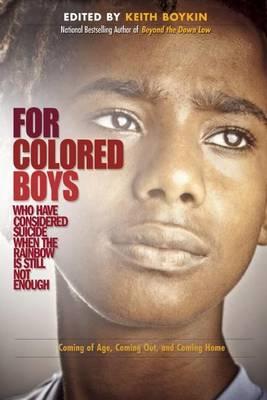

For Colored Boys Who Have Considered Suicide When the Rainbow is Still Not Enough: Coming of Age, Coming Out, and Coming Home

For Colored Boys Who Have Considered Suicide When the Rainbow is Still Not Enough: Coming of Age, Coming Out, and Coming Home

Edited by Keith Boykin

Magnus Books. 334 pages, $15.95

AS A YOUNG BOY, I used to hang out with the girls at school—long before hanging out with girls was something boys were supposed to want to do. I remember the day when the girls I played with at every recess turned on me and teased me, calling me a sissy. It was only one day, but it was humiliating and it hurt.

There would be other little episodes peculiar to a shy suburban black boy whose inclinations sometimes veered to the effeminate. Many of those memories came flooding back as I read editor Keith Boykin’s stirring collection of personal essays by gay men of color.

I have never considered suicide. I was fortunate. I grew up in the ’70s and ’80s with a brother who loved his Barbie styling head (a nearly life-sized disembodied doll’s head whose long blond hair provided hours of amusement) as much as he loved his Star Wars models. I have an uncle who is gay and parents who were loving and accepting of whoever their boys grew up to be. We both turned out to be gay, though I wouldn’t fully acknowledge my sexual orientation until after college. It may have been our socioeconomic class, my parents’ education, the fact that we lived in an integrated community; but somehow I survived my coming of age and my coming out without the despair that haunted many of the authors in Boykin’s book, and that continues to afflict many young black gay men today.

While the mainstream gay community moves inexorably, if sluggishly, down the road to  greater political inclusion and social acceptance, many young gay men of color are on a decidedly more circuitous path, struggling instead just for self-acceptance and acceptance within their families and communities. That discrimination and anti-gay violence against gay men of color routinely go ignored by the media and the public at large further heightens their isolation and suggests that society places little value on their lives. In the brief introduction to this vital compilation, Boykin points to the fact that a disturbing series of suicides among African-American males (some as young as eleven) who were gay, or perceived to be gay, has been virtually eclipsed by the public outrage and intense media coverage of similar tragedies involving white gay men. With For Colored Boys…, Boykin sets out not only to understand why a young man would consider death his only option but also to give voice to a community disproportionately silenced by shame, economic hardship, culture, and myriad other challenges.

greater political inclusion and social acceptance, many young gay men of color are on a decidedly more circuitous path, struggling instead just for self-acceptance and acceptance within their families and communities. That discrimination and anti-gay violence against gay men of color routinely go ignored by the media and the public at large further heightens their isolation and suggests that society places little value on their lives. In the brief introduction to this vital compilation, Boykin points to the fact that a disturbing series of suicides among African-American males (some as young as eleven) who were gay, or perceived to be gay, has been virtually eclipsed by the public outrage and intense media coverage of similar tragedies involving white gay men. With For Colored Boys…, Boykin sets out not only to understand why a young man would consider death his only option but also to give voice to a community disproportionately silenced by shame, economic hardship, culture, and myriad other challenges.

The 45 authors collected in the book range in age from twenty-something to sixty-something, and include African-Americans, Latinos, and Asians. Their contributions are roughly organized by life stages, beginning with “Back to School,” Craig Washington’s reminiscences of a Saturday night spent with his cousins at the beginning of the school year. Despite Washington’s crush on a male cousin, he recalls how careful he was to keep his desires to himself—that is, until, having momentarily let down his guard, he reveals that he sometimes wishes he were a girl. The swift, violent reaction of his father, followed later by the soothing reassurances of his mother, create a troubling scenario that plays out in different versions in several of these essays.

