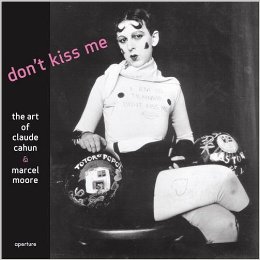

Don’t Kiss Me: The Art of Claude Cahun and Marcel Moore

Don’t Kiss Me: The Art of Claude Cahun and Marcel Moore

Edited by Louise Downie

Aperture. 240 pages, $45.

IN THE AUTOBIOGRAPHY of Alice B. Toklas, Gertrude Stein’s recounting of her expatriate life in Paris before World War II through the eyes of her lover, the narrator notes that they were “in the heart of an art movement.” This movement included young writers and painters such as Hemingway, Matisse, Picasso, and a host of others who crowded into Stein’s salon at 27, rue des Fleurus, to discuss the ideas and æsthetics of what is now called Modernism. Outside Stein’s salon, there were other corners of this movement where creativity and sexual politics were even more keenly felt. In Louise Downie’s Don’t Kiss Me, we encounter one of these corners.

Hidden from history until the early 1990’s, Claude Cahun and Marcel Moore resist easy categorization. This book, which is part biography and part art history, is the first book in English to explore the range of their creative and political lives. Cahun was born Lucy Schwob in 1894 in Nantes, France, to a wealthy publishing and literary family. Her father and grandfather owned and edited the regional newspaper, La Phare de la Loire, and her uncle Léon Cahun wrote historical novels and was involved in Paris intellectual circles. Through much of her childhood, her mother suffered from depression and flirtations with suicide, leaving the young Cahun to find solace in her father’s library, where she read works of philosophy, art, and literature. Her first unpublished manuscript, “Les Jeux Uraniens,” a semi-autobiographical book crafted through a collage of descriptive narratives, marked the first time the young Schwob used the pseudonym Claude Cahun. According to Kristine von Oehsen in her biographical essay in Don’t Kiss Me, the name holds a “strong reference to her paternal lineage and Jewish background” and “testifies to her reluctance to ascribe to either of the strictly binary gender roles; instead she opted for the androgynous.”

It was at school in Nantes that Cahun met Suzanne Malherbe, the daughter of a professor at the Nantes School of Medicine and a member of the city council. Malherbe studied art and design and, when she began publishing illustrated articles about fashion in Le Phare de la Loire, she took an alliterative cue from Cahun and adopted the pseudonym Marcel Moore. In their early years together they experimented with photography, beginning a life-long fascination with the theatrics of gender and photographic portraiture. In 1919, just two years after Cahun’s father married Moore’s mother, the two published a book titled Vues et visions, a collection of homoerotic drawings, poetry, and meditations inspired by their interest in classical myths and philosophy. “This album’s publication could be viewed as Cahun and Moore’s artistic coming out,” notes Tirza True Latimer in her essay on their collaborative efforts, “since it undoubtedly raised their public profile as an artistic couple and affirmed (albeit in code) their affection for each other and the legitimacy of their bond.”

In 1922, the two arrived in Paris and landed in a milieu of artists and intellectuals. Cahun took up acting and was a founding member of an avant-garde theater group. She published, with Moore, Aveux non avenues, a surrealist collection of meditations and photo-collages. By the 1930’s they became active in communism and surrealism, seeking a more engaged role as artists in such groups as the radical Association of Revolutionary Artists and Writers. In 1934, she published Les Paris sont ouverts, a political tract that would later influence André Breton. Cahun and Moore were in many respects as much shaped by the artistic and political ideals of the 20’s and 30’s as they were by the emerging theories of gender and sexuality. Cahun was the first to translate Havelock Ellis’s theories of homosexuality into French.

By the late 1930’s, with the Nazis marching toward Paris and Cahun quite disillusioned by the failure of the political agenda of the surrealists, she and Moore moved to the island of Jersey off the coast of France, which is where the two had often spent their summers. Yet their retreat was short-lived, for the Germans invaded the island in the summer of 1940 (the only part of the UK the Nazis occupied), and Cahun and Moore, using their birth names again, remained in Jersey in a defiant choice to resist the Germans, believing that war was “the most drastic regression” from revolution. As Claire Follain notes in her essay in Don’t Kiss Me, they worked as a two-woman resistance movement, crafting anti-Nazi tracts in German and “deposit[ing]the notes in soldiers’ coat pockets or on tables” without being detected. But they were detected, in 1944, arrested, tried, and sentenced to death. The liberation of the island in the spring of 1945 saved Cahun and Moore from execution and freed them from prison after nine months. They lived out their lives in relative seclusion in Jersey for another nine years, until Cahun’s death in 1954. In 1972, Moore ended her life at the age of eighty.

The second half of Don’t Kiss Me is a catalog of the Cahun and Moore collection at the Jersey Heritage Trust. The catalogue provides a range of images from portraits and photo collages by Cahun to the beaux-arts drawings of Moore, and photographs of friends and family. It would be a stretch to define much of the photography as art, for it documents more than it imagines. The real intrigue, however, rests in the portraits, which have become central to the revival of Cahun over the past decade. Most are quite dramatic and performative, reflecting a number of influences, including surrealism, avant-garde theatre, gender and sexual theories, and psychoanalysis.

In one early image from 1916, Cahun, dressed in a white-collared shirt and suspenders, her head shaved, stares passively at the camera, exuding a toughness against a hard stone wall. Contrast this image to the one of a preening, feminine Cahun, wearing thick make-up and a tight blouse that reads “I’m In Training. Don’t Kiss Me.”—but training for what? In one of her better-known photographs, she stands sideways, turning slightly to address the camera, hair short and bleached blonde, lips rouged, her hands pulling at the collar of a checkerboard-patterned coat. Her head leans against a narrow mirror offering a double vision of her face. The image is a striking play of androgyny that seductively transforms the subject of the photograph into a question. For Cahun and Moore, their photographs were done for personal pleasure. Indeed, the portraits were never published or displayed but instead served as a kind of private theatrical arena of identity.

While forgotten for decades, the first retrospective of Cahun’s work was mounted at the Musée d’Art de la Ville de Paris in 1995, inspiring the exhibit “Inverted Odysseys” in New York and Miami four years later, which featured Cahun’s work alongside Cindy Sherman and filmmaker Maya Deren. Increasingly, critics have discussed Cahun’s work as a predecessor to such contemporary artists as Sherman and Nikki S. Lee, whose self-portraits play with our cultural beliefs about the stability of identity. Yet Cahun’s revival has often been defined independently of Moore. “What social prejudices and artistic hierarchies does the erasure of Moore accommodate?” asks Latimer in her essay. And this is perhaps one of the book’s strongest points: to look at Cahun’s portraits is to see an exchange between two lesbian artists whose life together illuminated their political and creative visions.

James Polchin teaches writing at New York University. He is completing a book on the life of George PLatt Lynes.