Astra Pharmaceuticals, Westborough, MA.

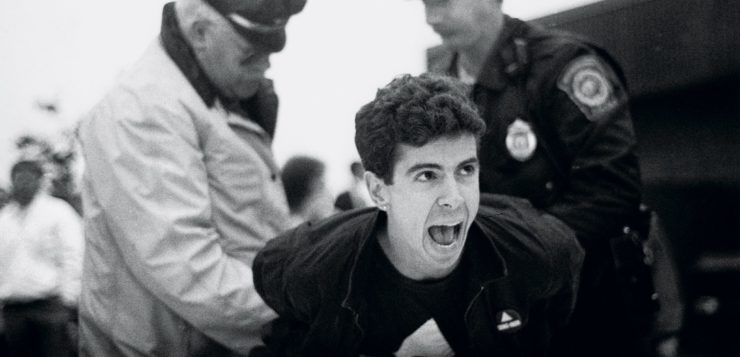

VETERAN ACTIVIST Peter Staley attained a new level of notoriety after appearing in David France’s Oscar-nominated documentary How to Survive a Plague (2012). The film follows several key members of ACT UP as they perform various acts of political theater, from occupying the headquarters of a big pharma corporation to draping a giant condom over the house of notorious homophobe Jesse Helms.

Almost ten years after that documentary was released, Staley has written a memoir that recounts his early life as a closeted party boy and stockbroker, to his first realizations that he had HIV, and later to a battle with substance abuse. Never Silent: ACT UP and My Life in Activism (Chicago Review Press) proves beyond any reasonable doubt that the personal is political, with Staley turning each of the existential challenges he faced into concrete action to bring awareness to hiv/aids at a time of corporate and government indifference. Staley offers a poignant insider’s account of the internal machinations of ACT UP as well as his later notorious ad campaign warning gay men of the dangers of crystal meth, which featured posters that read: “Huge Sale! Buy Crystal, Get HIV Free!”

Staley spoke to me by phone from his Pennsylvania home in late August. — MH

Matthew Hays: Why did you choose to write this memoir of your ACT UP days at this time?

Peter Staley: It’s been nagging at me for many years, that others tell stories about me, and there are highlight reels, but they’re never the real me. I’ve watched these things and it seems like I’m put on some sort of platform that doesn’t resonate with me. Eventually I wanted to tell my story my way. That was up against this lifetime hatred of writing. And all of it was up against fading memories. There was a feeling I had that in ten years’ time it would be a mistake-ridden book.

The real impulse was the constant response, to this day, to How To Survive a Plague. I’ve witnessed how this history can inspire people. I see it in my inbox on a weekly basis, and it’s the most beautiful part of all of this. Some of those people have gone on to become activists or doctors. They’re not momentary inspirations; they seem to have changed lives. Books have the ability to inspire, too, obviously, so it seemed the thing to do. The book and documentary will outlast me. If it can inspire, it’s worth it. It was a hard pregnancy. A two and a half year birth, in the ER, screaming. To my credit, if I’m going to do something, I don’t do it half-assed. I’m really proud of how it turned out.

MH: The book deals with various struggles you’ve faced in your life and in your activism. What was the toughest chapter to write?

PS: The addiction chapter. I saved that for the end. Working past writer’s block was tricky for me, as I just hate writing, so a strategy was to do the easy stuff first. I hadn’t spoken about that period of addiction for a long time. I was resistant from going too deep. I was honest in telling the reader that I was not going to tell a typical addict’s memoir. There’s an aisle in every bookstore for blow-by-blow accounts of addiction. And my story is no different, so I didn’t feel the need to get into everything that happened. But the activism around drug abuse felt lonelier than the ACT UP activism. To this day, it’s something I have doubts about. We got criticized for it, because people saw it as too sensational and fear-based. I am proud of it in the end. The final results are documented and real: the ads we put up were shocking, but they got people talking.

MH: There was also a huge debate around safer-sex education campaigns. Some argued that fear was a good thing to employ in ads, as it got people’s attention. Others countered that it simply led to more repression and was counterproductive. Do you think there was any benefit to fear-based campaigns?

PS: I don’t think there’s a definitive answer to that. It’s all about context. Whatever campaign you do, if you’re trying to tap into people’s emotions but fail to do so, then the campaign fails. If you look at that original, hugely expensive campaign that was run in the U.K. in the ’80s during the Thatcher years—very controversial to this day—but I continue to meet many gay men who were coming of age in Britain at the time, who say that they put their foot on the brakes because of that campaign. So the ads scared them, but also made them think. They did their job at that moment. Why didn’t Reagan do that? I will say this: I would take those ads in Britain a million times over than what we got in the U.S., which was “Nothing’s happening here! The government doesn’t care and isn’t going to say a fucking thing about this!” We may have overstepped things with the meth campaign, but our primary goal was to get gay men talking to each other about crystal meth. It’s those discussions that might change behavior.

