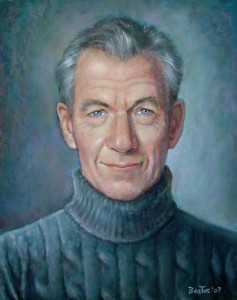

REVERED as one of the greatest actors of our times, Sir Ian Murray McKellen never felt he was doing his best work until he came out publicly at the age of 49. A private man who considered it nobody’s business what his sexual orientation was, McKellen kept mum about it until 1988, the year when Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher proposed her “Section 26” legislation, which would make the “public promotion of homosexuality” a crime. Invited to discuss the proposal on a BBC 4 program, McKellen used the occasion to come out as gay. In his 24 years of professional acting years before coming out, McKellen racked up 27 film and TV credits. In the nineteen years since 1988, he has amassed 48 film and TV credits as an older actor.

Born on May 25, 1939, in the town of Burnley in northern England, McKellen knew from an early age that acting was his calling. His parents encouraged him and took him to see plays,  particularly those by Shakespeare. Ian performed in school productions and attended Stratford-upon-Avon theatre festivals. In college he earned a B.A. in English Drama. Since then he has received an astonishing number of awards for theatre and film acting, with many more nominations. In 1990, Queen Elizabeth knighted McKellen for his contributions to the arts.

particularly those by Shakespeare. Ian performed in school productions and attended Stratford-upon-Avon theatre festivals. In college he earned a B.A. in English Drama. Since then he has received an astonishing number of awards for theatre and film acting, with many more nominations. In 1990, Queen Elizabeth knighted McKellen for his contributions to the arts.

Never one to slow down, McKellen afforded American audiences the rare opportunity to see him perform in two plays: as Lear in Shakespeare’s King Lear and as Soren in Anton Chekhov’s The Seagull, both at the Harvey Theater in New York under the direction of Trevor Nunn (this in addition to the release of two films in 2007, Stardust and For the Love of God).

In this interview, I spoke with the man who’s affectionately known around the world as “Gandalf the White” about Shakespeare, politics, coming out, and why he thinks the first Hollywood romantic lead to come out will be the most popular actor in the world. John Esther

G&LR: What is it about King Lear and The Seagull that have you coming back ten years later?

Ian McKellen: I haven’t played King Lear or Soren before. I’ve played Edgar and Kent in King Lear. I’ve watched a few King Lears at close quarters, having played the two. I remember it was a strain on the actors but it also brought out the best in them. I’m certainly finding it hard work, but that’s par for the course.

G&LR: How do these productions address larger concerns?

IMcK: I don’t think we chose to do them because we thought: this is the moment for the world to look at King Lear because he’s got something particular to say about the world’s situation. It is often true in Shakespeare that actors discover the plays are about personal relationships which reverberate down the centuries. They’re not plays stuck in the particularity of the time they’re written. We’re not doing King Lear because we think it reflects on the situation in Iraq or anywhere else. Those expecting that will find our production rather old-fashioned. Trevor Nunn’s production tells the story with clarity, and it’s up to the audience to take from it what they want. I’ve always thought of Shakespeare as a modern writer, and that’s true of actors throughout generations. He’s the greatest storyteller of all time. Anybody in Hollywood wanting to write a screenplay should study Shakespeare because Shakespeare did it better than they’ll ever do it. One never needs an excuse for doing Shakespeare. All the actors have to do is make sure they’re doing it with clarity, so that [despite]any difficulties people have with the occasionally archaic language they will be able to access the emotions, which, as I say, remain vibrant and modern despite the fact they were written 400 years ago.

G&LR: Yet the way plays are produced can suggest various political implications and representations.

IMcK: That’s not how I do Shakespeare. I don’t decide to use Shakespeare to boost my own views on anything. He knows a great deal more about human nature than I do. The challenge of Shakespeare is to present him with all his complications, all his subtleties, all the difficulties, all the contradictions, and for the audience to respond in whatever way they will. The fun of doing Shakespeare is to delve into all corners of it and present everything that is there and then have the audience respond. If I want to write a pamphlet, then I will write a pamphlet.

G&LR: Do you ever apply any of your own political considerations when you consider a role?

IMcK: If there were a play that seemed to be advocating something I didn’t approve of—like capital punishment or war as the answer to every political situation or an extreme right-wing view—then I would wonder whether I wanted to be in it. But if it were a good piece of storytelling, it probably wouldn’t achieve those very limited ends. I can’t think of a part that I’ve turned down because I didn’t approve of what the character was saying and often, of course, I play people one wouldn’t want to meet in real life. Like Iago in Othello or Macbeth. They do terrible things; they are murderers; they encourage other people to behave badly. A play advocating one simple point of view would be a very boring play indeed, and therefore I wouldn’t want to be in it. I’ve been in Martin Sherman’s Bent twice. I was in the original production in 1979 and I revived it ten years later at the National Theatre. That is a play I thoroughly approve of because it’s about what it’s like to be gay and it also discusses society’s prejudices against gay people. That wasn’t why I did it. It was a really good piece of storytelling and a challenging part. The play on the whole was expressing my own views, but I didn’t do it as a piece of agitprop.

G&LR: On a personal level, over the years which role did you find closest to you?

