THERE’S SOMETHING RAPTUROUS about watching fabric spin so fast that discrete shapes dissolve into the blurred trails of after-image. Even a few seconds of watching a gifted flag dancer are enough to flip a switch in your mind, unhooking part of your consciousness; it’s the outer border of trance.

Born about thirty years ago in the gay clubs of San Francisco and Chicago, flagging—which is also known as fanning, spinning linen, or rag dancing—has migrated across the United States and as far away as Australia and Brazil. Despite its  increasing popularity though, it has remained a private art form, flourishing mainly within the confines of a subset of the gay community, where it lives as both a performance genre and a dance floor phenomenon. That is, flag dancing can be a spectacle, taking place on a stage or raised platform; or it can be a spontaneous expression of individuals at a dance who take out their own flags to dance alone or in groups. Sometimes, both happen at once: a flagging performance inspires those in the audience to join in, casually erasing the boundaries between performers and spectators.

increasing popularity though, it has remained a private art form, flourishing mainly within the confines of a subset of the gay community, where it lives as both a performance genre and a dance floor phenomenon. That is, flag dancing can be a spectacle, taking place on a stage or raised platform; or it can be a spontaneous expression of individuals at a dance who take out their own flags to dance alone or in groups. Sometimes, both happen at once: a flagging performance inspires those in the audience to join in, casually erasing the boundaries between performers and spectators.

But for those deeply involved in it, flagging is no casual pastime, provoking comparisons with meditation, intoxication, and the most soulful, fulfilling sexual encounters. “It can be a very introverted, contemplative thing,” says television producer and flag dancer Brad Carpenter, 46, who has co-founded a professional flagging troupe, Axis Danz. “These loops you make and unmake—the repetition—can create a trance-like state. You can open up your perceptions and feel the flow.” One of the few women practitioners of the genre, Candida Scott Piel, who also teaches flagging, sees it as part of a nearly mystical guild: “It’s a piece of gay culture,” she says, “that takes you very deep. Like any movement-based spiritual practice, such as Tai Chi, it produces an altered state of consciousness, in which the left and right sides of the brain are synchronized.” (Piel represents a number of lesbians who took up flagging in the 1980’s, in a sisterly attempt to protect it when AIDS threatened to render the male dance community extinct. Recent medical advances and the resultant improvement in many men’s health have shifted flagging back again to the men’s domain, with few women practitioners left.)

Unsurprisingly for something this emotionally charged, flagging also seems to incite political turf wars, especially in recent years as it has begun to cross over into the mainstream cultural arena, popping up in music videos, sharing the bill at charity benefit performances, and even serving as the floorshow at bar mitzvahs. Some fear that such commercial exposure cheapens flagging and risks stripping it of its special expressivity and connection to gay culture. Others argue that gay culture need not be guarded so jealously, since it has always provided material for the mainstream (remember voguing?). But flagging is an especially potent art form with powerful psychological effects. Its roots, I believe, reach back thousands of years in dance history. It is likely therefore to have a more powerful impact on popular culture than the typical dance club fad that vanishes in a year or two. Flagging, as I shall demonstrate, is a liminal art form experiencing a liminal moment in its own history.

Essentially, flagging consists of rhythmically spinning rectangular fabrics, usually silk, which are often dyed (sometimes tie-dyed by hand) in rainbow colors with undulating designs. These fabrics can be attached to long poles—like military flags—weighted along the edges with curtain weights, or ribbed like large fans. The dancer sets the fabric in motion through consistent, circular, and sweeping motions of his arms, which often trace large figure-eights through the air. When done correctly, the flags rise and fall with the air currents, inflating momentarily into three-dimensional, funnel-like shapes. They seem to spin of their own accord in a whirl of motion around the dancer, becoming a translucent nimbus of color that pulses with the music, alternately covering and revealing different parts of the body. A very large flag might even drift down over a dancer’s face and upper torso, obscuring his identity momentarily. Dancers perform fully dressed or, often, bare-chested. Given their prevalence on the rave circuit, club drugs, such as Ecstasy or crystal methamphetamine, have also figured in the history of flagging, enhancing both the trippy visuals of the dance and the hypnotic sense of well-being it can create.