MH: The chapter on Dallas Buyers Club blew me away. I had known that the central character it’s based on was gay, and they made him straight, but I had no idea that you had to lobby so furiously to make changes to the script.

PS: I was offended by that character being turned straight, but also by the Jared Leto character. That was probably the last great battle, or at least one of them, of straight men playing trans characters. There are major problems with the film, but I was able to convince Jean-Marc [Vallée, the director] to make many changes to the script. Originally, the script really got into this conspiracy theory that HIV doesn’t cause AIDS. I’ve been kind of a politician all my life, and I give films about AIDS out of Hollywood a kind of pass, because so few of them have been done. If they don’t really fuck it up, I’m glad they’re there. It ended up being a box office success and an Oscar success, and hopefully that will keep the door open for further AIDS projects. I’m not Sarah Schulman, and I’m not going to put the films through some theoretical shredding. If that were to happen to every film, no director would touch it again. I personally don’t like Dallas Buyers Club, but I publicly supported it. That’s a politician’s answer if ever there was one.

MH: What did you think of Sarah Schulman’s book on ACT UP, Let the Record Show?

PS: I read her book after I finished my book. I knew we would have some differences. Hopefully they will make for great companion reads. Her main messages on ACT UP are brilliant: that we were about radical democracy, and that if people within the organization wanted to do stuff, they could just do it. There was no culture in ACT UP of one group telling others what they could or couldn’t do—at least right up until the end. We have very different takes on AZT, which I didn’t see coming. I think it was more effective than it’s given credit for, which is in my book. Those are the big differences.

MH: You talk about the so-called “second silence,” when people stopped talking about AIDS for a time after the 1996 drug cocktails turned HIV into a manageable condition. What’s interesting is that this silence was broken by two films in the same year, 2012: How to Survive a Plague, which you appear in, and United in Anger, which Schulman co-produced. Yet there’s been an ongoing rivalry between these two projects, something that Sarah writes about in her book and that you touch upon in yours.

PS: I think you’re right that these two films broke the second silence. I can speak as an authority on this, and 2012 was pivotal to reinvigorating AIDS activism. That the creators of these projects have basically been at war ever since is both depressing and petty in the larger scheme of what was achieved.

MH: So many crazy activist stunts in the book, like putting Jesse Helms’ house in a condom. What was your favorite?

