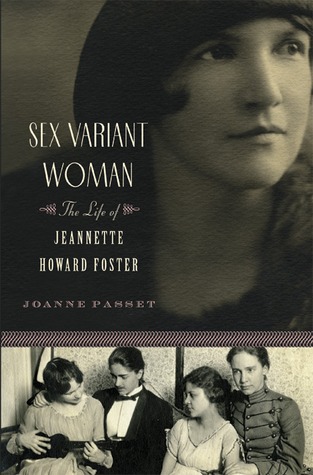

Sex Variant Woman: The Life of Jeannette Howard Foster

Sex Variant Woman: The Life of Jeannette Howard Foster

by Joanne Passet

Da Capo Press. 353 pages, $27.50

WHILE THE NAME Jeannette Howard Foster (1895–1981) may not ring an immediate bell for most readers, her life’s work, Sex Variant Women in Literature, published in 1956, was an extraordinary accomplishment for its time (thirteen years before Stonewall). Foster announced in her introduction that the purpose of her book “is to trace historically the quantity and temper of imaginative writing” about sex variant women, defined by Foster as those “who are conscious of passion for their own sex, with or without overt expression.” She covered 2,600 years of English and American literature (as well as selected European works), with plot summaries of 324 titles. Her work is not without errors and—from our standpoint today—glaring omissions; but it must be taken on its own merits as a unique work of scholarship.

The author of this biography, Joanne Passet, who teaches history at Indiana University, has chosen a traditional, chronological structure, but her obvious fascination with her subject makes for a compelling life story. Passet made use of archival material, interviewed friends and relatives, and did some close reading of Foster’s youthful poetry and mature short stories. The biography is enhanced by a number of nicely reproduced black-and-white images of friends, relatives, and residences. (An excerpt from the book appeared in this magazine’s May-June 2008 issue.)

Foster was born in Illinois in 1895 and had New England roots on both sides (four of her forebears were condemned, and two hanged, as witches in late-17th-century Salem). Her well-educated parents believed that women should attend college, but her mildly dysfunctional family life—on which Passet does not dwell unduly—assured a fairly unpleasant childhood. Even before the 20th century, she had developed her first crush—on her Sunday School teacher at the Congregational church—and throughout her life she would be in a constant turmoil of crushes, fevered but platonic friendships, casual sex partners, and long-term relationships that sometimes appeared to be more emotional than sexual. In a letter describing her almost cloistered childhood, Foster mentioned that her younger sisters had married. “So maybe something about me was ‘queer.’”

Through some lucky breaks, Foster started college at the University of Chicago. After an emotional breakdown, however, she transferred to a small Illinois school, Rockford College, which had a large number of female faculty members. It was in the college library that she discovered Havelock Ellis’ Studies in the Psychology of Sex, Volume 2 (originally published in 1901), where she found the label for what she was: “homosexual.” Her first position, teaching at a Kentucky girls’ prep school, cemented her love of the American South, and while she seems to have moved every few years throughout her life, the South remained her favorite region. There is no indication, by the way, as to her feelings about racial segregation; perhaps she had never voiced an opinion in any of her correspondence.

Distressed by the lack of intellectual curiosity of many of her students, Foster went back to school for several more degrees, including a doctorate in library science, which made her one of the first women to receive this degree. Passet, who received a doctoral degree in library science herself, reviewed Foster’s files and turned up some fascinating, and sometimes unflattering, comments by her peers: she comes off as someone who didn’t wear her scholarship lightly, was micromanaging, hypercritical, and not a team player. In Foster’s foreword to Sex Variant Women in Literature, she wrote that the “germ from which this book has grown was implanted [around World War I]when a student council voted … to dismiss two girls from a college dormitory unless they altered their habits.” The students had apparently locked themselves in a room all night, and while they were eventually placed on probation, not a word was ever plainly spoken about their crime, only “blind allusion.” Foster had been on the lookout for what might be called proto-lesbian literature virtually her entire life, having read a serialized story about a girls’ boarding school crush that appeared in a popular children’s magazine.

As a librarian, Foster had access to sources of scholarly literature and what was considered at that time sexually fraught material. She also had the tools of the trade: indexes, professional book review journals, advertisements in the backs of books, including those published by vanity presses; a reading knowledge of foreign languages; and a knack for making an educated guess and following up on it. She traveled extensively, sometimes with other women, always visiting libraries and archives. Her letters home concentrated mostly on the mundane, including her many ailments. These complaints appear to have been red herrings to deflect any suspicions about how and with whom she was enjoying herself.

A turning point came when an old girlfriend who had become a medical journal editor asked Foster to comment on an article that Alfred Kinsey had submitted for publication. By hook or by crook, she eventually found herself employed as the first librarian of the Kinsey Institute, a position that greatly aided her personal research. Better still, she began there just a few months after the publication of 1948’s Sexual Behavior in the Human Male. Foster was not favorably impressed by Kinsey’s personality, which in some ways sounds like hers: she found him controlling and headstrong. But their biggest clashes were over the purchase of books for his collection and how the library should be arranged. Because Kinsey couldn’t allow a breath of scandal, Foster knew that she would never be able to publish Sex Variant Women in Literature while in the Institute’s employ.

Passet describes Foster’s problems in getting published and her distress at having to go with Vantage, a vanity press, after plans for publication by a university press fell through. Problems cropped up later when the book was reprinted in 1976 by a women’s collective, Diana Press. The book was published again in 1985 by Naiad Press, and this is the most readily available edition today. Barbara Grier (Naiad’s founder, long-time friend of Foster, and one of Passet’s major sources) stated in her afterword to the Naiad edition that the book’s publishing history “is an example of the amount of prejudice against Lesbians and Lesbianism in our culture.”

In 1975, Foster entered a nursing home in rural Arkansas—a convenient location for friends and family, though it was virtually impossible to be an out lesbian—where she slowly declined, dying in 1981. She was fortunate in her last years to have been well aware of the lesbian movement and literature, having met or corresponded with many prominent lesbian writers and thinkers.