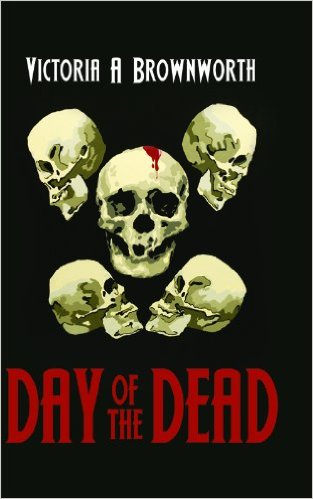

Day of the Dead and Other Stories

Day of the Dead and Other Stories

by Victoria A. Brownworth

Haworth Press. 190 pages, $14.95 (paper)

“FOG HAD ALWAYS held a dangerous allure for her. She was drawn to it, yet knew within its smeared edges and blurry recess there were things she didn’t want to see, things she shouldn’t see. She knew that the fog was the bridge, the hazy portal between the world of the living and the habitation of the dead.” This passage from a story, “Diary of a Drowning,” explains how a kind of representative character, a lesbian documentary filmmaker with an anxious lover in another city, has been seduced by New Orleans, and why she fails to escape in time to survive Hurricane Katrina.

This passage could also serve as an introduction to all seven of the dark tales in Victoria Brownworth’s latest collection of fiction. Each one can be read as an exquisite eulogy for those who don’t survive the disasters of our time—unless they become vampires or succubi. Reading these stories could lead one to believe that immortal predators move among us, representing hope as well as danger.

The author’s experience as a journalist has clearly given her firsthand knowledge of real tragedy as well as an urge to comment on it in various genres. Life in these stories is bleak, and not only for the lesbian central characters. In the title story, “Day of the Dead,” a young Irish student, drawn to New Orleans (apparently pre-Katrina) by an older academic lover, finds herself homeless, friendless, and suffering from mysterious ailments. She is diagnosed with AIDS and feels death approaching, but she learns that help can arrive when one least expects it. Her life will never be the same, but by the end of the story she’s looking forward to the next sunrise and to her lover’s return.

The lure of the fatal city is one of the recurring themes of this collection. In most cases, the city is New Orleans, but it can be any cultural center that draws the young and the restless (especially lesbians) from former colonies (such as India) or slums (such as those on the outskirts of Moscow) or the American backwoods. In “Twelfth Night” (named for a holiday once widely celebrated in Europe and England as the climax of a 12-day Christmas), a celebrated journalist returns to New Orleans from various war zones to reunite with old friends and tell them the secret of her survival. In a related story, “St. Lucy’s Day,” a young Swedish woman feels she must choose between the city she loves (New Orleans) and the woman she loves, who has returned to her own siren city. The luminous Swede meets a charismatic Mexican woman on the feast day of St. Lucy, named for a teenage virgin martyr of the fourth century who’s associated with the healing arts, with faith over the fear of death, and with the expectation of returning light on the winter solstice.

Lesbian eroticism pervades most of these stories, though there are few explicit sex scenes. The central characters’ desire for carnal knowledge with the women who attract them is inextricably linked to their desire for a sense of rootedness and for a little peace and justice. The fulfillment of desire is shown to be a miraculous reprieve from the random violence of the world.

The supernatural elements in these stories are so well integrated with realistic plots that the reader is constantly reminded that reality as it unfolds is often different from what we ever imagined possible. The fate of New Orleans in September 2005 is one example of this, as Brownworth explains bluntly in a final author’s note: “Wraiths and demons, vampires and succubi stalk these stories. But the vampires that sucked the blood from New Orleans were a President, a FEMA Director, a Homeland Security Director, and an Administration that had so little concern or compassion for hundreds of thousands of people in one of the most beautiful and compelling cities in the country, that they let the city drown and the people with it.”

An element of advocacy journalism is apparent here as in the rest of these grimly beautiful stories. As she has in previous novels and short stories, Brownworth proves that it is possible to use fantasy fiction as a vehicle for telling the truth.

____________________________________________________________________

Jean Roberta is a widely published writer based in Regina, Saskatchewan.