For some, however, flagging is itself drug-like, but in a salubrious way, offering an alternative to more dangerous mind-altering experiences. As the fabric whirls into the air, participants feel lifted out of their bodies, finding normally inaccessible emotions and thoughts rising effortlessly to consciousness. Chris Ofner, a flagger in his late fifties who calls himself an “old hippie” and brings his own hand-dyed flags to parties, abused drugs and alcohol in his youth. “Flagging saved me,” he says. “I’m sober now for twenty years. The flags provide a kind of meditation for me.” Choreographer and psychotherapist George Jagatic, co-founder with Carpenter of Axis Danz, offers a similar conversion narrative. Having first encountered flagging during his own drug-fueled younger days of clubbing in San Francisco, Jagatic found that flagging made him feel curiously sober even when stoned. “The experiences I had doing this were so profound that I had to figure out what it was. It was so healthy. I was high as a kite and it would ground me, pull me out of my high. I felt clear.” Jagatic who, like Ofner, has given up drugs and alcohol completely, describes flagging as a “transfixing experience that takes you out of your body, while putting you into the moment without baggage.”

The origins of flagging can be found in a number of dance forms, particularly certain traditional Asian dances. The trance-inducing spinning recalls, for example, the famous whirling dances of Sufi dervishes. And flagging’s reliance upon an undulating, hand-held object to enhance movement and create a hypnotic effect links it historically to the ancient Japanese kagura dances, which have been performed since at least the eighth century. Kagura rituals, particularly in their folk incarnations (as opposed to those dances performed for royalty), involved possessional dances, performed by Shinto shamans of both sexes with the aid of hand-held objects, or torimono. Benito Ortolani writes in The Japanese Theatre (1995): “The kami [deities]were believed to reside in the objects held in the hand (torimono) of the shaman: sakaki tree branches, paper pendants, pine branches, bamboo, sword, willow.” The torimono symbolically extended the human body into the divine realm and served as channeling devices through which the kami might enter the shaman’s body and induce trance.

Flagging, especially when it uses smaller, internally ribbed fabrics, also finds a striking historical predecessor in Asian fan dance, in which the fan can be used symbolically to convey a variety of dramatic meanings. Often these meanings convey a sense of liminality, of crossing from one realm to another—much as in possessional dance in which the human crosses the threshold of divinity. In Japanese noh drama, for example, a character might hold his fan across his face and peer through it to indicate that he is looking through a window. Similarly, in Chinese opera, a character might use the floor-length sleeve of his costume like a fan, drawing it across his face to indicate that he has become invisible.

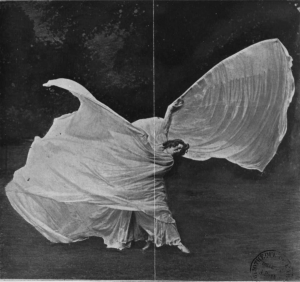

Flagging also resembles some more recent genres. Early 20th-century dancer Loie Fuller enjoyed international fame for over thirty years dazzling audiences with her cross between the Asian fan dance and a Middle Eastern danse du voile. Attaching silk robes of up to 300 square meters to flexible batons, Fuller spun these vast veils into Art Nouveau visions of lilies, butterflies, or ocean waves. Like the flagger’s flowing tie-dyed silks, Fuller’s whirling fabrics often lulled spectators into states of near hypnosis. (“[She] tears us away from … everyday life and leads us to purifying dreamlands,” rhapsodized one critic at the time.)

While Fuller maintained a modest demeanor onstage and never disrobed, she was clearly borrowing from a long tradition of more raunchy adaptations of fan and veil dances. The most famous fan dancer of the 20th century, Sally Rand, used her large feathered fans to play a sophisticated game of peek-a-boo with the audience, encouraging spectators to believe they had seen glimpses of nude flesh that in fact had never been revealed—for she never completely disrobed. Rand illustrates perfectly Roland Barthes’ observation in Mythologies (1972) that “there will be … in striptease a whole series of coverings placed upon the body of the woman in proportion as she pretends to strip it bare.”

