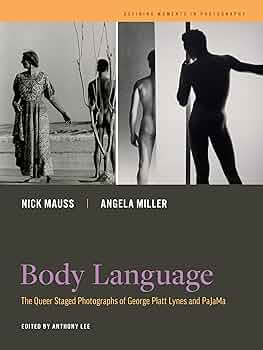

BODY LANGUAGE

BODY LANGUAGE

The Queer Staged Photographs of George Platt Lynes and PaJaMa

by Nick Mauss and Angela Miller

Univ. of California. 153 pages, $28.95

GEORGE PLATT LYNES’ 25-year career, which spanned from the late 1920s to his death in 1955, encompassed celebrity portraiture, the classical dance, women’s fashion, mythological subjects, the self-portrait, and the nude figure, especially the male nude. The first three genres identify the specifically commercial aspect of his production, otherwise known as his livelihood.

“PaJaMa” was the photography moniker for a trio of artists who painted figuratively and eschewed the tide of abstract Modernism. They included Paul Cadmus and Jared French, a couple who had been art students together in the 1920s, joined in 1937 by Margaret Hoenig, another painter who, fifteen years his senior, married Jared. Their “brand name” was a composite of their first names. They shot photographs cooperatively on the summer beaches of Provincetown, Fire Island, and Nantucket. They photographed each other, frequently joined by a changing cast of friends—often artists and usually gay, including Lynes and his intimates Monroe Wheeler and Glenway Wescott: another gay trio. PaJaMa gave out their pictures at social gatherings, treating them as “tokens of friendship … family photographs.”

Lynes was the de facto official photographer of George Balanchine’s early classical dance companies, and he knew the audience for the Ballet Russe program. Mauss reminds us that this was an era when “homosexuals” were forbidden from openly assembling in public spaces—and representation of gay bodies and behaviors were proscribed in films, on stage, “or in images circulated through the post.” Yet ballet performances remained venues for queer sociability. Mutual portrait sittings by queer photographers and other visual artists established a coterie of like sensibilities, establishing what Mauss calls a “self-elected ‘inner circle’” that, in this particular instance, at least some in-the-know would have recognized.

Lynes was the de facto official photographer of George Balanchine’s early classical dance companies, and he knew the audience for the Ballet Russe program. Mauss reminds us that this was an era when “homosexuals” were forbidden from openly assembling in public spaces—and representation of gay bodies and behaviors were proscribed in films, on stage, “or in images circulated through the post.” Yet ballet performances remained venues for queer sociability. Mutual portrait sittings by queer photographers and other visual artists established a coterie of like sensibilities, establishing what Mauss calls a “self-elected ‘inner circle’” that, in this particular instance, at least some in-the-know would have recognized.

Mauss also imparts original ideas on how Lynes distributed his work privately, focusing on his scrapbooks of sample photos. Writes Mauss: “Lynes resorted to the discreet presentational format of the album and the scrapbook to ‘exhibit’ his nudes to friends and interested parties at his home or studio.” Lynes also cut down draft proofs and sent along the newly cropped pictures as postcards. Mauss registers other artists who likewise found “novel ways” to present their work, avoiding typical “display … in galleries and museums.” Composer-photographer Max Ewing had invited guests to view the interior of his closet where he thumb-tacked from floor to ceiling a Camp potpourri of celebrities in a collection he titled “Gallery of Extraordinary Portraits.” Photographer Carl Van Vechten “projected his portraits … as slideshows in his home.” And the innovative painter and salon hostess, Florine Stettheimer, launched each new painting in her studio with a “birthday party” and invited chosen artists and critics to celebrate the “new arrival.”

Mauss’ text is dense with inquiries into Lynes’ practice, concentrating on the shifts and affiliations between his commercial modes. One such inquiry offers an examination of the photographer’s transformation of Hippolyte Flandrin’s iconic Jeune Homme nu assis au bord de la mer (1836), in which a beautiful ephebe sits nude on a rock, arms wrapped around his legs, his head resting on his knees, eyes closed. This image of solitude and male beauty has become an archetype “for the homosexual’s isolation from society.” Lynes’ 1937 studio shot Demus has a similar lone male bent over to rest his head on his knees against a backdrop of sea and sky, while seated on a modern geometric white “banquette” enclosed between rising walls painted in thick horizontal bands.

