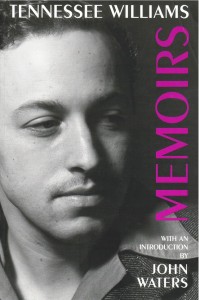

TENNESSEE WILLIAMS DIED just when AIDS was starting to explode (1983)—eight years after his Memoirs were published (1975), to more than one hostile review from a critic offended by the frank sexuality of the text. ( “If he has not exactly opened his heart,” went one notice, “he has opened his fly.”) Now New Directions is republishing them with an introduction by John Waters and an afterword by Allean Heale.

Parts of the memoirs occur during the New York run of Williams’ play Small Craft Warnings—a production whose life he extended by acting in it.

Yet the real joke in these very funny memoirs—something he knew would annoy his critics—is that he talks about everything but his vocation. He’s too cagey, too superstitious, too worried that “the shadow of the hawk’s wing” may fall on whatever element of the unconscious it is that creates his plays. “Of course,” he says, “I could devote this whole book to a discussion of the art of drama, but wouldn’t that be a bore?” Later, he is serious: “Why do I resist writing about my plays? The truth is that my plays have been the most important element of my life for God knows how many years. But I feel the plays speak for themselves. And that my life hasn’t and that it has been remarkable enough, in its continual contest with madness, to be worth setting upon paper. And my habits of work are so much more private than my daily and nightly existence.”

There you have the real perversity of this autobiography: about everything other than his writing, he’s as confessional as Casanova. (“Sexuality is an emanation, as much in the human being as the animal. Animals have seasons for it. But for me it was a round-the-calendar thing.”) These memoirs are a blur of booze, pills, boyfriends, travel, and sex. Lots of sex. “I am sorry,” he writes, “that so much of this ‘thing’ must be devoted to my amatory activities, but I was late coming out, and when I did it was with one hell of a bang.” His first tryst with Frank Merlo, the handsome Sicilian-American who became his lover for fourteen years and who created the most stable home Williams was ever to know, occasions still another apology: “I don’t want to overload this thing with homophile erotica, but let’s say that it was a fantastic hour in the dunes for me that evening even though I have never regarded sand as an ideal or even desirable surface on which to worship the little god. However, the little god was given such devout service that he must still be smiling.”

So was Williams as he wrote those words, surely. Some desire to épater le bourgeoisie—or, to cite the title of one of Gore Vidal’s essays about Williams, to “laugh at the squares”—surely lies beneath this passage, and many like it, in his memoirs. It is a laughter that culminates, perhaps, while he’s dining in Hollywood and the studio head Jack Warner turns to Frank Merlo and asks, “And what do you do, young man?” and Merlo replies, “I sleep with Mister Williams.”

As for the relationship between homosexuality and art: “I also feel that an artist’s sexual predilections or deviations are not usually pertinent to the value of his work. Of interest, certainly. Only a homosexual could have written Remembrance of Things Past.” But: “There is no doubt in my mind that there is more sensibility—which is equivalent to more talent—among the ‘gays’ of both sexes than among the ‘norms.’ (Why? They must compensate for so much.)”

But sex was never the only thing: “I have known many gays who live just for the act, that ‘rebellious hell’ persisting into middle life and later, and it is graven in their faces and even refracted from their wolfish eyes. I think what saved me from that was my first commitment being always to work. Yes, even when love did come, work was still the primary concern.” And later: “Work!!—the loveliest of all four-letter words, surpassing even the importance of love, most times.”

Williams was famous for having worked every day no matter where, no matter what. “How sad a thing,” he said after meeting Garbo, “for an artist to abandon his art. I think it’s much sadder than death.” He wrote wherever he was, not only the plays that made him probably the last great playwright this country has produced, but fiction and poetry and, just before each new play opened in New York, an essay published in the “Arts & Leisure” section of the Times that seemed designed to forestall or soften the pain that it was in the power of critics to induce in him. Writing was difficult enough: “I think writing is continually a pursuit of a very evasive quarry, and you never quite catch it.” Especially as he got older: “Is it fair not to offer to writers the same tax-exemption for depleted resources that is offered, for instance, to big oil millionaires and steel works and other corporate enterprises which own and run our country?”

