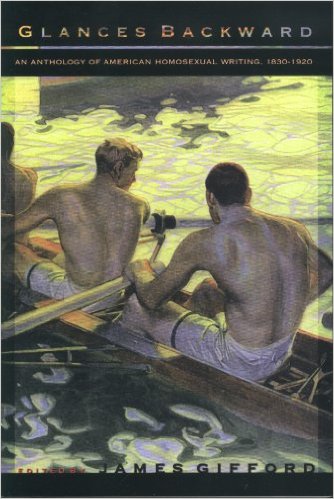

Glances Backward: An Anthology of American

Glances Backward: An Anthology of American

Homosexual Writing, 1830-1920

by James Gifford

Broadview Press. 385 pages, $22.95 (paper)

THANKS TO THE INTERNET, we can now go to Google Books and find the full text, cover to cover, of such proto-gay novels as Shirley Everton Johnson’s 1902 The Cult of the Purple Rose, Bayard Taylor’s Joseph and his Friend (1870), and Charles Flandreau’s 1897 Harvard Episodes—just to mention three of the books excerpted in Glances Backward. Gifford, author of the excellent Dayneford’s Library (1995) and a scholar of the writer and critic Edward Prime-Stevenson, whom he quotes frequently, has collected about fifty American writers of prose, poetry, and nonfiction, excerpted some of their most telling works, and provided a well-written introduction that instructs the reader on how to read between the lines, remembering to notice bookplates and dedications.

Each entry is prefaced with explanatory notes and ends with many references and well-chosen sources for further reading, making it obvious that this is a work targeted at gay studies programs, but it will be enjoyed by anyone interested in the field. Granted, these texts are being offered for their historical interest rather than their literary value, but some readers might find it difficult to read prose such as the following, which comes from Charlie Codman’s Cruise; or, A Young Sailor’s Pluck, an 1866 novel by Horatio Alger, Jr.: “‘No, Bill Sturdy,’ he [Charlie Codman] said manfully. ‘I don’t want you to suffer in my place. It’ll be hard to bear it,’ and his lip quivered; ‘but it would be weak and cowardly for me to let anybody else suffer in my place.’”

Gifford is careful to be as culturally inclusive as possible, given the constraints of his time period. Among the writers chosen are: Navajo elder Slim Curly, for his narration of a berdache myth, dictated to a sociologist; the complete short story, “Paul’s Case” (1905), a classic by lesbian writer Willa Cather; and an excerpt from The Autobiography of an Ex-Colored Man, a 1912 novel by James Weldon Johnson. This was certainly not the expected choice, since, as Gifford notes, the first openly gay story by an African-American writer was Richard Bruce Nugent’s “Smoke, Lilies, and Jade” (1926). The Autobiography—written as a satire—was about a young musician passing for white in Europe and his older, wealthy patron. Curiously enough, another literary anthology, 1998’s Pages Passed from Hand to Hand: The Hidden Tradition of Homosexual Literature in English from 1748 to 1914, edited by David Leavitt and Mark Mitchell, covered roughly the same time period as Glances Backward. However, there’s very little overlap in content between the two works.

Two of the so-called “Harvard Poets” from the turn of the 20th century who are chosen for inclusion are Trumbull Stickney and George Cabot Lodge. Of the former, his academic mentor George Santayana said he was “too literary and ladylike for Harvard.” Lodge, says Gifford, was possibly not gay, but was happy to be a part of a homosocial group. Lodge died at age 36 of heart disease; one of the poems included in his posthumous collection was called “To W. W.” (i.e., Walt Whitman) and included these lines: “I toss this sheaf of song, these scattered leaves of love!/ For thee, Thy Soul and Body spent for me.”