Hide/Seek: Difference and Desire in American Portraiture (Catalog)

Hide/Seek: Difference and Desire in American Portraiture (Catalog)

Curated by Jonathan D. Katz and David C. Ward

Smithsonian Books. 296 pages, $45.

OPENING IN WASHINGTON just days before the mid-term elections, Hide/Seek, seems like the perfect foil for right-wing demagoguery. A few images could flash red beacons in front of a Congress mired in its own bull: two self-portraits by Robert Mapplethorpe and another by Mapplethorpe of a male couple in S/M drag. Yet the show’s title hardly announces such a provocation, making the exhibit catalogue all the more crucial for understanding what’s on display. According to the back cover of this oversize, illustrated book, author Jonathan Katz is tackling nothing less than “how questions of gender and sexual identity dramatically shaped the artistic practices of influential American artists, including Thomas Eakins, Romaine Brooks, Marsden Hartley … and many more.”

Assuming the widest possible audience, Katz and co-curator David C. Ward tackle their material as social historians and as art critics. This requires weaving into the story of American portraiture a primer on the historical construction of sexual identities while also explaining artistic trends roughly from the post-Civil War era to the present. If the pictures don’t make the right-wing apoplectic, the accompanying text just might.

The catalogue begins in medias res with Katz’s introductory essay on a 1917 lithograph by George Bellows, The Shower-Bath, showing men of various ages showering, toweling off, and swimming in a male bathhouse. At the center is a young man, slender and nude, smiling back at a burly fellow who appears to be covering his tumescence with a towel. The rest of the figures are too preoccupied in their own activities to notice. As Katz observes, the print went through three editions, “testimony to its wide popularity.” The picture is clearly satirical in illustrating “a practice that everyone knew occurred and tolerated—even though it was legally proscribed.” Indeed, in the early 20th century, such approaches to effeminate men need not have betrayed a man’s sense of his masculinity. As long as he played the assertive role in any encounter, his masculinity was assured. “Within the sexual economy of Bellows’s print,” Katz writes, “queer men required straight men for erotic fulfillment and straight men valued queer men for sexual release. As a result, there was a symbiotic relationship and a form of communion … between queer and non-queer men.”

Placing such a relatively “low art” example at the center of his first discussion, Katz shows the uninitiated how queerness is constructed along lines that change according to period definitions of gender and sexual roles. And because The Shower-Bath is hardly an iconic image—unlike Bellows’ better-known paintings of prizefighters—we come to it with fresh eyes and real delight as Katz parses the visual components.

While the list of artists represented in the show encompasses the usual suspects—Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg, to name two about whom Katz has written extensively—there are also lesser lights, at least from the vantage of historical imprimatur and the high-art market. Thus, for example, an image by J. C. Leyendecker, creator of the “Arrow Shirt Man,” shows how popular commercial illustration could permit sly homoerotic content to be hidden in plain sight. More surprising are portraits of young men by two artists, Grant Wood and Andrew Wyeth, both usually associated with provincial æsthetics and the ethos of small-town rural America. In Wood’s case, Arnold Comes of Age depicts a youth staring meditatively into the middle distance while the background landscape presents a subtly homoerotic pastoral. As for Wyeth’s contribution, Katz selects a remarkably frank portrayal of a nude male youth—Wyeth’s neighbor Eric Standard, who exemplifies late hippie androgyny (long blond hair flowing in the breeze) but has a studly torso. This gender-bending portrait seems a rejection of the banner of starchy New England rectitude for which Wyeth is known.

The curatorial conundrum Katz and Ward faced in selecting artists and images must have been considerable, especially since a number of artist estates, at this late date, “objected to their inclusion.” However, Katz reminds us, Hide/Seek “features straight artists representing gay figures, gay artists representing straight figures, gay artists representing gay figures, and even straight artists representing straight figures (when of interest to gay people/culture).” By concentrating on canonical artists (even those working in “lower” arts like printmaking and photography), Hide/Seek throws down the gauntlet. It forces the cautious mercantile world of American museums, art dealers, art historians, and critics to acknowledge “the widely held but utterly unsupportable assumption that same-sex desire is at best tangential to the history of American art.”

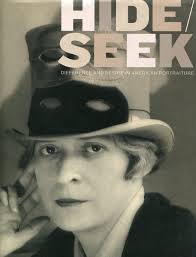

A number of iconic women artists appear as well, including Georgia O’Keefe, whose own body, ravishingly portrayed by her lover (later husband), Alfred Stieglitz, came to embody her artistic persona as much as the flower paintings and desert skulls that were her signature themes. Romaine Brooks’ emblematic self-portrait in strictly cloaked black, her eyes hidden under the brim of her hat, reveals a mysterious but potent self-possession. It joins other images of similar provenance from the Parisian expatriate lesbian coterie of the experimental 1920’s, including Berenice Abbott’s sober and stunning photograph of the poet and modernist literary figure Djuna Barnes; Brooks’ painting of Una, Lady Troubridge (Radclyffe Hall’s lover), implacable in monocle and mannish attire; and Abbott’s beautifully composed photo portrait of the Paris correspondent for The New Yorker, Janet Flanner, in costume, another American expatriate who under the pen name “Genet” masked her identity while cluing her sophisticated readership into the sexually bohemian personalities of Jazz Age Paris.

