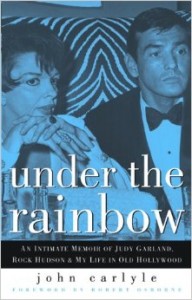

Under the Rainbow: An Intimate Memoir of Judy Garland, Rock Hudson and My Life in Old Hollywood

Under the Rainbow: An Intimate Memoir of Judy Garland, Rock Hudson and My Life in Old Hollywood

by John Carlyle

Carol & Graf. 325 pages, $26.95

“I HAVE, I admit, the old-fashioned yen to go happily to my grave with one foot in the closet,” writes pretty-boy actor John Carlyle in Under the Rainbow. Thank God he resisted the impulse. In this rescued memoir, Carlyle lifts the curtain obscuring the intersection of the movie industry, homosexuality, and mid-century Los Angeles. His beguiling book draws the reader into a detailed world of wit, sex, glamour, and tragedy. For those who love to scour Hollywood biographies for the gay parts, it’s a delicious overdose.

There’s much more here. As the book’s subtitle anticipates, Carlyle delves into the death throes of the studio system and the rise of television, but not before depicting the old West Hollywood in its charmed era as a “not overwhelmingly gay enclave” whose denizens were “hell-bent on enjoying what they could not perceive were their halcyon days.” His intimates included Noël Coward, Dorothy Parker, Lana Turner and her lesbian daughter Cheryl Crane (the two served briefly as beards for one another), and a few unsung gay men who have been crucial to the city’s development but had to fight for personal fulfillment. Carlyle’s account of Henry Willson from powerful super-agent to a paranoid has-been is one of the book’s most poignant portraits. (Willson is the man who packaged Rock Hudson, Tab Hunter, and a covey of Hollywood hunks; even after he fell from grace, many friends remained loyal to him.)That his name is largely unknown today is a testament not to his lack of talent but to the fate of untold thousands of actors who hit Hollywood with looks and dreams to face not a town made of romance but the cruel challenges of film acting—and the temptations of a city brimming with beautiful people, sex, drugs, and their inherent hazards. While he starred in nearly thirty film and TV roles from 1954 to 1991, none proved a hit; his big break, in A Star is Born with Judy Garland, was cut. That’s show biz.

But Carlyle supplies a missing piece of L.A. history. His story is that of an up-and-coming near miss whose career was clearly hobbled by the homophobia of his time. In one telling scene, Carlyle’s panicked boyfriend makes him duck to the floor of their convertible when a “name” actor (Peter Lawford) drives by.

It is a shame that Mr. Carlyle didn’t act less and write more. His sense of story and character is a constant pleasure, as are his arch phrases. On a trip to Europe, he labels the Monte Carlo casino (before the arrival of Grace Kelly) “a gilded yawn,” and later describes the public romance of gay wolf Rock Hudson and closeted lesbian Phyllis Gates as a “Louella Parsons orgasm.” But this story would have remained lost without Chris Freeman, who edited the manuscript with a deft and informed sensibility, recognized its quality, and successfully pursued its publication. Hollywood columnist Robert Osborne and actor Taylor Negron supply fore and aft commentaries based on their own friendships with the actor known as “the black star” for his dark good looks and mysterious persona. Carlyle left a rich but incomplete record; friends tell tales that he slept with James Dean and Marlon Brando, among other celluloid heroes, but he doesn’t go there. He explains: “I will try to tell the truth here, but I will draw the line at sleaze.”

The book’s central paradox is the gay leading man’s pursuit of an emotional and sexual relationship with Judy Garland during the mid-1960’s. Though he wisely avoided becoming one of Miss Garland’s many gay husbands, he felt exalted to evolve from teen fan to adult companion, though he groans over the all-night benders and frets about awakening at any moment to find her corpse next to him. For Garland fans, these previously untold stories are China White heroin. But one also recognizes a central truth Carlyle appears unable to face: he drowned his frustrations as an actor and an emotionally fragile gay man with a dependence on booze and Dexamyl, as well as obsessive social conquests of legendary film divas. Meanwhile, caring male lovers came and reluctantly left. Carlyle’s transition to Alcoholics Anonymous, a long-term gay relationship, and ultimately “controlled” drinking suggest that he was a lucky survivor; numerous other gay actor comrades committed slow suicide by alcohol or in some cases actual suicide. Carlyle himself died in 2003, in West Hollywood, at the age of 72.

____________________________________________________________________

Stuart Timmons is co-author, with Lillian Faderman, of the recently published book Gay L.A., which is reviewed in this issue.