NICOLAS PAGES

NICOLAS PAGES

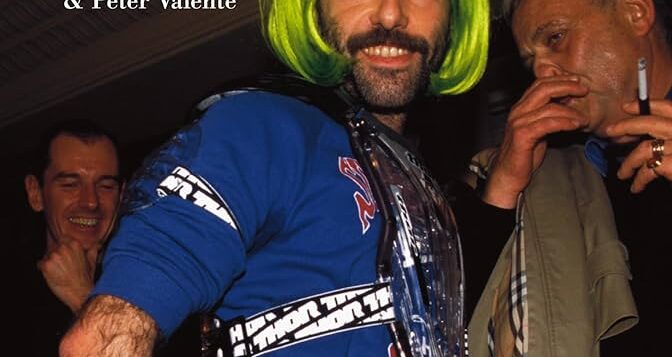

by Guillaume Dustan

Semiotext(e). 424 pages, $17.95

I’VE BEEN WATCHING Jerrod Carmichael’s new reality show Jerrod Carmichael Reality Show since it came out on HBO in early April. This is his most recent project since his 2022 comedy special Rothaniel, where he came out as gay in front of a live studio audience. The series, a personal exploration of Blackness, queerness, and strained family relationships, received an Emmy for Outstanding Writing. Carmichael’s humor is used less as a way to deflect vulnerability than as a way to underscore the awkwardness, consequence, and prevailing joy of what can only be described as unapologetic queerness.

In the first episode, Carmichael talks onscreen with one of his friends, who remains masked for the duration. His friend calls the show “masturbatorially public,” arguing that a documentary-style show, by its nature curated for an audience, is not true to life. There are shot lists, edits, framing. It might more accurately be characterized as autofiction, a genre that explores the personal with intentionality, intervention. Through autofiction, the self becomes both the narrative structure and its complication.