Whether used to summon the divine, sculpt ephemeral forms, or titillate the spectator, the dancer-with-object represents a desire to go beyond social limitations, be they religious, physical, or erotic ones. Flagging belongs squarely within this tradition. Most basically, this is simply because the hand-held object always extends the body into the wider space around the dancer. This extension of the self helps make the connection between the sacred and profane versions of the object-dance. Just as the shaman’s torimono acts as a mediating object with the divinities, so does the stripper’s mobile fan or veil mime the opening and closing of the door between the public and the private, the social and the sexual, the clothed and the naked (and even the very mechanical in-and-out motion of intercourse itself). Flagging exists precisely in this zone of in-betweens. As the flags rise and fall, obscuring or revealing the dancer’s body, they reenact the oscillation between the individual and the collective, the frank assertion of identity and the obscuring of it.

One cannot discuss flagging without also acknowledging its charged and ambivalent relationship to gender. Like its ancestor, the fan dance, flagging incorporates certain graceful, flowing movements understood culturally to be deeply female, as well as other movements classically associated with masculinity. Waved in slow, fluttering circles, flags or fans can suggest the soft curves of a woman’s body and a teasing, feminine coyness. But raised and held aloft, or aggressively thrust upward and away from the body, the same implements exaggerate the dancer’s power and size, evoking the muscular force of a warrior menacing an enemy or of a bird of prey poised for flight.

This iconographic richness and sexual ambiguity help explain how flagging came to be a mode of expression in the gay male community; more gracefully and succinctly than drag, it performs the mutability and theatricality of gender roles while emphasizing the fluid connections among them. A flagger can slip easily from feminine, even effeminate fabric waving to a more aggressive, macho display of physical strength. Candida Scott Piel aptly evokes both flagging’s gender playfulness and its likely Asian provenance in her description: “In a flick of a wrist, you go from Madame Butterfly to a samurai.”

But flagging’s appeal to the gay community stems not only from its gender ambiguity but also from its ability to assert symbolically both collective and individual identity. Flags, after all, are badges of identity; when displayed on battlefields, on ships, or at sporting events, they declare the presence of a nation, a tribe, a team. The language of flaggers consistently reflects this view: in conversation and in their many website chat rooms, practitioners refer to themselves as a community, a subculture, or most often as a “tribe”—a word suggesting a yearning to recreate the extended familial bonds so many gay men have had to sever. (The most popular website and chat group for dancers is known as “spintribe.”) Sometimes this tribe is divided still further into “flaggers” and “fanners”—distinguished by the size and shape of the fabrics used.

George Jagatic sees flagging as the expression of a ghetto-ized, closeted community struggling with becoming visible to others: “Signaling is a key word here. As gay people we’re shunned; greater society does not want to see us.” In their covering and uncovering, the flags create an image of being at once inside and outside, in the closet and wanting out—with all the anxiety that this implies. When practiced among friends or even strangers on a dance floor, flagging can also weave intimacy and solidarity on a small scale, as flaggers riff off one another’s movements, turning a solitary act into a partner or group dance. “You can pick up someone’s energy and pass it back and forth,” explains Carpenter.

Flagging perpetuates itself via a kind of sacred guild in which apprentice flaggers learn from masters or the (more familial) “flag daddies.” And it is true that, with rare exception (Jagatic runs occasional classes in New York City), flagging is still learned informally. The process of transmission generally consists of an entranced spectator asking a flagger to show him how it’s done. Carpenter refers to this ritual as “asking for and receiving the gift.” For him, the flagger has an obligation to teach anyone who is moved to ask, to pass on this gift in a ritual exchange. At New York City’s Gay and Lesbian Center one winter night, just such an exchange occurred right after Jagatic had taken the dance floor with his flags to perform an impromptu but bravura solo. I had gone to an open dance at the center, having been told it was a receptive venue for spontaneous flagging. In the crowd, Sean Byrne watched Jagatic, mesmerized. He had never seen flagging before. When Jagatic had finished, Byrne, 38, rushed up to him asking to be taught the basics of flagging. When I asked him what had moved him so about the performance, Byrne said he wasn’t sure, but that “something had happened” to him. Looking dazzled, yet a little embarrassed, he said, “Can I say it was like sex? Like a wave, like a butterfly?”

Byrne managed to conjure all of the tropes that tend to arise around flagging: images of the sea, of sex, and of something larger than oneself drawing one in in wave-like motions. His sense of having been intermittently lost to the spinning fabric echoes every “first-time” flagging story I have heard, including that of psychoanalyst Daniel Sibony, who writes: “In a trance … it is the alternating movements in which the body is abandoned-returned, lost-found, perceived-remembered. … Like the alternating rhythm of breathing (inhale-exhale), one arrives at a sort of orgasm—absence or little death, thereby called trance” (in Le Corps et sa danse, 1995).