The identical studio setting is used to feature a standing female modeling a two-piece bathing suit, blankly gazed at by a trio of men gathered around her, one of whom is the Lynes stalwart, ballet star Nicholas Magallanes. In a photograph shot in 1950, Magallanes stands on a sandy studio “beach” against sunlit backdrop. He presses to him, raised off the sand, prima ballerina Tanaquil Le Clercq, crouched like Flandrin’s ephebe—this, from a sequence in the Balanchine-Jerome Robbins ballet Jones Beach. Finally, in a fourth iteration against a low horizon and sunlit sky, a male model, his back against the ground, clutches his legs to his chest and presents his nether parts to the viewer, his asshole and scrotum delineating the central “canal” between his buttocks. In Mauss’ conception, Lynes has taken a single idea—Flandrin’s jeune homme—and reimagined it in “apparently unrelated photographs spanning fashion, art, ballet, and eros.”

Angela Miller’s “PaJaMa Drama” gives us the essential terms of the trio’s practice, which began in 1937 when, said Cadmus, they would end each summer day to go out “when the light was best” and take pictures of one another using Margaret’s lightweight handheld Leica. The resulting pictures were given out at dinner parties “like playing cards.” Miller describes Paul, Jared, and Margaret as “a queer network that experimented with new forms of private life enacted in daily exchanges, and issuing in new collaborative practices.” There was no predetermined end result in their praxis, but rather it was “the act of staging and shooting the photographs” that was the point. The appearance of their bodies frozen mid-gesture gave the images the aspect of performances in medias res or stagings of tableaux vivants.

In a single evocative paragraph, Miller provides a résumé of their relationships, given that existing ties between Paul and Jared of necessity shifted after Jared’s marriage to Margaret. Yet the men’s amorous connection was not severed, and Margaret “witnessed daily the attraction between the two men.” Anxieties and accommodation moved in all directions, for Jared was pulled between commitments to both Paul and Margaret. And “Paul’s desire for Jared likewise caused emotional disruption as he was forced to witness his lover’s marriage to Margaret,” an older woman of some means who provided her husband financial support.

In a 1944 picture from Fire Island, Miller sees Margaret and Paul “in a latticework of light and shadow, a study in tense deflection. The two—both in profile—face off in a carefully composed study in symmetry. Margaret’s expression is one of strained intensity.” In another picture, “Fidelma, Margaret, and Paul,” she reads Paul’s lowered eyes as a signal of the “shaming or silencing power of Margaret’s gaze, suggesting a withering judgment on him.” Miller credits Margaret’s role as “expressed through her commanding gaze, conveying both appraisal and warning.”

But the breadth of their more than ten-year photographic meandering didn’t only focus on the fraught geometry of their emotional triangle. The summer light and the natural elements of the beach—dunes, beach grasses, uncannily torqued pieces of driftwood—became compositional elements in which friends like George Tooker, Monroe Wheeler, and Glenway Wescott coexisted with nature, sometimes nude or partially nude, sometimes draped in a toga-like tunic. The pensive figures retreat from interaction, “adding to the strange sense of suspended time that haunts these scenarios,” but their placement might be fixed near a sculptural piece of standing driftwood, and in these instances their posed stasis denies the urge to imagine a narrative. Reference to the Hellenic world of male beauty seems inescapable, but other images offer up the friends, male and female, in more contemporary gestures of relaxation, sprawled on the sand or sheltering under an umbrella for protection from the sun.

Miller’s text engages a fair amount of philosophical rumination, but pertinent to the visual examples under review. Her descriptions are usually quite on the mark, and her analyses, however speculative at times, never seem to emerge from left field. Body Language is an absorbing book for those who take photography and queer representation seriously.

Allen Ellenzweig is the author of George Platt Lynes: The Daring Eye.