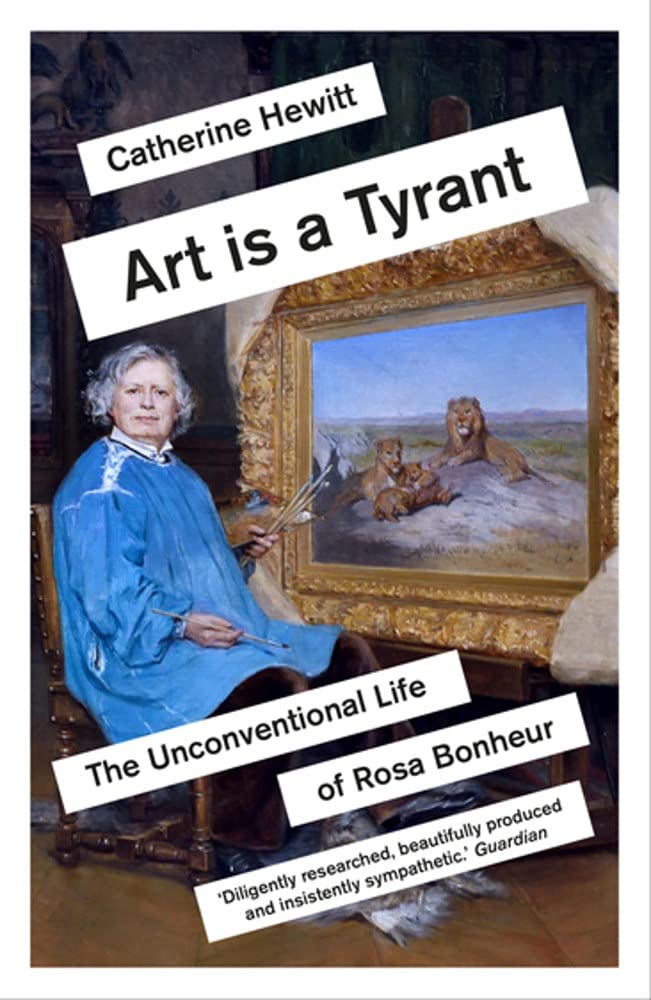

ART IS A TYRANT

ART IS A TYRANT

The Unconventional Life of Rosa Bonheur

by Catherine Hewitt

Icon Books. 483 pages, $36.59

BY THE TIME animal painter Rosa Bonheur (1822–1899) died, she had been one of the most famous and financially successful establishment artists in France for half a century. Railway tycoon Cornelius Vanderbilt had bought the canvas regarded as her masterpiece, the 8’ x 16’ Horse Fair in Paris (1853), for the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Wealthy collectors on both sides of the Atlantic had regularly commissioned canvases from her.

While her fame was due mostly to the photographic precision of her art, Bonheur also intrigued some people by wearing pants while working in her studio and with the animals she kept as models on her estate outside Paris. She told her sister: “It amuses me to see how puzzled the people are” by her male attire. But she assured the mother of a friend that “it was a practical rather than a principled choice.” When summoned by Queen Victoria (a great admirer) or other dignitaries, she delighted in wearing elegant dresses.

In the 120 years since her death, museums have put most of her works in storage, and Bonheur is remembered more for her eccentricities than for her art.

Hewitt argues that Bonheur helped “normalize the figure of the female artist.” She had repeated success with large oil paintings that demonstrated “masculine” vigor. Hewitt points out that “the perceived disparity between the virility of the painting and the gender of its author was a common source of astonishment.” Bonheur convinced the establishment not just that women could paint as well as men, but that they could paint “like a man,” i.e., with the power that great painting was understood to require.

Did Bonheur challenge sexual taboos as well? For most of her adult life, she lived with Nathalie Micas, the daughter of family friends. (Micas may have been her half sister by an extramarital affair, but Hewitt does not pursue that.) “No human would ever witness what occurred between Rosa and Nathalie once their door had been pushed closed and they were alone,” Hewitt admits at one point. (The two kept separate bedrooms, we later learn.) “The closest, most intimate love relationships can exist without sex; whether they can thrive could be debated.” We learn that Bonheur kept a diary, but not whether the artist discussed in it her relationship with Nathalie Micas.

After Micas’ death, Rosa invited a younger American artist, Anna Klumpke, to live with her and even to occupy Micas’ bedroom. Bonheur found that Klumpke, like Micas, looked like her mother, so she might have seen her as a younger sister. Hewitt claims that Bonheur cared for her new housemate “like the daughter she never had.” Readers who want to see her as a pants-wearing lesbian icon will have to do without solid proof, however.

Hewitt presents Bonheur as a proto-feminist—an “unintentional figurehead of women’s equality”—but it doesn’t appear that the artist fought for the rights of any women other than herself. The author provides no examples of subsequent women painters who found encouragement in Bonheur’s very real success. I wish she had done more to situate her subject’s art in the remarkable world of late 19th-century French painting, much of which goes unmentioned here. Did Bonheur never talk about what was going on in the Paris art world during that half-century in her diary or in her many letters? We hear that she went to painting expositions in Paris, but we never learn which ones, or what she thought of them. Even if, pace Hewitt, Bonheur didn’t “instigate a quiet revolution in the art world,” it would have made for a richer character had Hewitt highlighted the tension between her subject’s apparently conventional art and her rather unconventional life.

Richard M. Berrong, professor emeritus of French literature at Kent State University, is the author of Pierre Loti (2018) and a series of documentary films on daily life in Brittany during World War II.