The Art of Arno Breker

Zur Diskussion gestellt (“Put Up for Discussion”)

Schleswig-Holstein-Haus,

Schwerin, July 22–Oct. 22, 2006

NORTHERN GERMAN market towns don’t get much more idyllic and sleepy than Schwerin. All that changed this last summer when the authorities agreed to stage this, the first exhibition dedicated to Hitler’s favorite sculptor. This latter fact guaranteed there would be controversy: the exhibit’s curator Rudolf Conrades defended the show on the grounds that people deserved a chance to see the works, many of which were custom-designed for the Führer’s extensive building projects. Still, the manner of their presentation caused outrage in Germany’s artistic circles.

The fundamental connection between Breker’s career path and the Third Reich was not concealed. However, it was far from central to the account of Breker’s works. In part, this may be justified by reference to Breker’s longevity. Born in 1900, he began his artistic career in inter-war Paris, befriending figures of t

The fundamental connection between Breker’s career path and the Third Reich was not concealed. However, it was far from central to the account of Breker’s works. In part, this may be justified by reference to Breker’s longevity. Born in 1900, he began his artistic career in inter-war Paris, befriending figures of t he “late décadence” such as Jean Cocteau, who was a lifelong ally (and whose reputation has likewise been tainted by allegations of collaboration during the occupation of France). Conrades makes the point that the undoubtedly heterosexual Breker exposed himself to the æsthetic demimonde—populated by Jews, homosexuals, a wide racial mix, and so on—which contradicts the idea that he was fundamentally sympathetic to Nazism’s social politics, and in particular the Holocaust. The difficulty with this reading of his youth is that Breker not only survived the implicit damage to his career wrought by his closeness to Hitler—he died in 1991—but he also lived long enough to see the resurgence in right-wing groups in the 1980’s, and associated himself and his artistic legacy with them.

he “late décadence” such as Jean Cocteau, who was a lifelong ally (and whose reputation has likewise been tainted by allegations of collaboration during the occupation of France). Conrades makes the point that the undoubtedly heterosexual Breker exposed himself to the æsthetic demimonde—populated by Jews, homosexuals, a wide racial mix, and so on—which contradicts the idea that he was fundamentally sympathetic to Nazism’s social politics, and in particular the Holocaust. The difficulty with this reading of his youth is that Breker not only survived the implicit damage to his career wrought by his closeness to Hitler—he died in 1991—but he also lived long enough to see the resurgence in right-wing groups in the 1980’s, and associated himself and his artistic legacy with them.

For gay spectators, the exhibition revealed the chilling closeness of a striking, if often crude, neo-Classical homoerotic preoccupation with Fascist lore. Even apparently innocent subjects have a habit of bringing with them unpleasant ideological significance. For example, one of Breker’s finest works, Der Verwunderte (The Wounded One, 1938–40), while apparently drawn from a photograph of an injured French cyclist, was designed to feature in an exhibition of 45 of his works in the Orangerie in Paris in 1942. Thus it effectively portrays the conquering of France by its neighbor. Cocteau attended the opening of the show, as did the French sculptor Maillol and the painters Vlaminck and Derain. The actor-playwright Sacha Guitry, inspecting Breker’s tyrannous arrangement of manliness, commented pithily: “If these statues were ever to get an erection, we’d never make it through the avenue.”

Much of what was on display in Schwerin revealed a talented if derivative sculptor—Rodin’s influence is omnipresent—who happened to be in the right place at the right time. Anyone feeling queasy about the relentless equation of political strength and male beauty might seek solace in the poignant photographs of Breker’s many masterpieces abandoned and languishing in the snow-covered Berlin streets during the harsh winter of 1945–46.

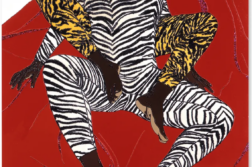

Cover art: Bereitschaft (“Readiness”; 1939). Above left: Comradeship. Above: Comrades (ca. 1930’s–early 1940’s), bas-relief sculpture. The two works on this page are undoubtedly among Breker’s most overtly homoerotic; many others depict a male and female pair in similarly heroic embrace.

Richard Canning, based in London, is author of Gay Fiction Speaks and Hear Us Out, and editor of the forthcoming gay fiction anthology Between Men (Carroll & Graf).