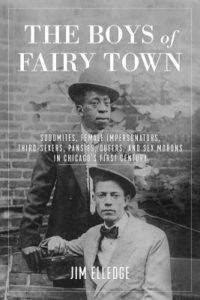

The Boys of Fairy Town: Sodomites, Female Impersonators, Third-Sexers, Pansies, Queers, and Sex Morons in Chicago’s First Century

The Boys of Fairy Town: Sodomites, Female Impersonators, Third-Sexers, Pansies, Queers, and Sex Morons in Chicago’s First Century

by Jim Elledge

Chicago Review Press. 290 pages, $30.

“THE METHOD of negro perverts who solicit men in certain Chicago cafés is usually fellatio, although pederasty by the customer is permitted,” dryly noted Dr. James G. Kiernan, Medical Superintendent of Chicago’s Cook County Hospital for the Insane, in his regular “Sexology” column for the Urologic and Cutaneous Review (1916). “Lately, as shown by recent arrests, certain cafés patronized by both negroes and whites, are the seat of male solicitation. Chicago has not developed a euphemism yet for these male perverts. In New York they are known as ‘fairies’ and wear a red necktie (inverts are generally said to prefer green). In Philadelphia they are known as ‘Brownies.’” Perhaps Kiernan feigned ignorance about Chicagoans’ terms for “homosexual” just to protect the burly reputation of his city. Maybe he wanted to insinuate that perversion was an East Coast contagion.

In 1892, Kiernan had been the first to translate the recently coined German terms “homosexual” and “heterosexual” (the latter referred to what we now call “bisexual”). Like his fellow 19th-century sexologists, he had presented “sexual perversions” as novel, rare disorders, spread from abroad, largely unknown to professionals, and hidden from the public. Yet his 1916 article exposes a homosexual underworld that was thriving in American cities by the early 20th century. Jim Elledge’s The Boys of Fairy Town brings to life this world in all its multiracial diversity from Chicago’s 1837 incorporation until the 1940s: sometimes hidden in the shadows, but often all the rage and thriving openly.

