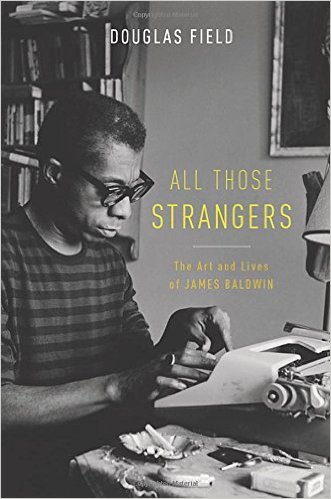

All Those Strangers: The Art

All Those Strangers: The Art

and Lives of James Baldwin

by Douglas Field

Oxford University Press

220 pages, $29.98

THIS STUDY is hard to categorize—which, given its subject, is neither surprising nor a criticism. It is definitely not a chronological biography of Baldwin; we learn little about certain periods of his life. Nor is it a text-by-text presentation or analysis of his works. Rather, it is an exploration of certain issues that played an important part in Baldwin’s life and/or works, primarily his leftist politics after World War II, racism, homosexuality, and religion. Field examines Baldwin’s ever-shifting views on these topics in both his fiction and his public pronouncements and does a good job of showing how the shifts parallel, or not, the discussions of these issues in post-World War II America. (For all the time he spent in France, Baldwin appears not to have concerned himself particularly with what French intellectuals, as opposed to American expats in Paris, were arguing at the time. As he explained in an interview: “I didn’t come to Paris in 1948, I simply left America.”)

All Those Strangers is at its best when author Douglas Field accepts Baldwin’s lack of concern for coherence and cohesion over time, and does not try to impose an artificial order where none exists. In that sense, he respects the author, who criticized America as “a country devoted to the death of the paradox,” a land that had problems dealing with individuals such as himself who were not always consistent with themselves, and saw no reason to be. This book disappoints when Field plays an English professor’s word games in an effort to reduce Baldwin’s contradictions to a single coherent system: “Baldwin’s writing demands a new kind of critical reading … one that recognizes the harmony of paradox and contradiction.” Fortunately, Field doesn’t waste much time on such empty cleverness. Instead, he devotes equal time to the several issues he treats. Homosexuality, to cut to the chase, keeps him busy showing both the complexity of Baldwin’s initial treatment of it, primarily in his fiction, and then his changing positions over time in response to successive objects of desire, both sexual and otherwise.

Baldwin first came to the attention of a large public in 1949 with the publication of his second novel, Giovanni’s Room, about a white man’s same-sex adventures in France. The lack of black characters allowed the author to sidestep issues such as black American masculinity and identity and their relationship to homosexuality, matters that would give him problems in the decades to come. The novel also established a dichotomy that would continue for most of the author’s life: he dealt with homosexuality, sometimes quite graphically, in his fiction, but seldom in his essays. When asked about the issue in interviews, he repeatedly asserted that his fiction was not about homosexuality, but love.

These assertions have not prevented gay studies faculty from using Giovanni’s Room and Baldwin’s subsequent literary works as part of an effort to construct a gay American literary canon. Nor did they prevent the leaders of the more radical Black Power movement that came into prominence in the late 1960s from dismissing Baldwin and his work as detrimental to their efforts to assert a very heterosexual and even phallic image of black (male) identity. Here Baldwin’s timing and luck were very bad. After years spent mostly in France, not overly concerned with the American civil rights movement, Baldwin returned to the U.S. in the hopes of capitalizing on his rising literary stature to become one of the movement’s central figures, only to find that the spotlight had largely been taken over by newcomers like Eldridge Cleaver and Stokely Carmichael, who were intent on excluding him because he was gay.

This is where Baldwin’s story becomes sad. Rather than retreating into the world of largely white New York leftist intellectuals among whom he had first functioned as an author, Baldwin kept trying to be accepted by a group that wanted nothing to do with him. In order to do so, as Field explains, “Baldwin’s language increasingly borrowed from the heterosexual and machismo language of the Black Power movement,” to the point that he “came dangerously close to mimicking Cleaver’s own homophobic diatribes.”

There was sad irony in the Black Panthers’ embrace of French author Jean Genet despite his flagrant homosexuality even as they derided Baldwin, who largely sold out his gay identity in an attempt to win their acceptance. But Genet was white and French and therefore did not call into question their black American masculinity. This is not a period in Baldwin’s career that’s likely to endear him to gay studies faculty who pay attention to the lives of the authors they teach.

This book isn’t light reading, though Field does largely refrain from the “lit-crit” rhetoric that makes many university press books on literature so turgid. His goal in the end is to convince more faculty to study and teach Baldwin, making a last attempt to do so by speaking of the author’s “multifaceted brilliance,” “political, moral, and cultural responsibility,” and “refusal to suffer fools or identity politics gladly.” I don’t know how many literature faculty will be won over by the second and third points, and I’m not sure that Field has sufficiently demonstrated the first. However, English professors and others not already convinced of Baldwin’s worthiness should let this book try to persuade them of it.

Richard M. Berrong, professor of French literature at Kent State, is the author of In Love with a Handsome Sailor (about Pierre Loti).