IMcK: Probably James Whale in Gods and Monsters, the English, gay director who, like me, was born in the provinces and went to London to get involved with theatre and was openly gay and came to Hollywood and enjoyed being there. I played him when I was roughly the same age as he was, so I could be sympathetic to his feelings. That is perhaps the part that is closest to my interests. I wouldn’t say I was like James Whale apart from the ways I just said. It’s often more interesting to play someone whose experiences and story are very unlike one’s own. Then you discover more about yourself and about other people as a result. When I came out and let it be known publicly that I was gay, a lot of people assumed that henceforward I would only be interested in playing gay characters. That would be extremely boring. Heterosexuality is far too interesting of a phenomenon for me not to be involved in that. I am playing King Lear, who is a great deal older than I am, whose experience of life is quite other from my own. To get inside yourself and imagine what it would be like to be somebody else is probably the major fun and purpose of acting.

G&LR: Can you think of any incidents in which being out affected your career?

IMcK: When I came out—as anyone who has had to go through that journey will testify—life improved. You gain as a person your proper self-confidence. You’re being honest and you’re standing up as yourself and for yourself. For an actor, to have that confidence is an immense bonus. On top of that I freed up my emotions, or at least my ability to express emotions without being circumspect, without lying, without this disguise. Acting is about telling the truth rather than lying. I improved as an actor. Maybe that’s why my career went positively in every direction and flourished and continues to do so. The commonplace assumption is that if you tell an audience that you’re gay they’re no longer going to be interested in you as an actor. I found absolutely the opposite. The public doesn’t give a damn about an actor’s sexuality. They care about his talent.

G&LR: Which may not always be the case. Why are audiences more tolerant when it comes to the sexuality of performers than other public figures?

IMcK: If a politician announces he or she is gay, that is not how he or she will be judged. They will be judged on how well they do a job as a politician. It’s the same for a priest, a schoolteacher, a scoutmaster, a mother or a father. What someone does in private may be of interest to the public, but because you’re in public life is not to say that everything about you needs to be delved into and considered before the work that you do. If you look at a painting, the first thing you ask isn’t the sexuality of the artist. It’s not to the point. The same is true with any job you do. Now people have a personal relationship with actors, or they think they do, but what they’re relating to of course is the public persona—what is presented to them. Therefore, it is of no interest to me to consider the sexuality of an actor on the screen who I respond to and enjoy and am sympathetic to. I might have a fantasy about it, but I’m not in the world of fantasy. I’m in the world of truth. I’m in the world of trying to explain what life is like. That may be the confusion in some people’s minds in Hollywood. Hollywood is probably a great deal more about the world as it is not than the world as it is. Hollywood tends to exaggerate and fantasize about life. I’m speaking very generally. Even when I’m in a fantasy film like Lord of the Rings, what interests me about it is the reality of the characters, not the fact that they’re going to fight monsters and so on.

G&LR: Along these lines, why is it easier for England’s actors to come out than it is for actors in Hollywood?

IMcK: The fear is probably that if you’re marketing your film—whether it’s on TV or the big screen—in the United States, you have to be careful with the areas of the country where audiences have strong prejudices against gay people. It’s a question of marketing. They think their TV program is going to lose its advertising because there’s an openly gay actor in the script, and somehow audiences in various parts of this large nation might not want to go see them. It’s a bit of bafflement to me. In Hollywood there are openly gay producers, directors, designers, scriptwriters, agents, and managers, and the only area where there seems to be some reluctance to come out is among actors. They’re taking very bad advice from their advisors. The first young actor who’s hugely successful in romantic roles who comes out and says he or she is gay will overnight become the most famous actor in the world, and their career will continue to flourish. We’re very close to that now.

Mind you, there are people in Iran being hanged if they make love, and it’s a wicked world. And we’re in a period of flux and change in the Western world. Even if the laws change—as they have done successfully under the Blair government in the UK—that doesn’t mean that attitudes in the public at large will change as rapidly. There was a man murdered last year in a public place in England simply on the grounds that he was gay. People say it’s difficult for actors to come out in Hollywood. It’s difficult for priests, politicians, teachers, and everybody. It isn’t particularly a problem for actors.

G&LR: Your life seems to consist mostly of acting. What other interests do you have outside of the stage and screen?

IMcK: Acting isn’t like making furniture. Acting is about what it is to be a human being and life itself. I’m constantly delving into other peoples’ lives when I play the part. It isn’t a pastime. It’s not just work or a hobby; it’s all-embracing. I don’t have a need to get back to what I most enjoy, which is being inquisitive about human nature, life, and politics. That’s all satisfied by acting. I enjoy walking in wild places, traveling, reading, and getting involved sometimes in politics, but my abiding interest is getting better as an actor, and that’s a journey that never ends.

G&LR: Finally, what do you think about these interviews where you discuss yourself and your work? Do they serve the work or should the work speak for itself?

IMcK: It seems that if people only know me from articles they’ve read or interviews I’ve given that I love talking about myself. It’s not what I do all day long. It would be lovely never to have to give an interview, because sometimes you find yourself over-analyzing yourself or making a case you don’t totally believe in. I haven’t written a book about acting or an autobiography, and I don’t intend to. I would rather just be known as an actor and for people to come see me at work.