Here Katz gets to the heart of the social circumstances that enabled some gay men and lesbians in the first decades of the 20th century to finesse their sexual difference:

Whereas gender nonconformity in a man moved him down the social hierarchy, the same nonconformity in a woman could mark her ascent. … Aided and abetted by great wealth … the masculine appearance of women like Brooks and Gertrude Stein was indexed to their assumption of a masculine social role, which is to say, assuming a public, not a domestic profile. … Brooks’s paintings and Stein’s erotic love poetry are among the most openly lesbian of any artist of the period precisely because their wealth insulated them from the demands of the marketplace.

Such would not be the case in the post-war period when minority sexualities became codified in law, medicine, and psychiatry as perversions to be corrected. While the art world of the interwar years may have tentatively allowed gay artists a place, for marketing purposes the work of artists like Charles Demuth and Marsden Hartley was subsumed under the banner of “modernism,” and their same-sex references were highly coded.

The clues are masterfully teased out by Katz, but he’s forced into a shifty game of cat-and-mouse, or more appropriately hide-and-seek, when interpreting the often hermetic Cold War abstractions of Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg. Their relationship as lovers does not by itself make transparent the deployment, in Johns’ case, of well-known symbols of the everyday (targets, flags, numerals) and, in Rauschenberg’s case, imagery transferred from popular magazines and newspapers. Katz is terrific here in unearthing not only the private meanings of their work but also the dynamics of an art world that was not without its own entrenched prejudices. He writes: “Notably, when Johns and Rauschenberg were young and powerless, critics and scholars were much less reticent [sic]to maintain the silence, still routinely observed about their relationship. In a 1961 review, critic Jack Kroll, writing in ARTnews, condemned Rauschenberg’s work in such indulgently homophobic terms as to leave no doubt as to his frame of reference.” Kroll’s turns of phrase included the observation that Rauschenberg “sometimes snags his sweater” or that “weapons of the inscrutable ironist corrode gracefully with a lavender rust.”

In his densely packed and perhaps overlong introductory essay, Katz allows each artist to become the occasion for in-depth social, political, and sexual analysis. These are never uninteresting, but the earlier eras—because they are more distant from our experience—are more intriguing to decode than almost anything from the last thirty or forty years. It’s one thing to analyze visual clues to the sexuality of John Singer Sargent, Thomas Eakins, or Winslow Homer, but another to grant our relative contemporaries—artists like David Wojnarowicz, Keith Haring, or Catherine Opie—anything like the same measure of curious attention. In a large survey show such as this, the past is like a foreign country for which we need a map; for our own age, we may feel as though we can simply trust our own eyes and lived experience to feel our way to the goal.

David Ward’s contribution to the catalogue is also important. Following Katz’s illustrated text, Ward offers a series of six short essays, chronological slices that intersperse the book’s full-page plates. With titles like “Before Difference, 1870-1918” and “Stonewall and More Modern Identities,” they key the reader into eras in which visual and literary artists offered fresh reactions to constantly changing political and social circumstances. Ward integrates literary movements and figures into his discussion, beginning with Walt Whitman’s “utopian dreams … of a seamless interweaving of male affection and democratic polity,” and moving on to Hemingway and Fitzgerald and the avant-garde salons of Gertrude Stein and Carl Van Vechten. He discusses with special acuity the cross-pollination between the reckless Hart Crane, poet of The Bridge, who was, at a minimum, sexually confused and alcoholic, and the more reticent and sober painter Marsden Hartley. The latter, despite acknowledging that Crane “couldn’t help disturbing the peace of others,” nevertheless painted a compelling testament to the poet in the wake of Crane’s suicide at sea. Eight Bells Folly: Memorial to Hart Crane (1933) is a striking return to the abstract “portrait” style that Hartley had used in Portrait of a German Officer, an homage to a presumed soldier-lover of his who died in the First World War. In both paintings, numbers and forms simplified to their essentials compile a series of biographical references to an honored homosexual comrade. Ward teases out the references without ever stretching them too far.

As a reference work, Hide/Seek is a worthy addition to a personal library. Images of great cultural figures like Bessie Smith, Allen Ginsberg, Frank O’Hara, and Langston Hughes mix with works by some of our most laudable artists and photographers—from F. Holland Day and George Platt Lynes to Agnes Martin and Andy Warhol. The excellent illustrations, both color and black-and-white, are richly toned and detailed, to the extent that we can see the weave of canvas in a female nude by Agnes Martin and the drips and brushstrokes in Jasper Johns’ Souvenir. To have a book that surveys the breadth of queer influence in American visual arts, beautifully illustrated and discussed at a high level without succumbing to the worst art world jargon, is an event to be celebrated.

Allen Ellenzweig is a longtime contributor to this magazine and writes a blog at: GAPS: GayArtPolitics+Society.