From 1955 on, Williams claimed, he usually wrote with the aid of artificial stimulants. We forget how much booze writers of previous generations imbibed: Capote, Fitzgerald, Faulkner (who, Williams notes here, would go into the barn every day with a bottle of bourbon to start work). After Merlo died (of lung cancer), Williams went into a seven-year depression. Then he started going to Doctor Feelgood in New York for injections of speed. The 60’s passed in a haze of drugs and alcohol. “I was still always falling down during this time and I would always say, before falling, ‘I’m about to fall down,’ and almost nobody ever caught me.”

This theme of being alone was as crucial to him as the daily fear that he had not long to live: “Perhaps the major theme of my writings, the affliction of loneliness that follows me like my shadow, a very ponderous shadow too heavy to drag after me all of my days and nights …” In the hotel room: “Loneliness assailed me like a wolf pack with rabies, so—lacking my little red address book left in Venice—I had to consult the telephone directory for a madam I knew of, to send over a paid companion.” Yet he seems to have had people in his life till the very end, the last one a handsome Vietnam veteran in Key West (whose name we learn in the too-brief afterword, “A Few Notes and Corrections,” by Allean Hale). When, at the close of the 1960’s, his brother and mother commit Williams to a psychiatric ward in St. Louis, he asks his mother: “Why do women bring children into the world and then destroy them?” and adds, “(I still consider this a rather good question.)”

Williams’ father had part of his ear bitten off during an altercation at a poker game—an incident Williams says stopped his father from rising any higher at the shoe company where he worked. A Streetcar Named Desire was originally called “The Poker Night,” and the memoirs seem written in the cagey voice of a poker player, the give-and-take between the men playing cards in Streetcar and the women amusing themselves, a constant contest between Stanley and Blanche, his father’s honesty (the one thing Williams credits him with) and his mother’s genteel aspirations. One night he wakes up alone in his dark bedroom with this very Blanche sort of cry, “Oh, but my heart would break.” I am sure it was just a sort of Southern extravagance of statement and not a true cri de coeur: and be assured that I do not mean that “a Blanche sort of cry” isn’t or couldn’t be a true cri de coeur. … But this sounds not like me, not even me in the Victorian Suite. It lacks the humor of Blanche, and it is that humor, along with the truth, that has made Blanche a relatively imperishable creature of the stage.

The Milk Train Doesn’t Stop Here Anymore was Williams’ last Broadway premiere; after that, his new plays were mostly done Off Broadway or in cities other than New York, and they began to shrink in size, as if Williams were succumbing to the cultural evolution (death, if you like) of an art form that today boasts no playwrights as prolific, eloquent, or protean as he. By the time he chose to write the memoirs (for money, Williams said; for attention, said Gore Vidal), the culture was changing so fast that what was shocking in 1975 was not going to be shocking for much longer. Sexual liberation robbed Williams of his theme, in a way, though the new “acceptance” of homosexuality did not convince him: “Society in the Western world is presumed to have discarded its prejudices. My feeling is that the prejudices have simply gone underground.” Today, the only shocking thing in this book is Williams’ claim that the movie Jack Clayton made of The Great Gatsby was “a film that even surpassed, I think, the novel by Scott Fitzgerald.” But then, Williams says nice things about a lot of people in this book. One is never sure which to believe.

There’s a lot of gossip in the Memoirs, and glamour, and fun, but wreckage accrues as life goes on. In one of the saddest moments, during his breakup with Frank Merlo, Williams says: “Frank, I want to get my goodness back.” Though his mother, his brother, and his beloved sister Rose are all still alive when the memoirs end, Merlo is not. As for his own demise: “I hope to die in my sleep, when the time comes, and I hope it will be in the beautiful big brass bed in my New Orleans apartment, the bed which is associated with so much love and Merlo.” Instead, he choked on the plastic cap of a bottle of pills he was trying to open with his mouth —or a nasal inhaler, depending on which source you use—in his room at the Hotel Elysée, a name Williams might have made up, in Manhattan.