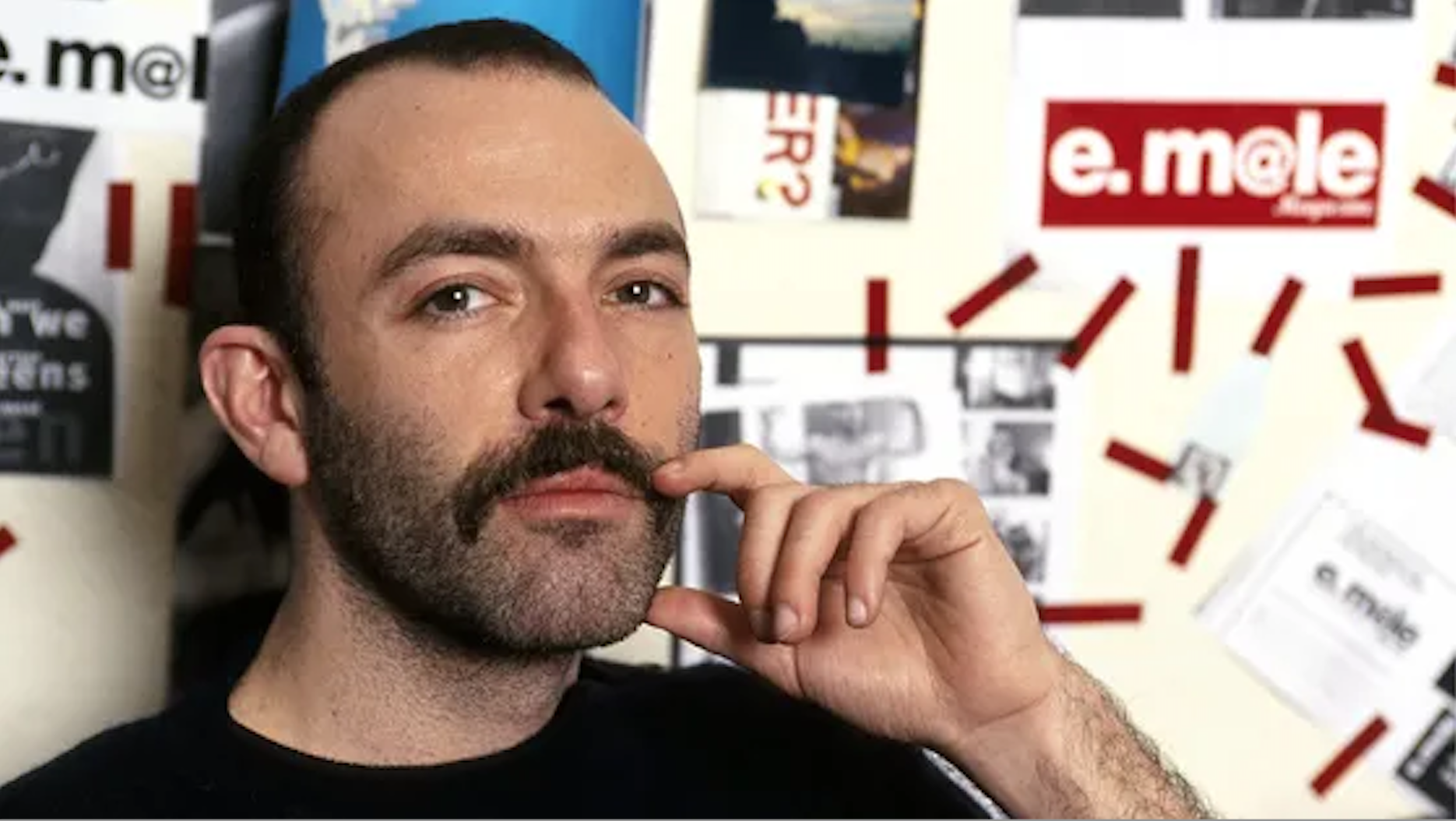

Autofiction is alive and well in Nicolas Pages, a novel by Guillaume Dustan newly translated by James Horton and Peter Valante.In an earlier essay (“A Quite Natural Desire”), he wrote: “I was pleased that everything I wrote about had actually happened. I only changed the names.” Born William Barànes in France in 1965, Dustan adopted his penname in 1995 and released three novels in the following years: In My Room (1996), a story told almost entirely from the narrator’s bedroom; I’m Going Out Tonight (1997), a long night of sexual escapades in the Parisian club and bath scene; and Stronger Than Me (1998), a reflection on the narrator’s past during the height of the AIDS epidemic in Paris.

The essay “A Quite Natural Desire” provides the framework for the recent re-release of Nicolas Pages, originally released in 1999, for which he won the Prix de Flore. The novel, recently re-released by Semiotext(e), follows Dustan’s failed romance with Swiss artist and writer Nicolas Pages, with whom he goes on a brief book tour.

Nicolas Pages is a love story told in stream-of-consciousness prose, fictional stories (“The Story of Rabbit” and “Little Bear: A Novel”), lists, and poems. Admissions like “Actually that’s not how it happened” contribute to the structureless architecture of desire that Dustan constructs, a sporadic movement characterized by a compulsive desire to act, to perform. From thoughts of sleeping with other people while in bed with his boyfriend to more self-effacing admissions of sexual prowess (“Phoneable = fuckable. My phone rings”), Dustan takes advantage of the freedom of limitless interiority that shapes autofiction. “This is the value of all the whole apparently narcissistic tendency in contemporary art,” he explains, “to take oneself as one’s subject is also to explode the stupid dichotomy between the artist and nonartist.”

In this way, Nicolas Pages is a love story made successful in its failure. The failure is in the structure, the compulsive thought that maintains its place within commas, parentheses, and fleeting thoughts characterized by their lack of punctuation. The downfall of a relationship becomes the unraveling of the self: “And then things fell apart (that is to say, improved),” Dustan writes. At the end of the book is a term glossary outlining the novel’s cast of characters and popular locales, as well as Dustan’s many aliases: “Guillaume Dustan: Me*”; “Psyggy (or Miss Psyggy): Me!”; and, later, “Fag: would take too long to explain. See also Me*.”

Dustan plays with himself, and in doing so destabilizes the relationship between fact and fiction, between desire and its complications. Nicolas Pages demonstrates how desire can manifest itself in physical and linguistic structures: run-on sentences, shopping lists, poetry, the body. The novel posits the white, gay cisgender male body as a site for experimentation. Such a focus on subjectivity amplifies Dustan’s experience without universalizing its consequences. While the genre of autofiction allows the author to evade somewhat the structural issues of privilege in race, class, and gender, Dustan plays into the genre’s narcissism by making the self, his self, a spectacle. Where Carmichael uses humor, Dustan uses punctuation (or lack thereof) both to call attention to the genre in which he is performing and to underscore the role of performance in the story of self-discovery. Nicholas Pages is about the structureless structure to which we all belong: the body.

Allison Armijo, the web editor for this magazine, is a recent graduate in creative writing from Emerson College in Boston.