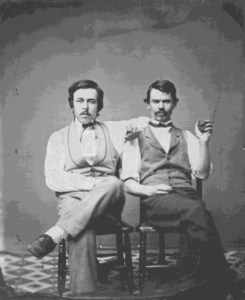

Elledge credits Kiernan with introducing the word “homosexual” in the medical realm, but notes that many other collo-quialisms were being used in medical, legal, and popular contexts: sodomite, pervert, invert, queer, pansy, and fairy. Some of the labels were used as self-identifiers, others were used as epithets by the men who were soliciting sex with men. Often there was no clear divide of sexual orientations. Even if authorities presented a clean distinction between normal and perverse, they nevertheless fretted about the unhealthy cultural mixing of the two. Elledge’s history broadly covers men who had sex with men in Chicago. He draws upon a wealth of documentation: newspaper articles, autobiographical accounts, university and Kinsey archives, census records, graduate student ethnographies from the early 20th century, and a number of existing historical works by scholars such as George Chauncey, John De Cecco, and Chad Heap. In order to make the work accessible to a general readership, Elledge resorts to an abbreviated citation system that often makes it difficult to track whether he is citing primary or secondary sources, but it keeps his narrative tight and entertaining. He does a particularly good job of highlighting the voices of otherwise nameless queer figures, not just well-documented people like Eugen Sandow (the father of bodybuilding), Henry Gerber (the founder of the first American “homophile” rights organization), or celebrated drag cabaret stars. Elledge has resurrected scores of first-person accounts of Chicago’s men-loving men. Some suffered in the closet, but many were enjoying a thrilling time in clubs, cruising grounds, and house parties all over town. His account broadly seems to have two foci: cultural life and sex. This is probably because that’s what was most documented: diaries, police reports, and newspapers all seem to dwell on the forbidden and titillating thrill of men having sex with men. The more overtly gender-transgressive (or “inverted”) people—the nellies, the nances, the fairies—were the most evident and targeted by police. However, there were many other men who had sex with men: the johns, the “sporting men,” body builders, and masculine men in all walks of life, from postal workers to politicians. Chicago’s queer life in bars and cabarets has also been meticulously documented by Chad Heap in Slumming: Sexual and Racial Encounters in American Nightlife, 1885-1940 (2009). Heap’s historical analysis of “slumming” (white upper-class hobnobbing with risqué groups) distinguishes four groups that were the object of slumming fads: new immigrants (for example, Jews and Italians), leftist bohemians, African-Americans, and queers. The lesbian and “pansy craze” of the late 1920s and ‘30s coincided with Prohibition and the Great Depression, which drew otherwise respectable people into speak- easies for alcohol and entertainment. This promiscuous blending instigated new explorations of sexuality and, as Heap argues, also prompted the sharper social distinction between hetero- and homosexuality. The commingling of high and low society and the blurring of the evolving divisions between straight and queer were out in the open at masquerade balls and some scandalous theatrical performances (notably, Mae West’s The Drag of 1927). One striking thing about Chicago, even to this day, is its social geography: it is an agglomeration of small neighborhoods distinguished (some would say segregated) by race, ethnicity, and class. There’s Greektown, Little Italy, Polish Triangle, Chinatown. The Southside became the home to many African-Americans leaving the segregated South in the Great Migration of the early 20th century. Today, the main LGBT area is Boystown, but Elledge’s work points out that there was plenty of gay action all around the city before World War II, much of it conforming to the ethnic composition of the neighborhoods. Towertown (a large area west of the Water Tower that had survived the Great Fire of 1871) would become a bohemian zone. This included arts clubs that also welcomed queers and non-queers alike for dances, lectures, masquerade balls, and debates. Some of the topics covered included the “third sex” and “Do Perverts Menace Society?” The celebrated British sexologist Havelock Ellis even mentions that “sexual inverts” could gather in the area’s churches, cafés, and clubs without fear of harassment. When Magnus Hirschfeld toured the world with his sexology lectures, he spoke to a packed house at the Dill Pickle Club in Towertown in 1931. Less highbrow entertainment was provided at other cabarets by a hermaphrodite violinist, risqué vaudevillians, and female impersonators such as Julian Eltinge (one of the highest paid actors of the 1910s). Alongside the exuberant queer culture was plenty of gay sex, which was documented in individual diaries as well as in ethnographies by several University of Chicago graduate students. Nels Anderson got to know the hobos and tramps of Chicago in the 1920s; they opened up about their survival sex and amorous exploits. Myles Vollmer, a divinity student, wrote about boy hustlers and masquerade ball antics in the 1930s. One message that comes through all of these salacious, hilarious, and poignant details is the tremendous diversity of gendered presentations and sexual behaviors that were thriving out on the streets or under the sheets in early 20th-century America (long before “queer” became an identity politics movement). The Boys of Fairy Town is also valuable for highlighting the ethnic diversity of queer Chicago (though some groups are missing, perhaps for lack of historical documentation). Large