As has been thoroughly documented, however, many African-American kids, particularly those in economically struggling communities, grow up with minimal participation from their fathers. Such was the case for Jarrett Neal [who has an article in this issue], whose essay “Guys and Dolls” tells of his sexual awakening upon inadvertently walking in on his hunky gym teacher taking a shower in the locker room. Neal cleverly parallels this encounter with his infatuation with his muscle-bound, half-naked He-Man “action figures” (a term, he rightly points out, that exposes our panic over boys playing with dolls). Neal states that in the absence of a grown man in his life, a charismatic and sexually attractive teacher and a Mattel toy were the best available substitutes to fill the void. It was these two idealized studs who taught him what it means to be a man. The author’s indulgent, steamy descriptions of his teacher’s body may wander into Harlequin Romance territory but are probably right on the money in communicating how he experienced the encounter as a boy.

Boykin moves us into darker territory with stories that address verbal and sexual abuse by family members and close family friends. Rodney Terich Leonard’s “Teaspoons of December Alabama” stands out for its candor and brutal detail as the writer describes a trip to play bingo with a trusted male friend of his mother. The man’s behavioral shift from paternal to predatory is heartbreaking and terrifying. The deftly written “A House is Not a Home,” by Rob Smith, plays with time, memory, and perspective as Smith pieces together fragments of a traumatic history of rape at the hands of his stepfather.

We are guided through young adulthood with sections addressing coming out, sexual exploration, and emotional despair. In “Coming Out in the Locker Room,” Rod McCullum interviews three athletes about their experience of coming out in the sports world. It’s a remarkably candid four-way conversation during which the athletes discuss locker room sexual politics, the tendency for many black men to overcompensate for any sign of weakness with aggressive behavior, and the parallels between sports and the black church, both of which they describe as having “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” policies. At one point, former NFL player Wade Davis presciently comments, “An out player would do so much for society.” The recent essay in Sports Illustrated (May 6) in which NBA player Jason Collins came out as gay is not in this collection but could serve as an addendum to it. “I am black. And I am gay,” Collins writes, proclaiming both his race and his sexual orientation, an implicit rejection of assumptions frequently made about blackness and maleness, and a sly acknowledgment of the complicated interconnectedness of race and sexuality.

Phill Branch’s wonderful “Chicago” manages to be laugh-out-loud funny and surprisingly poignant as he chronicles his clueless entry into the gay dating world, which begins with him naïvely answering a personal ad in the back of a local gay magazine. He agrees to take an hour’s drive to a stranger’s house in an unknown corner of the city despite being unable to fully decode his date’s ad. (“He was tall, swimmers build, and liked The Simpsons. He was a ‘blk,’ ‘btm,’ into ‘ff,’ ‘ws,’ and ‘k.’ I didn’t know what any of that meant, but I figured it couldn’t be so bad.”) What ensues is a hilariously surreal encounter with a sado-masochist that takes a dark turn.

Boykin has also included works of poetry in this collection. Tim’m West’s “Ummm… Okay” is a defiant rant to a lover charitably “accepting” the speaker’s HIV positive status. Lorenzo Herrera y Lozano’s “Poetry of the Flesh” is a prose piece that uses excerpts from his poetry to explore issues of identity, sexuality, and protest. And Boykin’s own poem “How Do You Start a Revolution?” closes the collection, leaving the reader to contemplate what action he can take not only to accept himself for who he is but also to be accepted and celebrated out in the world.

Boykin, an author, television commentator, and Harvard Law School graduate, is to be commended for assembling writers with the audacity to address issues normally shrouded in silence in communities of color (such as B. Scott’s experiences as a gender nonconformist in “Love Your Truth” or Clay Cane’s argument against the “Religious Zombies” who blindly, unquestioningly flock behind a persuasive preacher). The collection might have benefited from the inclusion of more older writers, men with the historical perspective of an era before Stonewall. Still, Boykin and his contributors have done a world of good simply by telling these stories. It certainly would have been nice to read these when I was coming up.

Hilly Hicks, Jr. is a writer living and working in Los Angeles.