One can only imagine what he would have written about that—given the brilliance of his description of his near-death experiences on operating tables, and his confinement in a psychiatric hospital —just as John Waters, in his passionate fan’s introduction, wonders if Williams, had he lived longer, would have ended up an old man in a bar in Baltimore waiting for trade that never comes.

In the end, Williams remains out of anyone’s grasp. The final instance of his wily self-protection comes at the end of the book, when —like Whitman in “Crossing Brooklyn Ferry”—he addresses the reader in an uncanny way:

Do you think that I have told you my life story?

I have told you the events of my life, and described as best I could without legal repercussions, the dramatis personae of it.

But life is made up of moment-to-moment occurrences in the nerves and the perceptions, and try as you may, you can’t commit them to the actualities of your own history.

Capturing those moment-to-moment occurrences in the nerves and the perceptions was the task of art, he said. What then are the Memoirs? The first time I read them, years ago, I thought them high camp, almost like Patrick Dennis’ Little Me. This time I found the memoirs much more gritty and poignant. Williams’ autobiography is a record of almost constant flight, so that the way he died—slightly absurd, really—now seems simply frantic. “Most of you,” he writes, “belong to something that offers a stabilizing influence: a family unit, a defined social position, employment in an organization, a more secure habit of existence. I live like a gypsy, I am a fugitive. No place seems tenable to me for long anymore, not even my own skin.”

In Vidal’s review of the Memoirs, a wonderful essay called “Some Memories of the Glorious Bird and Others,” he accuses Williams of plagiarism, faulty memory, crying poor mouth, and obfuscation. ( “In the Memoirs Tennessee tells us a great deal about his sex life, which is one way of saying nothing about oneself.”) But whatever you think of these charges, the Memoirs are a comic masterpiece. There is not one dull or graceless sentence in the whole thing ( “thing” was what Williams calls his memoirs—“this thing”). Here we get his version of his own life in his own voice; and that voice was, on the page, in the theatre, a matchless style. (In Vidal’s other essay on his friend—a spirited defense called “Tennessee Williams: Someone to Laugh at the Squares With”—Williams asks Vidal to edit a story he had written, and on its return complains that Vidal had taken away his style, “which is all that I have.”) That’s what you get in these strangely inspiring memories, and that’s what probably irritated the critics. Suicide, drugs, breakdowns, institutionalization, his sister’s lobotomy, the loss of his life with Merlo, theatrical flops, even a friend’s decapitation by a subway car—all litter the book, but Williams maintains a genial equanimity that refuses to give in to self-pity ( “one of those root emotions of the human race”) or therapeutic remorse. Toward the end, Williams was considered, Vidal says, a cautionary tale: the homosexual drug casualty, the burned-out playwright. (We forget how long Williams, Vidal, and Capote were the three homosexual writers in the media, all of them great copy.) Of course, Williams’ achievement was so immense that these things did not matter. But—though Vidal thinks guilt over his homosexuality dogged Williams—in this book Williams refuses to apologize for anything.

Williams was right about his life: it is of interest. He remains today not only a playwright whose parts actors still want to perform, but a gay “bohemian” (his self-description) who both embodied and influenced an enormous cultural shift in this country . In an interview given to Mel Gussow of The New York Times on the eve of the Memoirs’ publication, Williams said that he had intended to call his story Flee, Flee, This Sad Hotel—from a poem by Anne Sexton—but on reflection decided that his life had been as much a merry tavern as a sad hotel. “My God,” he said, “I’ve gotten a lot of laughs out of life.” It’s that stance that both entertains and keeps us at a curious distance throughout the Memoirs—which, he told Gussow, he only wrote for the money ($50,000), and because he thought he’d be dead when they came out.

Andrew- Holleran’s latest novel, Grief, was published last year by Hyperion.