endless list poem, I Remember. Both of these poems attempt to rise above the nostalgic to achieve the elegiac, but they lack either the wings that might carry them to such heights or the winds that might support them in the journey, and so, in the end they sound less like the catalogues in Whitman than like those at Sears: containing everything but what you came in for. Neither finds a way for the detritus of consumer culture to occupy that magnetic field that would grant them the psychic and literary charge they need. And just as I was unhappily putting the book down—unhappily because I so enjoyed his previous collection, Plasticville, and other fine poems in The Late Show—just at the moment, comes the concluding “Poem under the Influence,” which transcends its major influences, Schuyler’s Morning of the Poem and Ammons’ Garbage, and weaves from much the same material a profound, funny, and tender work. Perhaps this poem is so rich an achievement because it acknowledges, as well as resists, those who would forbid him to “extol the dark side of attachment,” and therefore he can cling to all the silly stuff that he has been collecting for so long in his heart, as well as see beyond to form a deeper connection to the world and the people he loves. It took Trinidad over a year to compose the thirty pages of “A Poem under the Influence,” but many would give their lives to produce a work so passionate, so dizzyingly spontaneous, so technically dangerous, and so moving.

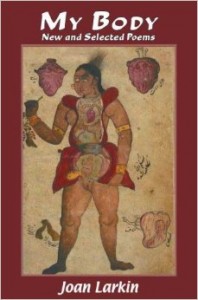

My Body: New and Selected Poems

My Body: New and Selected Poems

by Joan Larkin

Hanging Loose Press. 149 pages, $16. (paper)

There are few poets in America who can combine Joan Larkin’s formal mastery with her emotional intensity, and so it has been something of a mystery to me why she’s not better known or more widely valued as one of the finest poets in America. Unlike so many poets who lose emotional force as they get older, Larkin grows stronger as time goes on. The new poems in this volume are by far the best she has written. Perhaps Larkin’s failure to win a wider audience is the result of her tackling for many years a subject that men would like to claim as their own—alcoholism. If you put Franz Wright’s poems of drunkenness beside Larkin’s, it’s perfectly obvious who has written the better work. Yet Wright gets published by Farrar Straus and Larkin by Hanging Loose Press. But I think Larkin’s limited recognition also derives from something else. Larkin gives no place for the reader to hide, no easy consolations to cheer you up no matter how bleak things are. And things are bleak—but also joyous and mysterious—and you’d better get used to it and pay attention so that you can see that “Heaven is fire, too.” Unlike so many AA veterans, Larkin retains no belief in a higher power. As she writes in “Tough-Love Muse,” “Praise grief all you want,/ More loss is coming.” But Larkin deserves no more loss. The arrival of the recognition she deserves should be on the way.