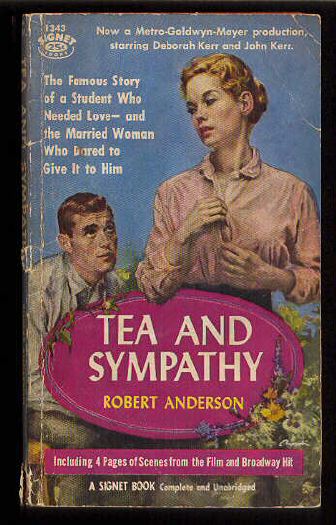

IN 1950, playwright André Gide wrote that “in the theater, homosexuality is always a false accusation, never a fact of life.” Vincente Minnelli’s film Tea and Sympathy, which opened on movie screens fifty years ago last fall, revolves around precisely such a false accusation. Rumor and innuendo destroy the reputation of a student at a boys’ boarding school; the boy’s road to redemption challenges postwar conformity, group masculinity, and smothering mothers—but never, of course, the closet. For that reason, gay critics have dismissed Tea and Sympathy in the decades since 1956. But a careful look at the circumstances of its creation and its wide-ranging cultural impact suggest that the film offered 1950’s America enough tea and sympathy to merit a reconsideration.