numbers of African-Americans had migrated to the South Side in the 1910s, creating an area known as Bronzeville. It too had a thriving gay community in the early 20th century, contributing to the lively jazz, masquerade, and cabaret cultures. As in Towertown, there was plenty of same-sex activity between masculine-appearing men and “she-men” who flaunted it in clubs and on the streets. Pianist and high-pitched singer George Hannah recorded one of many songs dealing with black, queer life in Bronzeville, “Freakish Man Blues,” in 1930: Call me a freakish man, what more was there Hannah also extolled lesbian life in 1930’s “The Boy in the Boat” (a euphemism for clitoris and labia): When you see two women walking hand in hand, However, it was Bronzeville’s cross-dressers and female impersonators who drew the most attention and even gained broader notoriety. “‘Gloria Swanson’ Buried in Harlem,” blared the sensational headline of the May 3, 1940, Chicago Defender (an African-American weekly). It went on to specify that it was the Sepia Gloria Swanson (née Walter Winston), an “Entertainer [who]Won Fame As A Female Impersonator.” The sympathetic obituary noted the heartbreak of Winston’s mother. The article traced Winston’s life from his birth in Atlanta in 1906, to his first break at Chicago’s Pleasure Inn, “where he soon became a favorite of cafe society. … Winston’s adaptation of witty sayings with spicy lyrics brought new faces into Pleasure’s where they would sit and sip ’til the wee hours of the morning.” The Chicago mob forced the club to move, but Winston took his act to ever more exclusive venues on the North Side before moving to clubs in Harlem. “Soon afterwards female impersonators began dotting all floor shows in New York’s nightlife”—Mae West, Joan Crawford, Clara Bow, competing Gloria Swansons—“and countless others made their bow for their share of the glory now surrounding female impersonators.” Winston seems to have died from heart disease, and his funeral was attended by over two hundred mourners who came to pay their respects to “one of the entertainment world’s most picturesque and ‘glamorous’ characters.” One gets a vivid sense of the popularity of these gay revues in the late 1920s and early ’30s. Harlem’s clubs also included women performing in male attire, like the celebrated Gladys Bentley at the Ubangi Club. Elledge’s focus is on queer male life and not what was probably an equally thriving lesbian nightlife in Chicago (although George Hannah gives us a peek). The vogue for queer acts was such that by 1930 a Variety article on “Pansy Parlors” noted with irony that despite its tough, gangster reputation, “Chicago, is going pansy. And liking it”! But their popularity also triggered a backlash. Concerns about rising syphilis rates since the 1910s had led the Chicago Vice Commission and Department of Health to crack down on prostitution and by extension the clubs that were notorious locales for female, male, and transvestite sex work. Anti-vice campaigns initially focused on white Towertown but soon targeted the “Black and Tan” mixed-race clubs of Bronzeville as well. The local African-American press astutely noted that while the police did this in the name of preventing racial conflict, to the contrary, these were places where blacks and whites could joyfully commingle. However, as Dr. Kiernan’s 1913 article suggests, miscegenation—even of the homosexual sort—was deeply troubling to white authorities. Venereal disease, prostitution, sodomy, rape, and crime in general all got blended together and distilled into the boogeyman of the “sexual psychopath” by the late 1930s, and increasingly after America’s entry into World War II. On a conceptual level, psychoanalytic theory served as a theoretical underpinning: “Certain psychiatrists regard almost all crimes as sex crimes; even theft, through its connection to the Oedipus Complex, is regarded as symbolic incest,” noted University of Chicago criminal sociologist Edwin Sutherland in 1950. But no one more stridently and forcefully persecuted queers than the closeted FBI director, J. Edgar Hoover. In an article titled “How Safe is Your Daughter?” (1947), he hysterically declared: “The most rapidly increasing type of crime is that perpetrated by degenerate sex offenders. … [It] is taking its toll at the rate of a criminal assault every 43 minutes, day and night, in the United States.” The militaristic demands of the war also justified psychiatrists’ role in establishing “homosexuality” as an official mental disorder and trying to screen out homosexuals from military service. Multiple historians have documented that, nevertheless, many gay men and lesbians enlisted and served valiantly. The Cold War that followed fueled Hoover’s anti-homosexual crusade with anti-Communist paranoia: Joseph McCarthy’s “lavender scare” to hound homosexuals out of the government. The pansy craze was over. Indeed, it seems hard to imagine it could have ever occurred, given the conservatism of the 1950s. Just as Nazism erased the hedonism of Weimar Germany, postwar America induced a prudish amnesia for its queer past. We can thank historians like Jim Elledge for bringing back to life this period of sexual and cultural vibrancy in Chicago and America. It provides a glimmer of hopefulness in our current pendulum swing to the right.

to do. …

There was a time when I was alone, my

freakish ways to see

But they’re so common now, you get one

every day in the week.

Just look ‘em over and try to understand,

They’ll go to these parties have the lights down low.

Only those parties where women can go.

You think I’m lying, just ask Tack Ann.

Took many a broad from many a man.