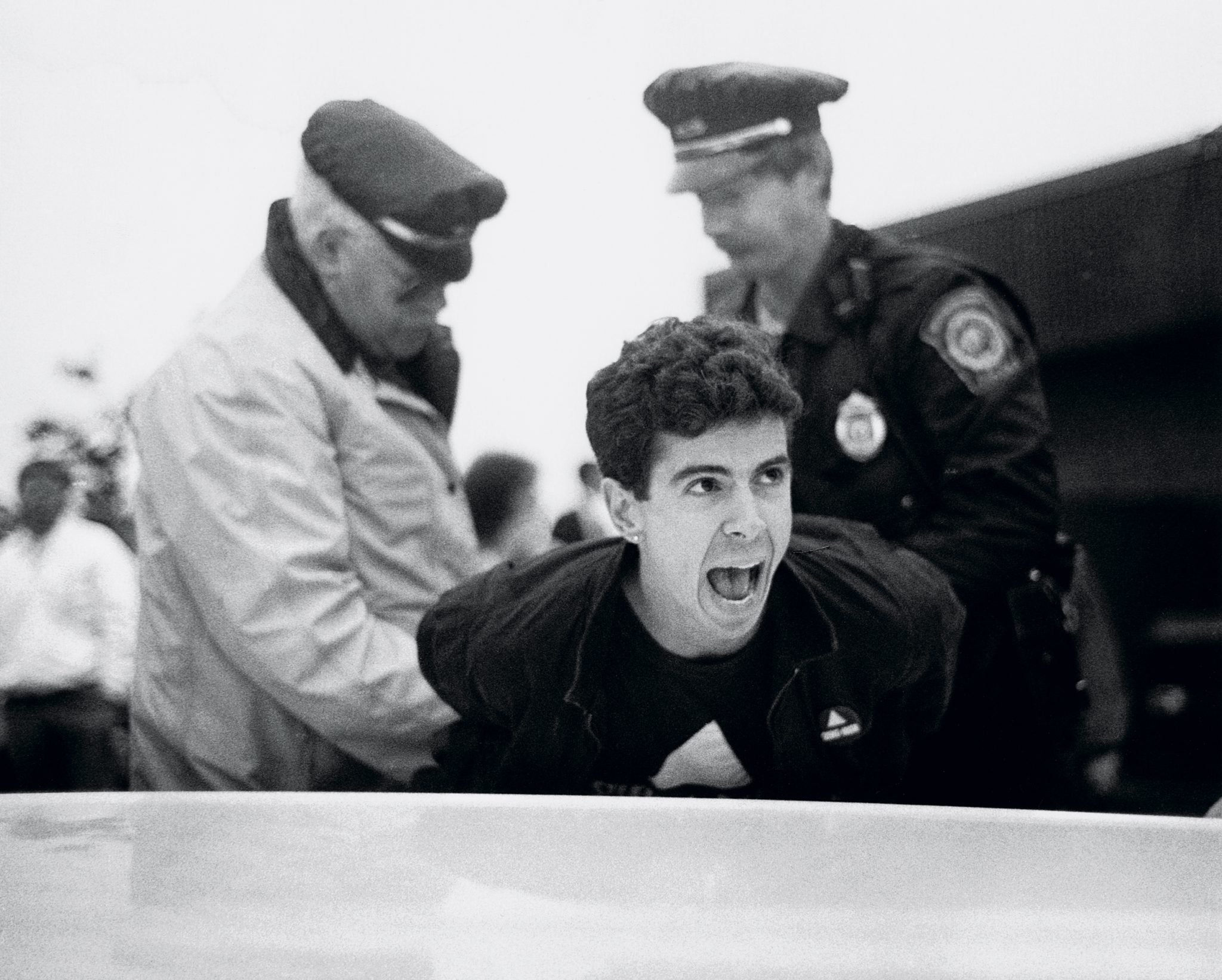

PS: Sneaking our way into the stock exchange is most emotional for me. David didn’t depict it in How to Survive a Plague, because there’s no video footage of it. It was so suspenseful, and it was great to go back and interview the activists who were on the balcony with me. We managed to pretend we were brokers and get into the exchange, and of course I had been a stock broker in my pre-activist life. It was a very complicated thing to do, and took a great deal of intricate planning.

MH: You speak about the death of your father in the book. You mention that he was a Republican all of his life, but that he didn’t flinch when you brought home a string of crazy boyfriends and that he was always supportive. Obviously, America is now extremely divided, with some saying it’s in a state of cold civil war. What is your prescription for America’s divide?

PS: It’s hard. I’m as freaked out as everyone else and as mentally stressed by everything that’s going on in America today. If AIDS hit today, and we still had the same level of homophobia as we did back then, I’m convinced that we totally would have failed. We did not have this huge lack of consensus on the basic facts of the world, the basic truths. We still lived in a world where we could agree on some things. Two years after ACT UP started, we radically shifted Gallup polling on homophobia. Gallup started asking about homosexuality, and they’d ask the same question, and they’ve been asking it since 1977: should sexual relations between people of the same sex be legal? When they asked it at the end of the decade of sexual liberation, it was evenly split. And then AIDS started, and with it a backlash. By the time ACT UP started, the throw-them-in-jail line was above sixty per cent. The it-should-be-legal line was down in the thirties. The explosion of news stories in 1985 only made it worse. As beautiful as the AIDS quilt was, it didn’t shift things.

But ACT UP really did. People could see that hundreds of us were willing to put our bodies on the line. We were the movement du jour. Every American knew who we were; we were the Black Lives Matter of our time. On a basic human level, we guilt-tripped the entire nation about our reality. Some hated us, and they were okay with us dying. ACT UP’s actions shamed these people and their attitudes. By 1989, eighty per cent of Americans said we should spend more on AIDS research. You could not do that today. You can’t get eighty per cent of Americans to agree to wear masks for Covid, or to get vaccinated. Fox News exists now. The conspiracy theories get a lot more traction now. Imagine if 45 per cent of gay men had believed the AIDS denial, the conspiracy theory that HIV didn’t cause AIDS? It would have been a slaughter—far, far worse than what we experienced.

Matthew Hays, a regular contributor to this magazine, was a member of ACT UP NY in 1988 and currently teaches media studies at Concordia University and Marianopolis College in Montreal.