Although flaggers tend to focus on the unifying power of their art, which they describe in the language of intimacy, kinship, and solidarity, the genre can also spark social conflict. At the Gay and Lesbian Center, a number of men expressed disgruntlement when the flaggers took the floor. Flagging, one told me, is “too individualistic and makes a spectacle” of the individual dancer. “Flagging takes up a lot of room,” another pointed out. “You have to give these guys at least six feet in every direction.” And this is true. Like the whirling propellers of a jet on a runway, flags in motion require a wide safety zone, which on a crowded club floor amounts to prime real estate. Gay icon “Rollerena,” the roller-skating, drag-queen Vietnam veteran and anti-war activist, told me that s/he had never really enjoyed flagging precisely for this reason: “They’d arrive on the floor and everyone would have to stand back,” s/he said.

While flagging can be a narcissistic display, as when buff, bare-chested men climb atop boxes and spread their fans like so many peacock feathers, it seems largely a forgiving genre, offering less perfect male specimens a kind of beautiful prosthetic body-in-effigy—the ribbed or weighted silk providing a graceful, floating substitute for the flesh-and-bone, earthbound body that wields it. “Charlie,” a fairly corpulent flagger in his late twenties whom I met one night on the dance floor, stripped down to just his briefs and climbed onto a pedestal to flag with abandon, his eyes closed, face upturned. His generous belly gyrated along with the fabric, but Charlie was unconcerned; he looked beatified, lost to the moment in a kind of swoon.

The feeling of abandon many people describe may also arise from the fact that waving fabrics follow the ambient air

currents as well as the direction of one’s arms. Flagging provides a slightly uncanny randomness. You never know exactly where the momentum will propel you; and this unknowingness reinforces the sensation of being “taken over” by an outside force—a fundamental part of possessional dance. “Your body becomes sort of possessed,” observed Brad Carpenter. “You don’t know what’s coming. The fabric gives you another energy, but it’s also a bit of a wild card. It’s an energy you try to control”

If flagging does make the transition to the general population, it is likely to be as a regulated form of entertainment and an art learned in studio classes. George Jagatic, while fully cognizant of flagging’s deeper, mystical qualities, intends to promote such a transformation. As a professional dancer, Jagatic has studied and codified the basic movements of flagging, giving them names such as “butterfly” and “windmill.” In his classes, his instructional DVD, and with his performance troupe, he is slowly standardizing flagging. For him, these steps are necessary to ensure its survival as a serious, teachable art form. Jagatic and his colleagues are at the forefront of flagging’s emergence from the gay subculture.

At the moment, Jagatic and Carpenter’s company, Axis Danz, consists entirely of women, most of whom come to flagging from traditional ballet, jazz, and modern dance backgrounds. The company’s choreographer, Jennifer Carlson, has injected a particularly elastic and ethereal quality into the movement. Recent pieces have also played with the scale and shape of the flags, including one that made use of an enormous Maypole-like structure out of which flowed multiple twenty-foot ribbon streamers which the dancers held, sculpted overhead, and wound around their bodies. The effect suggested a cross between the rhythmic gymnastics of the Olympics and Japanese kagura dances.

Flagging is now showing up in Mariah Carey videos and at pool parties in the Hamptons, raising the question of whether this private art can become a public form of entertainment and retain its potency. It may be that flagging’s particular blend of gay identity politics, hypnotic seduction, and safe intimacy will prove untransferrable to the general public. Flagging began as a burst of colorful self-expression within a group that felt itself invisible and silenced. It belongs to an earlier era of gay pride and political activism and came on the heels of the feminist and civil rights movements, both of which were salient at the time in popular culture—in television, music, and film. In our own times, though, progressive politics and mass culture seem to live on separate planets. But should we be ready for a change, should average citizens start yearning once again for a deeper state of awareness or more meditative pastimes, perhaps flagging won’t lose its ancient, hypnotic force but instead catch on like wildfire.

Rhonda Garelick, a performance studies scholar and professor of French at Connecticut College, is the author of Electric Salome: Loie Fuller’s Performance of Modernism (Princeton, 2007)