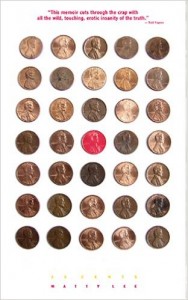

35 Cents

35 Cents

by Matty Lee

Suspect Thoughts Press. 205 pages, $16.95

IN THE WAKE of the recent scandal surrounding the popular yet fraudulent gay author JT LeRoy—not to mention the Oprah Winfrey-fueled outrage over James Frey’s fabricated tale of drug addiction, A Million Little Pieces (2005)—the question of truth and authenticity in a nonfiction literary work has acquired a new urgency. Given the current climate, first-time writer Matty Lee’s no-nonsense, hyper-real memoir 35 Cents, which chronicles Lee’s days as a straight boy who was rapidly inducted into the world of gay hustling in southern Florida at the tender age of thirteen, arrives at an opportune time, prompting some intriguing questions of its own. What exactly makes a “true story” real or authentic? Should a text’s sensationalism or immediacy always be approached with a degree of skepticism? What responsibility does an author of nonfiction have, morally or otherwise, to portray supposedly real events authentically? Allowing for some inevitable embellishment, what should be the limits of artistic license?

If his book itself is any indication, Matty Lee may not be too seriously invested in exploring such philosophical questions. Instead, 35 Cents careens along at breakneck speed, capturing its narrator’s youthful energy, his sexual confusion, and at times his intensely unglamorous disorientation. While one gets the feeling that Lee’s own inner voice has matured enough to give him some perspective, the protagonist often sounds stubbornly childlike and clueless, making it all the more heart-rending when a moment of clarity breaks through the haze of tricks, drugs, and hardcore street life. “The girl I would never have, the car I would never drive, the house I would never live in, the life I would never lead,” Matty thinks to himself as he gazes at the idealized magazine photos that he’s arranged on the walls of his room in a juvenile rehabilitation clinic. Because so much of Lee’s book remains straightforwardly gritty and purposefully unadorned, it also raises the question of the importance of artfulness in a work of creative nonfiction. However detailed a mental notebook he might have kept, Lee couldn’t possibly recall with exactitude some of the scenes and characters that he came across during his time hustling, nor should we necessarily want him to. The fast-paced parade of younger and older faces, clothed and unclothed bodies, innocent and wild fetishes, assumed and actual names, are meant to endow Matty’s encounters with a kind of legendary aura. In this sense, 35 Cents most closely resembles John Rechy’s gay hustling classic City of Night (1963), in which many of the chapters are also named after the narrator’s tricks, a living historical document of figures, places, and moments that the author eventually realizes he can’t and shouldn’t forget. This realization underscores the central, provocative lesson of Lee’s memoir: that a young straight kid can discover some of the hidden, essential truths about life via older men who either pay him money or hit him up for sex. In a moving scene during which Matty recalls the last days of Jules, one of his closest friends who also happened to be his Narcotics Anonymous sponsor, Jules tries to reach gently into Matty’s pants as they sit together on his hospital bed, despite the fact that Jules has almost no energy left from battling AIDS. Matty, the impulsive teenager, is so startled by the gesture that he leaves the hospital and doesn’t return. Understanding his mistake a few days too late, Matty wonders, “Was it so sick and perverted that we both wanted to be touched? Did he deserve to die because of his longing? Did I? Did anyone?” Appropriately, 35 Cents culminates in Lee’s enlightenment and redemption through an innovative spiritual twist that, for the purposes of reading pleasure, cannot be completely disclosed here. Let’s just say that an ending that might have come off as trite (and perhaps does border on the trite at times) instead feels almost exquisite in its resolution. Although Matty Lee may not find love with another man, ultimately, he does become aware of the possibility, while also learning that identifying himself as straight or gay or bisexual may not matter all that much, especially since the very decision not to identify his sexuality specifically has allowed him to live such a varied, occasionally reckless, and memorable life. Jason Roush, who teaches at Emerson College, is the author of two books of poetry, After Hours and Breezeway.

____________________________________________________________________