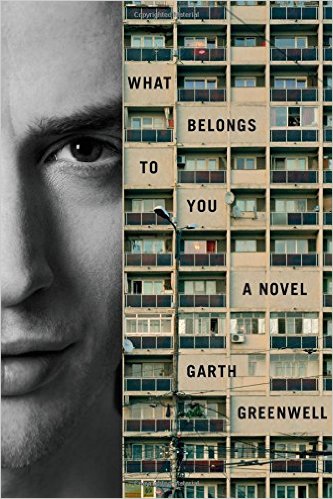

What Belongs to You

What Belongs to You

by Garth Greenwell

Farrar, Straus and Giroux

208 pages, $23.

GARTH GREENWELL is a poet and beginning novelist whose critically acclaimed novella Mitko came out in 2011. Psychologically penetrating and emotionally searing, Mitko is a taut portrait of the relationship between the book’s title character, a Bulgarian hustler, and an American college professor who teaches English at a prestigious university in the Bulgarian city of Sofia. Greenwell’s new novel, What Belongs to You, expands upon the story of Mitko. Of the book’s three parts, “Mitko,” part one, is a revised version of the original novella. Part two, “A Grave,” is an astonishing 42-page-long continuous paragraph that unravels the mystery of the narrator’s familial estrangement like an epic prose poem. Part three, “Pox,” takes the relationship between the two main characters to its inexorable conclusion.

When the book opens, the unnamed narrator and Mitko meet for the first time in a cruisy Bulgarian men’s room, where unheeded red flags set the stage for the unsparing drama that’s about to unfold:

That my first encounter with Mitko B. ended in a betrayal, even a minor one, should have given me greater warning at the time, which should in turn have made my desire for him less, if not done away with it completely. But warning, in places like the bathrooms at the National Palace of Culture, where we met, is like some element coterminous with the air, ubiquitous and inescapable, so that it becomes part of those who inhabit it, and thus part and parcel of the desire that draws us there.

As this passage illustrates, Greenwell’s style is lyrical in a way that manages to be both cerebral and visceral, a style that makes perfect sense when you consider he was an accomplished poet before trying his hand at writing fiction. When the narrator becomes sexually obsessed with Mitko, the elaborate sentences, full of psychological nuance, may remind many readers of Thomas Mann or Proust, but the book that came to my mind most often while reading What Belongs to You is The Romanian (2003), Bruce Benderson’s award-winning memoir about a similarly ill-fated relationship between an Eastern European hustler and an American journalist. Like Greenwell, Benderson realistically conveyed the heartache of unrequited love that’s inherent in these kinds of relationships, and in an elegant syntax that elevated the risqué subject matter to high art. But where Benderson’s book was laced with a mordant humor that dispelled some of the gloom, Greenwell’s book is about as bleak as it gets.

And therein lies its greatest strength and its greatest weakness: What Belongs to You is the furthest thing from escapist literature that you can possibly imagine, which means people will either love it or hate it. If you’re someone who likes to read fiction that hurts—and I mean really hurts—this one’s for you.

And there really is no end to the hurt—of unrequited attraction, of sexual exploitation and its attendant poverty, of domestic violence, homophobic parents, sexually transmitted disease, medical bureaucracy. Meanwhile, all this suffering is rendered in the most elegant sentences imaginable, sentences with a rhythm so precise, and an emotional authenticity so strong, they carry the reader along with the inevitability of a human heartbeat. Greenwell punctuates this seductive rhythm every so often with a devastating revelation, as he does in one scene in which the narrator finds himself inexplicably fascinated by a young Bulgarian boy and his grandmother, with whom he happens to be sharing a train compartment:

He made a particular gesture with his hands … a pleading gesture, and all at once and with a physical force I understood the source of my fascination with the boy, the reason I had been unable to look away. It was one of Mitko’s gestures, I realized, all of the boy’s gestures were ones I had seen Mitko use; the boy himself, his long limbs, his slenderness, the peculiar cast of his skin, might have been a small copy of the man, so that I felt I was watching Mitko as a boy, before he had become what he was now.

This jarring incident, which begins like a scene from Death in Venice and culminates in a pessimistic meditation on the possible economic future of this poor boy, highlights what is perhaps the most painful of the many heartbreaking truths the reader is forced to contend with in this remarkable debut novel that already feels like a classic. Greenwell’s descriptions of the urban blight that drives young men like Mitko into prostitution in the first place are as unsentimental and unflinching as his descriptions of the perils of getting involved with such a person. That the narrator’s own relatively meager financial resources make him powerless to change the course of Mitko’s economic future, other than to provide him with the occasional bus fare or money for penicillin, only adds to the despair.

It’s also worth mentioning that, despite being incredibly arousing at times, even Greenwell’s sex scenes are depressing, which of course is the point. It could be said that, like a sexual Sisyphus, the narrator has been tragically formatted to lust after rough trade as a Freudian consequence of his earliest sexual encounters, which were with a straight friend during adolescence. Although this isn’t the first time a gay author has written about a gay man pursuing an ostensibly straight man with unfortunate consequences, you’d be hard-pressed to find one quite as harrowing. Which isn’t meant to deter anyone from reading this beautiful book: read it and weep!

Jim Farley is an associate editor of this magazine.